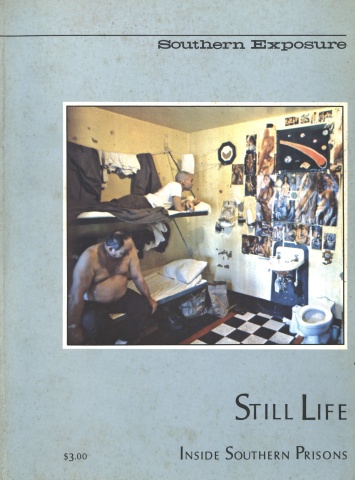

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 4, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons." Find more from that issue here.

Joe Ingle directs the Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons, a federation of prison reform organizations in 11 Southern states. A North Carolina native, Ingle confronted the problems of the criminal justice system while attending Union Theological Seminary in New York and serving his field work at the Bronx House of Detention. The experience of visiting prisoners challenged many of his assumptions about who’s guilty and dangerous in our society, and he found himself going back to the Bible. “I began rethinking the Gospel,” he recalls, “like the message of Luke 4:18 where Jesus talks about freeing the captives. The more I read, the more it seemed that a mandate on prisons was clear.”

By 1972, following Attica and a burst of media attention on conditions in the prisons, a number of Christian organizations were sponsoring prison reform programs. In Nashville, the Committee of Southern Churchmen headed by Will Campbell, focused an issue of its magazine, Katallagette, on prisons and set up the Southern Prisons Ministries. Tony Dunbar began directing that group in 1972 and Ingle joined the staff in January, 1974. Together with Michael Raff of the Mississippi Council on Human Relations and Andy Lipscomb of the Georgia CHR, they launched the Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons in 1974. Joe became director in 1977.

“Alternatives to incarceration and abolition of the death penalty are what holds us together,” explains Ingle. “We work with anyone who shares these concerns. The Coalition is a secular organization; it just happens to have a director who’s a Christian. We need the help of everybody, but personally, the only thing I have confidence in is the grace of God. We’re in the process of murdering people. Murder — another word for execution. When we realize this, maybe we’ll try to stop it.”

Joe Ingle and many others in the Southern Coalition have committed their lives to stopping state-sanctioned murder and to finding alternatives to the caging of humans. They have a lot to say about what we can do to help, individually and collectively. Bill Finger is a writer in Raleigh, NC.

Chances Are You’ll Be Angry

An individual step is crucial. It is something anyone can do and it is a direct challenge to the system as it is. You decide to walk behind the walls, to break down the isolation between the prisoner and the rest of the community; you make a visit, to see someone, to become their friend, to see what someone has to put up with inside. Once you do that, chances are you’ll be angry and you’ll want to do something more.

Visitation, of course, is not always peaches and cream. When we set up a project, we try to get a group, maybe six people, to visit six different prisoners, and we match them up. Orientation sessions are important — I remember how scared I was the first time that door shut behind me. All the fears from being socialized a certain way rushed through my whole being. “Oh, my God,” I was thinking, “what’s going to happen with ‘these people!’” Meanwhile, this guy looked up from his bunk in the first cell and said, “What are YOU doing here?” So I told him, and we sat down and talked.

Our philosophy is that ordinary citizens make the best visitors, not prison professionals. You visit somebody, support them, and try to build a friendship. That means you run into difficulty sometimes. People try to get money out of you, stuff like that. But we stress from the beginning to be up front, direct. That you’re just a friend. That circumvents a lot of problems that crop up otherwise. We have about three orientation sessions so that people will know exactly what to expect, what the prison rules are, answering any questions before visits begin.

There are so many ways that individuals have made a difference. About a year ago, a group of women who had husbands in prison came to us. They wanted to set up something called the Prison Widows Project. We helped them get it off the ground through a local Methodist church near the prison. The church became very active, getting space for the Prison Widows to operate out of, allowing people visiting their families to stay there when they needed a place to get out of the heat and get some refreshments on Saturday afternoon.

Harmon Wray and David Rainey are two people who got involved in the fight against the death penalty. Harmon is a Methodist layman in Nashville and David is a worker-priest, which means he has a full-time carpenter job and participates as a minister in Edgehill Methodist Church, a small local congregation.

After talking with us, they began a series of mailings to every pastor in the Middle Tennessee Conference of the United Methodist Church. The packet included a letter with information about the death penalty and a return coupon, where the pastor could indicate if he wanted more information, literature, a visiting speaker, or whatever. After the mailing came back, Harmon and David set up speaking engagements throughout middle Tennessee where they talk in the afternoons or evenings, sometimes adults, sometimes youth groups.

Harmon and David are good examples of how ordinary citizens can get involved — in this case, how Christians in their individual churches can contact folks in a presbytery conference, or bring the whole death penalty issue to the fore and make people deal with it.

“If You Want to Murder Us, You Murder Us”

Once you have just a few people interested, you can create a structure to work with prisoners on the outside or participate in one that’s already going. At that level, it’s very exciting — there are so many things to do.

Prison reform movements, by necessity, have to be rooted in what prisoners want done. We always try to build that presupposition into our work. After Attica, and after riots in the South, like Central Prison in Raleigh where six people were killed in 1968, the importance of organizing outside support groups became very clear to prisoners. We have focused in on the state prisons because the federal system is controlled by the federal government and there’s very little we can do about it; but we can have a great deal of impact on the state prisons. We live in the community, can go see the commissioner and get inside the prisons; we can push the bureaucracies and get things done.

The Southern states that have the most serious problems are not Mississippi and Alabama, but your more “progressive” states — Florida, North Carolina and Georgia. More people are in prison in these states. And in Georgia and Florida, large numbers are on death row. Moreover, the corrections bureaucracies are intent on expansion, and to an alarming degree, they’ve succeeded. Florida, Georgia and North Carolina are usually three of the top states in the country in terms of incarceration rates, locking up more people per capita. And the US leads the western world in per capita prison population. Florida has 17-18,000; Georgia, 14-15,000; North Carolina, around 15,000. Tennessee has 5,000; Alabama, 6,000; Misissippi has 3,000. North Carolina has 79 prisons, every one full. Mississippi has one. The common denominator is that prisoners are poor; they are predominantly black, but white or black, they are all poor. Incarceration should be a last resort, not a first response. And prisoners know that better than anybody.

In the spring of 1973, the North Carolina Prisoners Union got off the ground, an organization of individual prisoners joining together to get more freedom in dealing with the prison authorities. They voiced individual grievances, like inadequate recreation and limited access to law libraries, and they sought concrete goals — having meetings on the inside, electing governing bodies, meeting with corrections officials, circulating a newsletter.

Wayne Brooks and other key people were signing up hundreds throughout the state system. The prisoners just organized themselves. But it took outside supporters to lend it legitimacy. Rev. W. W. Finlator, a prominent Baptist pastor in Raleigh, began corresponding and visiting the leaders inside, and speaking publicly about his experiences. Wilbur Hobby, the state AFL-CIO president, sought support in the legislature. ACLU attorneys got involved, attorneys Deborah Mailman and Norman Smith providing legal counsel and an outside civil liberty base for dealing with state officials and the public. Staff from the California Prisoners Union came to North Carolina offering support and helped establish a full-time person in Raleigh, Chuck Eppinette, who coordinated the outside activities. [Editor’s note: The Supreme Court has since decided that prisoners do not have the right to associate freely without the permission of their department of corrections.]

In Tennessee, we had a similar experience. We found we were working with a lot of guys who had a long time in prison, people over twenty years. But ironically, there were no programs for them. They were just expected to sit there and rot. There were other organizations at the Tennessee State Prison for Men, like the Jaycees and Seventh Step, but no one was working with the long-timers — what one chaplain called psychosociopaths, a euphemism for people the prison administration can’t control, or are afraid of. The irony is though, that usually the people with a lot of time are the best prisoners. We thought we might be able to work with them.

We talked with the prisoners and asked, “What would you like to see happen?” They said, “We’d like to set something up just for people who have a lot of time.” So I made contact with people on the outside, local ministers, businessmen, and others, a vice-president of a prominent food distribution company, a lot of Catholics. Most of them had been touched somewhere before, in Seventh Step maybe, but not all of them. We started meeting with the Department of Corrections people. I made the initial decision not to call our organization a prisoners union, but the Lifers Club. This turned out to be crucial. We needed an aura of respectability, and you know the history of unions in the South. So we began talking about it in September, 1974, and got the thing approved, through three sets of commissioners, by June, 1975.

We started out with weekly meetings, and our outside support group would come inside every week. You couldn’t be in the Lifers Club unless you had at least a 20-year sentence. About one-third of the system statewide is lifers, probably 500 or more at the Tennessee State Prison for Men, where we started. We went out of our way to involve your hard-core convicts, people who would not kowtow to the administration, because the organization had to have respect in the eyes of the other prisoners. About 60 lifers came to the first meeting.

We got organized just in time.

On September 11, 1975, the associate warden called me up and said I better get out there. About 50 prisoners were outside of Operations, the center of the prison where all the decisions are made. They hadn’t taken over the prison, but they were not cooperating and it was a tricky and volatile situation. The warden called me up because I was one of the outside people that the prisoners would trust. I got there about 5:30 p.m. and went inside Operations.

The warden had a riot squad in full gear; he was holding a .30-.30 rifle about 20 feet from me. The prisoners were yelling at me, asking for help. They didn’t have any weapons, but there were plenty on the other side. We were talking through a screen. The prisoners just backed up against Operations, and the warden was trying to get them to go back into the cells. The mood was tense but could’ve been dealt with.

Then the warden fired his rifle into the air. When the shot went off, the prisoners called his bluff. They just said, “Okay, motherfucker, go ahead and gun us down .... If you want to murder us, you murder us. We’re not going back to those cells if you’re going to start shooting guns.” He just lost control of the situation. He pulled off his riot squad, which left the yard in the hands of the prisoners.

Then I heard some shots go off from the tower. The prisoners were asking me to come out. Here were my friends, men who I knew through the Lifers Club, asking me to go into the yard. What was I going to say? “No, I’m going to stay in Operations where it’s safe.” I figured I’d be better off in the yard because they’re less likely to shoot into a crowd of prisoners if someone from the free world is there. So I went out. For the next few hours, I was out there with the prisoners. I felt relatively safe because I was with two or three prisoners all the time. I never felt any danger from the prisoners, but I wasn’t sure what the guards were going to do. We went into the blocks with a bullhorn, trying to keep folks relatively calm. They articulated their grievances to me. We agreed on a committee who would meet with the administration, which is what we did starting around 9 or 9:30 that night. Most of the men exercising a stabilizing influence in the yard and participating in the negotiations sessions were leaders in the Lifers Club.

The tension had just built up all summer. It was like someone popped a balloon, a big release of hot air. It had started in the cafeteria. Back then, they fed the guys by unit, unit 2, 3, 4, etc. Unit 2 had been feeding last. On September 11, they ran out of meat for them, pork chops. One of the guys said, “Look, I’ve had enough. This is like the fifth time in two weeks. This isn’t fair. I want my pork chop.” “We don’t have any pork chops. We’ll bring you some bologna or something.” “Hell, I don’t want any bologna. I want my pork chop.” A guard came over. Blows were exchanged, and all hell broke loose. Somebody threw a punch first, it’s not clear who.

A lot of hot air had been let off. It was like the Day of Jubilee. We were up ’til about 5:30 in the morning in negotiations, very tense, but we finally agreed on everything. While this was going on, I found out later, Nashville’s Metro police came in and just started beating the hell out of prisoners, shooting, just completely out of hand, supposedly to “restore order.” What we had really was a police riot, not a prison riot.

Two days later, on Saturday, I came back out, saw what had happened to some of the guys. Broken arms, black and blue, blood all over the place, bullet holes in the wall. Some were seriously wounded, none were killed. Our lawyers are still representing 10 of them. After many delays, it’s coming to trial this September.

Lifers Clubs have spread to the Women’s Prison and Fort Pillow in Memphis, and we’ll soon have one at Brushy Mountain. An outside group of citizens go out there every week and meet with the guys, and we have outside meetings. We try to let the thing run itself. Our staff person’s only made a few trips to Memphis. That club’s completely held together by volunteers.

The Lifers Club has sponsored several conferences inside Women’s Prison. About 100 people from the outside have come — church women, League of Women Voters, students, legislators (we made a special effort to get them there), women and men, a real cross section. We had a top notch panel of local people. For many, it was their first experience with prisons. They were shocked to see that the women aren’t any different from anybody else.

Fighting the Death Penalty

Unlike the lifers, it’s almost impossible for people on death row to organize in any way. They’re in a maximum security situation, cut off from everything. But sometimes they can help. Earl Charles faced the death penalty for four years in Georgia, but finally his innocence was established and he got out. Now he plays a leading role with the Georgia Committee Against the Death Penalty. This past July, during the racial violence and trouble at the state prison in Reidsville, several Georgia groups working on prison reform sponsored a Human Rights for Prisoners rally in Atlanta. Earl Charles and his mother were featured speakers, and their story got out through the media coverage of the event. That’s one way people come to understand that there are innocent folks on death row who might be murdered, to hear the truth directly from one of the victims. It personalizes the whole controversy and dramatizes the need for alternatives to the present system.

Another way to fight the death penalty is organizing at the trial level. About 150 miles south of Atlanta, a stone’s throw from Plains, Georgia, is a little town called Dawson. Right in the black belt, in a county called “Terrible Terrell,” a place where the civil rights movement couldn’t make any headway — just terrible conditions and repression of any assertion from the black community.

In 1977, five kids were charged with a murder they didn’t commit. They were going to the chair. Then Millard Farmer, Scharlette Holman, Derek Alphran and volunteers from Atlanta got involved. Millard was an attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Team Defense Group, Scharlette was on our staff, and Derek was with the Georgia ACLU. They’d pack their bags and go down for days, sometimes weeks. They’d live over at Koinonia and go over to Dawson which was nearby. Next thing I knew, they’d put on a big barbecue and rally for the Dawson Five; 600- 700 folks showed up. The black community really came together and stood up and was counted. They started packing the courtroom every day. The publicity spread. The boys’ confession had been obtained at gunpoint, and this fact was made public. PBS came down and did a documentary. It was a herculean effort, but eventually the state gave up and the Dawson Five were freed. The community and the publicity beat them. The state was looking real bad.

We’re trying to bring all the resources we can to stop the death penalty at the trial level. We’re in the process of setting up what we call capital defense teams, groups of lawyers, around the South. In Kentucky, we held a conference to organize a nucleus of lawyers as backup support for attorneys assigned death penalty cases. Most lawyers have never done a death penalty case before, so they’re really at a loss to know what to do. A capital defense team provides more experience and support than a defense lawyer would usually have. Since Kentucky, we’ve had similar conferences in Memphis, where we got lawyers from Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi, and in Florida with Millard Farmer and Tony Amsterdam and other top-notch death penalty defense lawyers.

We’re also working through the political system. This past winter, two Tennessee legislators introduced a lethal injection bill. We completely opposed it because we’re opposed to any capital punishment. It’s just muddying the waters to think that there is a humane way to kill human beings. We contacted several doctors, foremost was Dr. Robert Metcalf, a respected Nashville physician in his sixties who works at Vanderbilt. We had a press conference protesting the bill at a black church in town, where Dr. Metcalf gave a speech. Then we sent a letter to every senator in the state — the bill had already blitzed through the House — in which Dr. Metcalf explained why he was opposed to lethal injection as a doctor. He talked very movingly about the Hippocratic oath and what that meant. It had a real impact, was crucial in defeating the bill. Bringing the medical profession into the fight can be crucial.

The fight against the death penalty is especially crucial in Florida, where there are 110 people on death row, more than anywhere in the country. That’s where the next execution will probably occur. We work there through the Florida Clearinghouse, trying to provide a visitor to every person who wants one. Going into that prison — that’s what makes this thing more than an issue or cause. These people become friends, people we’re talking about murdering. There are constant fund-raising events, keeping people involved, speakers going to civic clubs and schools and churches to talk about the death penalty.

We’re up against a formidable opponent there — Robert Shevin, the Florida Attorney General. Shevin is articulate, smart, a supporter of the ERA and other liberal causes. He’s also running for governor. We have the irony of feminist groups embracing Robert Shevin — who will certainly kill 100 people if he’s elected governor — because he’s for the ERA. Last April, I saw Shevin in action. John Spenkelink, who may be the first person executed since Gary Gilmore, had his appeal argued before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Tony Amsterdam, the most renowned lawyer in the country against the death penalty, represented Spenkelink. Shevin represented the State of Florida. Shevin was good, but the thing that carried through was his personal belief that John Spenkelink must be killed. His fervor was frightening. He presented John as an animal, subhuman.

John Spenkelink wants to live and he’s fighting for his life. It causes me a lot of personal grief and anguish to face the fact that a friend of mine, someone I’ve met and corresponded with for a couple years, someone I happen to care a great deal about, will probably be executed. Strapped in and murdered. Does it require that kind of ultimate sacrifice for folks to wake up to what is going on? Will they wake up, or will there be a bloodbath after the first execution? Seventy to 75 percent of the Florida people are for the death penalty. We’re organizing in all the major cities in Florida to try to slow the flood that’s going to come there in terms of human beings killed. But it’s an uphill fight.

Prisons Have a Way of Filling

We need to get away from incarceration. We use it as a first response. But it wasn’t always that way. We have to develop alternatives and be careful in the process, to be sure we don’t end up with more penitentiaries. Penitentiaries started as a reform, as an experiment. We invented them, Ben Franklin and the Quakers, and they soon spread throughout the Western world. They looked to the Middle Ages, put someone in a solitary cell and let them serve penitence, like the monks, a pure, ritual life. But instead of an experiment, we have a way of life, a custom.

In the South, departments of corrections are becoming more “professional,” which is not necessarily good. Southern corrections administrators bill themselves as humane, wanting good conditions. This usually translates into new facilities, an expanded system, and more people in it.

One of the Southern Coalition’s main goals is a moratorium on prison and jail construction. It’s hard to sell this to some of our liberal friends because they think it’s progressive to build prisons — get the convicts out of an old prison and into a new one. That’s not progressive. In 10 years, we’ll be stuck right where we were before. Only, the new prisons are bigger, hold more people, and the bureaucracy and budget get bigger. More people’s lives are controlled by a department of corrections. Prisons have a way of always filling to capacity and overfilling.

We’ve recently filed a suit in Tennessee, Trigg v. Blanton, which is a constitutional lawsuit against the state prison system, modeled on the Alabama lawsuit that Federal Judge Frank Johnson ruled on. Lawyers from the National Prison Project out of Washington, some of whom were involved in the Alabama suit, helped us. Judge Johnson ruled that prisoners in Alabama were denied their constitutional rights, that they were confined under conditions that amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. He set up his own oversight commission which resulted in a lot of changes. One major result was a total reclassification procedure where something like 80 percent of the prisoners got reclassified to a lower security status, going down from maximum to medium to minimum. That means more on work release, educational release, and outside the prisons, which is where they should be. Often a person ends up in maximum because of politics, because a warden or guard doesn’t like him, not because he’s a threat to anybody.

Besides giving relief to prisoners, we view lawsuits as an organizing vehicle, ah important education process for real prison reform. First, the media is immediately interested in lawsuits, and hence we reach the public. Then, we often run into unexpected allies. In Alabama, for example, we found ourselves working with what some folks call reactionaries, in communities where they want to put new prisons. Nobody wants new prisons in their communities. We don’t want new prisons because we got enough. So it’s an interesting alliance. We’re trying to educate the Alabama public about the enormous financial waste, the taxpayer dollars in initial construction and $10,000 a year for one prisoner — more than a year at Harvard.

And the human waste. We’re destroying prisoners, 70-75 percent go back to prison. Our penitentiary system is a failure. We have got to keep saying over and over again that there are alternatives to prison. Groups or individuals need to say it as they are in Alabama through letters to the editor, talk shows, demanding studies of the alternatives. The Scandinavian countries are very advanced in this notion. Take Holland — a very interesting example. A lot of the people running the government in Holland now were in prison camps. They know what it’s like to be in prison. And they use prison as a last resort. They use everything from educational and work programs to restitution. Minnesota is a prime example of what we should be doing here. Under their system, you keep a person in the community and work with them, reintegrating them into the community. On a purely pragmatic level, they’re saving lots of money.

But we don’t know much about alternatives in this country, and our Departments of Corrections certainly don’t want us to think about alternatives because that takes away from their business. Most prisoners — 80 percent in Tennessee — are what we call a property crime prisoner. They’ve stolen property. States are very vindictive about a property crime. In Louisiana, for example, there is an Habitual Criminal Act, which means if you commit a third felony you are eligible to be locked up for life. Now a murder is a felony but so is stealing a car. If a person is faced with three counts of stereo stealing, which is a major theft, you can get life. But if someone steals your stereo, what you want is your stereo back. You want restitution, not revenge. That’s the way we should deal with property offenders, make them repay the victim. Our present system has absolutely nothing to do with helping out the victim. Let’s help out the victim, get your stereo back. Let’s implement some restitution programs, where this person works and pays you back for your stereo.

Better yet, avoid going through the whole criminal justice system at all. What we should be doing is holding hearings, say a monthly hearing by a citizen group from a neighborhood, and deal with the offender in the community. Instead of going to court or paying a fine, you’re brought before a hearing before your peers. This is really effective in dealing with juveniles. They’re doing this in San Francisco now for juveniles. We lock up so many kids in this country for nothing, and that’s where they learn to be criminals, in juvenile training schools. For a neighborhood hearing concept to work, you have to have the cooperation of the police. And it’s in their interest to cooperate, because the police have to waste so much time in dealing with victimless crimes and also property crimes. A local ACLU chapter or League of Women Voters or church group could try to establish this system in a model neighborhood to show the legislature and the police it would work. Someone takes the time to go around and talk to the police chief and the sheriff, the mayor and the city council.

Now take your murderers. By and large — not in every case, and the bizarre cases are the ones that scare us to death in the media — a person who commits a murder has done it to someone who they know and care for. A crime of passion, a fight or some spontaneous event. A knife or gun was handy. There’s simply no reason for locking someone up for twenty years. More than likely, the murderer is rehabilitated within the first few days after the event, after he’s had a chance to realize that he’s killed somebody he’s loved. Murderers are your best prisoners and have the best record in not returning to prison. What we need to do is be sure this person won’t do it again. And that doesn’t mean you lock them up. You could leave them in the community and have them in a situation where they’re working with people and are supervised.

Corrections programs are going to succeed only when ordinary people get involved in them. Not professionals — we don’t need a bureaucratic establishment. We do need neighbors. That’s what we need and that’s what it all comes down to. Involve people in the community in the process of dealing with people who offend them. It’s the complete opposite of the philosophy of isolation and putting people behind bars. Jesus said love thy neighbor as thyself. It’s very simple. If we can begin to incorporate this on a community level and translate this through the democratic process rather than ship people off to various dungeons that we’ve constructed, I think we’re going to have a much more effective and helpful system for surviving together in this country.

Tags

Bill Finger

In 1963, the year Mississippi State faced Loyola in the NCAA, Bill Finger was playing high school basketball in Jackson. He is now a freelance writer in Raleigh, NC, and at work on a book about the players of those historic teams. (1979)

Bill Finger is a writer in Raleigh, NC. (1978)

Bill Finger is the labor editor of Southern Exposure. (1976)

Bill Finger is the Director of the Institute for Southern Studies Textiles Project. He has worked for the North Carolina AFL-CIO and the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina. (1976)