This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 4, "Generations: Women in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Twice in the history of the United States the struggle for racial equality has been midwife to a feminist movement. In the abolition movement of the 1830s and 1840s and again in the civil-rights revolt of the 1960s, women experiencing the contradictory expectations and stresses of changing roles began to move from individual discontents to a social movement in their own behalf. Working for racial justice, they developed both political skills and a belief in human rights which could justify their own claim to equality.

Moreover, in each case, the racial and sexual tensions embedded in Southern culture projected a handful of white Southern women into the forefront of those who connected one cause with the other. In the 1830s, Sarah and Angelina Grimke, devout Quakers and daughters of a Charleston slave-owning family, spoke out sharply against the moral evils of slavery and racial prejudice. “The female slaves,” they said, “are our countrywomen — they are our sisters; and to us as women, they have a right to look for sympathy with their sorrows, and effort and prayer for their rescue. . . . Women ought to feel a peculiar sympathy in the colored men’s wrong, for like him, she has been accused of mental inferiority, and denied the privileges of a liberal education.”1

Through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, religious commitment led a series of middle-class women to engage in social action, though they continued to accept many conventional attitudes about women and blacks. A new set of circumstances in the late 1950s and early ’60s, however, forced a few young Southern white women into an opposition to Southern culture more comparable to that of the Grimke sisters than to their immediate predecessors. During this period, student ministries and the YWCA fostered a growing social concern and articulated, in the language of existential theology, a radical critique of American society and Southern segregation. The ethos of the Southern civil-rights struggle perfectly matched this spirit of religious insurgency which motivated a generation of white students. When the revolt of Southern blacks began in 1960, it touched a chord of moral idealism and brought a significant group of white Southern women into a movement which would both change their lives and transform a region.

Following the first wave of sit-ins in 1960, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), at the insistence of its assistant director, Ella Baker, called a conference at Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., on Easter weekend. There black youth founded their own organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to provide a support network for direct action. SNCC set the style and tone of grass-roots organizing in the rural South and led the movement into the black belt. The spirit of adventure and commitment which animated the organization added new vitality to a deeply rooted struggle for racial equality.

In addition to this crucial role within the black movement, SNCC also created the social space within which women began to develop a new sense of their own potential. A critical vanguard of young women accumulated the tools for movement building: a language to describe oppression and justify revolt, experience in the strategy and tactics of organizing, and a beginning sense of themselves collectively as objects of discrimination.

Relative deprivation is an overused and overly clinical term to describe the joys, the pain, the anger, and the ambiguity of their experience.

Nevertheless, it was precisely the clash between the heightened sense of self-worth which the movement offered to its participants and the replication of traditional sex roles within it that gave birth to a new feminism. Treated as housewives, sex objects, nurturers, and political auxiliaries, and finally threatened with banishment from the movement, young white Southern women responded with the first articulation of the modern challenge to the sexual status quo.

The Decision

The first critical experience for most white women was simply the choice to become involved. In contrast to portions of the Northern student movement, Southern women did not join the civil-rights struggle thoughtlessly or simply as an extension of a boyfriend’s involvement. Such a decision often required a break with home and childhood friends that might never heal. It meant painful isolation and a confrontation with the possibility of violence and death. Such risks were not taken lightly. They constituted forceful acts of self-assertion.

Participation in civil rights meant beginning to see the South through the eyes of the poorest blacks, and frequently it shattered supportive ties with family and friends. Such new perceptions awakened white participants to the stark brutality of racism and the depth of their own racial attitudes. One young woman had just arrived in Albany, Georgia, when she was arrested along with the other whites in the local SNCC voter registration project. By the time she left jail after nine days of fasting, the movement was central to her life. Her father suffered a nervous breakdown. But while she was willing to compromise on where she would work, she staunchly refused to consider leaving the movement. That, it seemed to her, “would be like living death.”

For other women, such tensions were compounded by the fact that parents and friends lived in the same community. Judith Brown joined the staff of CORE and was sent to work in her home town. She wrote later of the anxieties she felt: “For that year I had to make a choice between the white community in which I had grown up and the black community, about which I knew very little.”2

Anguished parents used every weapon they could muster to stop their children. “We’ll cut off your money,” “You don’t love us,” they threatened. The women who refused to acquiesce often responded with loving determination. On June 27, 1964, a young volunteer headed for Mississippi wrote:

Dear Mom and Dad:

This letter is hard to write because I would like so much to communicate how I feel and I don’t know if I can. It is very hard to answer to your attitude that if I loved you I wouldn’t do this. ...I can only hope you have the sensitivity to understand that I can both love you very much and desire to go to Mississippi. ... There comes a time when you have to do things which your parents do not agree with.3

Even activist parents, who themselves had taken serious risks for causes they believed in, were troubled. Mimi Feingold learned years later that when she joined the freedom rides with the moral and financial support of her parents, her mother was ill with worry. Heather Tobis’ uncle wrote that her work in Mississippi compared with the struggle against fascism in the 1930s and 1940s. “We are proud to claim you as our own,” he said. But her parents asked angrily over the phone, “Do you know how much it takes to make a child?”4 Whether they kept their fears to themselves or openly opposed their children’s participation, the messages from parents, both overt and subliminal, were mixed: “We believe in what you’re doing — but don’t do it.” Their concern could only heighten their daughters’ ambivalences.

The pain of such a choice, however, was eased by the sense of purpose with which the movement was imbued. The founding statement of SNCC rang with Biblical cadences:

“. . . the philosophical or religious ideal of nonviolence (is) the foundation of our purpose, the presupposition of our faith, and the manner of our action. Nonviolence as it grows from Judaic-Christian tradition seeks a social order of justice permeated by love. . . .

“Through nonviolence, courage displaces fear; love transforms hate. Acceptance dissipates prejudice; hope ends despair. Peace dominates war; faith reconciles doubt. Mutual regard cancels enmity. Justice for all overcomes injustice. The redemptive community supersedes systems of gross immorality. ”5

The goals of the movement — described as the “redemptive community,” or more often, the “beloved community” — constituted both a vision of the future obtained through nonviolent action and a conception of the nature of the movement itself. Jane Stembridge, daughter of a Southern Baptist minister who left her studies at Union Theological Seminary to become the first paid staff member of SNCC, expressed it in these words: "...finally it all boils down to human relationship....It is the question of whether I shall go on living in isolation or whether there shall be a we. The student movement is not a cause...it is a collision between this one person and that one person. It is a lam going to sit beside you Love alone is radical.”6

Within SNCC the intensely personal nature of social action and the commitment to equality resulted in a kind of anarchic democracy and a general questioning of all the socially accepted rules. When SNCC moved into voter registration projects in the Deep South, this commitment led to a deep respect for the very poorest blacks. “Let the people decide” was about as close to an ideology as SNCC ever came. Though civil-rights workers were frustrated by the depth of fear and passivity beaten into generations of rural black people, the movement was also nourished by the beauty and courage of people who dared to face the loss of their livelihoods and possibly their lives.

One white, female civil-rights worker in Mississippi wrote that the Negroes in Holly Springs were incredibly brave, “the most real people” she had ever met. She continued, “I’m sure you can tell that the work so far has been far more gratifying than anything I ever anticipated. The sense of urgency and injustice is such that I no longer feel I have any choice . . . and every day I feel more and more of a gap between us and the rest of the world that is not engaged in trying to change this cruel system.” 7

New Realities

The movement’s vision translated into daily realities of hard work and responsibility which admitted few sexual limitations. Young white women’s sense of purpose was reinforced by the knowledge that the work they did and the responsiblities they assumed were central to the movement. In the beginning, black and white alike agreed that whites should work primarily in the white community. They had an appropriate role in urban direct-action movements where the goal was integration, but their principal job was generating support for civil rights within the white population. The handful of white women involved in the early ’60s either worked in the SNCC office —gathering news, writing pamphlets, facilitating communications —or organized campus support through such agencies as the YWCA.8

In direct-action demonstrations, many women discovered untapped reservoirs of courage. Cathy Cade attended Spelman College as an exchange student in the spring of 1962. She had been there only two days when she joined Howard Zinn in a sit-in in the black section of the Georgia Legislature. Never before had she so much as joined a picket line. Years later she testified: “To this day I am amazed. I just did it.” Though she understood the risks involved, she does not remember being afraid. Rather she was exhilarated, for with one stroke she undid much of the fear of blacks that she had developed as a high school student in Tennessee.9

Others, like Mimi Feingold, jumped eagerly at the chance to join the freedom rides but then found the experience more harrowing than they had expected. Her group had a bomb scare in Montgomery and knew that the last freedom bus in Alabama had been blown up. They never left the bus from Atlanta to Jackson, Mississippi. The arrest in Jackson was anticlimactic. Then there was a month in jail where she could hear women screaming as they were subjected to humiliating vaginal “searches.” 10

When SNCC moved into voter registration projects in the Deep South, the experiences of white women acquired a new dimension. The years of enduring the brutality of intransigent racism finally convinced SNCC to invite several hundred white students into Mississippi for the 1964 “freedom summer.” For the first time, large numbers of white women would be allowed into “the field,” to work in the rural South.

They had previously been excluded because white women in rural communities were highly visible; their presence, violating both racial and sexual taboos, often provoked repression. According to Mary King, “the start of violence in a community was often tied to the point at which white women appeared to be in the civil-rights movement.”11 However, the presence of whites also brought the attention of the national media, and, in the face of the apparent impotence of the federal law enforcement apparatus, the media became the chief weapon of the movement against violence and brutality. Thus, with considerable ambivalence, SNCC began to include whites — both men and women — in certain voter registration projects.

The freedom summer brought hundreds of Northern white women into the Southern movement. They taught in freedom schools, ran libraries, canvassed for voter registration, and endured constant harassment from the local whites. Many reached well beyond their previously assumed limits: “I was overwhelmed at the idea of setting up a library all by myself,” wrote one woman. “Then can you imagine how I felt when at Oxford, while I was learning how to drop on the ground to protect my face, my ears, and my breasts, I was asked to coordinate the libraries in the entire project’s community centers? I wanted to cry ‘HELP’ in a number of ways.”

And while they tested themselves and questioned their own courage, they also experienced poverty, oppression and discrimination in raw form. As one volunteer wrote:

For the first time in my life, I am seeing what it is like to be poor, oppressed and hated. And what I see here does not apply only to Gulfport or to Mississippi or even to the South....This summer is only the briefest beginning of this experience.12

Some women virtually ran the projects they were in. And they learned to live with an intensity of fear that they had never known before. By October, 1964, there had been 15 murders, 4 woundings, 37 churches bombed or burned, and over 1,000 arrests in Mississippi. Every project set up elaborate security precautions — regular communication by two-way radio, rules against going out at night or walking downtown in interracial groups. One woman summed up the experience of hundreds when she explained, “I learned a lot of respect for myself for having gone through all that.”13

New Role Models

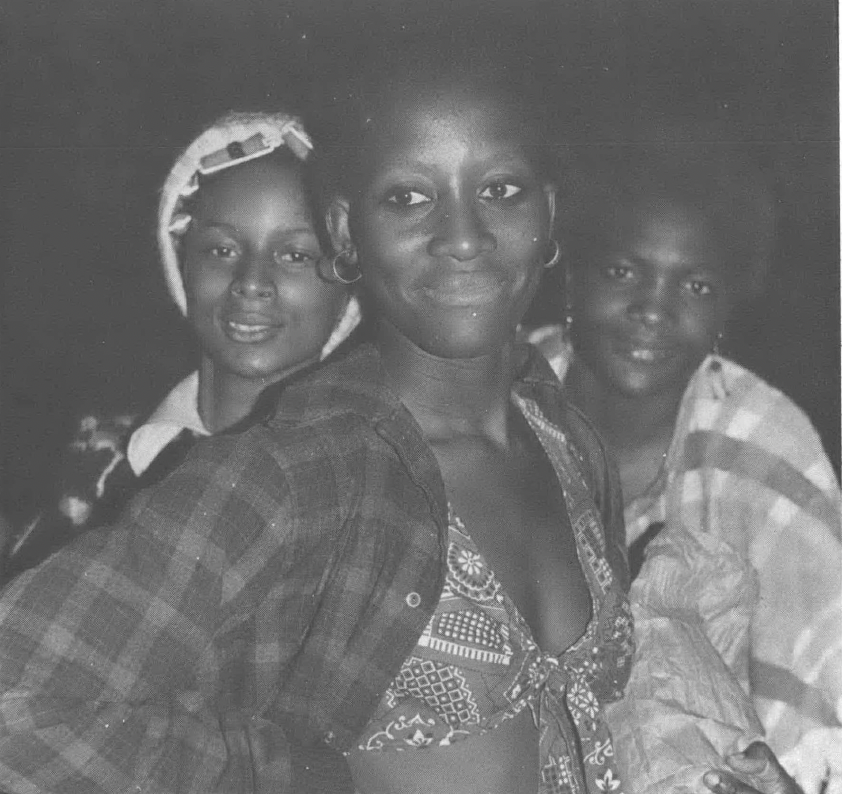

As white women tested themselves in the movement, they were constantly inspired by the examples of black women who shattered cultural images of appropriate “female” behavior. “For the first time,” according to one white Southerner, “I had role models I could respect.”14

Within the movement many of the legendary figures were black women around whom circulated stories of exemplary courage and audacity. Rarely did women expect or receive any special protection in demonstrations or jails. Frequently, direct-action teams were equally divided between women and men, on the theory that the presence of women in sit-in demonstrations might lessen the violent reaction. In 1960, slender Diane Nash had been transformed overnight from a Fisk University beauty queen to a principal leader of the direct-action movement in Nashville, Tennessee. Within SNCC she argued strenuously for direct action — sit-ins and demonstrations — over voter registration and community organization. By 1962, when she was twenty-two years old and four months pregnant, she confronted a Mississippi judge with her refusal to cooperate with the court system by appealing her two-year sentence or posting bond:

“We in the nonviolent movement have been talking about jail without bail for about two years or more. The time has come for us to mean what we say and stop posting bond. . . . This will be a black baby born in Mississippi, and thus wherever he is born he will be born in prison. I believe that if I go to jail now it may help hasten that day when my child and all children will be free — not only on the day of their birth but for all their lives. ”15

Several years later, Annie Pearl Avery awed six hundred demonstrators in Montgomery, Alabama, as a white policeman who had beaten several protesters approached her with his club raised. She reached up, grabbed his club and said, “Now what you going to do, motherfucker?”16 Stunned, the policeman stood transfixed while Avery slipped back into the crowd.

Perhaps even more important than the daring of younger activists was the towering strength of older black women. There is no doubt that women were key to organizing the black community. In 1962, SNCC staff member Charles Sherrod wrote the office that in every southwest Georgia county “there is always a ‘mama.’ She is usually a militant woman in the community, out-spoken, understanding, and willing to catch hell, having already caught her share.”

Stories of such women abound. For providing housing, food, and active support to SNCC workers, their homes were fired upon and bombed. Fannie Lou Hamer, the Sunflower County sharecropper who forfeited her livelihood to emerge as one of the most courageous and eloquent leaders of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, was only the most famous. “Mama Dolly” in Lee County, Georgia, was a seventy-year-old, grey-haired lady “who can pick more cotton, slop more pigs, plow more ground, chop more wood, and do a hundred more things better than the best farmer in the area.” For many white volunteers, they were also “mamas” in the sense of being motherfigures, new models of the meaning of womanhood.17

The Undertow of Oppression

Yet new models bumped up against old ones: self-assertion generated anxiety; new expectations existed alongside traditional ones; ideas about freedom and equality bent under assumptions about women as mere houseworkers and sexual objects. These contradictory forces finally generated a feminist response from those who could not deny the reality of their new-found strength.

Black and white women took on important administrative roles in the Atlanta SNCC office, but they also performed virtually all typing and clerical work. Very few women assumed the public roles of national leadership. In 1964, black women held a half-serious, half-joking sit-in to protest these conditions. By 1965, the situation had changed enough that a quarrel over who would take notes at staff meetings was settled by buying a tape recorder.18 In the field, there was a tendency to assume that housework around the freedom house would be performed by women. As early as 1963, Joni Rabinowitz, a white volunteer in the southwest Georgia Project, submitted a stinging series of reports on the “woman’s role.”

“Monday, 15 April:. .. The attitude around here toward keeping the house neat (as well as the general attitude toward the inferiority and ‘proper place’ of women) is disgusting and also terribly depressing. I never saw a cooperative enterprize (sic) that was less cooperative. ”

There were also ambiguities in the position of women who had been in the movement for many years and were perceived by others as important leaders. While women increasingly became a central force in SNCC between 1960 and 1965, white women were always in a somewhat anomalous position.20 New recruits saw Casey Hayden and Mary King as very powerful.21 Hayden had been an activist since the late ’50s. Her involvement in the YWCA and the Christian Faith and Life Community at the University of Texas led her to join the demonstrations which erupted in Austin in 1959. From that time on she worked full-time against segregation, sometimes through the Y, sometimes through the National Student Association or Students for a Democratic Society, but always most closely with SNCC. Mary King, daughter of a Southern Methodist minister, had visited SNCC on a trip sponsored by the Y at Ohio Wesleyan University in 1962 and soon returned to work full-time.

They and others who had joined the young movement when it included only a handful of whites knew the inner circles of SNCC through years of shared work and risk. They had an easy familiarity with the top leadership which bespoke considerable influence. Yet Hayden and King could virtually run a freedom registration program and at the same time remain outside the basic political decision-making process.22

Mary King described herself and Hayden as being in “positions of relative powerlessness.” They were powerful because they worked very hard. According to King, “If you were a hard worker and you were good, at least before 1965. . . you could definitely have an influence on policy.”23

The key phrase is “at least before 1965,” for by 1965 the positions of white women in SNCC, especially Southern women whose goals had been shaped by the vision of the “beloved community,” was in steep decline. Ultimately, a growing spirit of black nationalism, fed by the tensions of large numbers of whites, especially women, entering the movement, forced these women out of SNCC and precipitated the articulation of a new feminism.

Racial/Sexual Tensions

White women’s presence inevitably heightened the sexual tension which runs as a constant current through racist culture. Southern women understood that in the struggle against racial discrimination they were at war with their culture. They reacted to the label “Southern lady” as though it were an obscene epithet, for they had emerged from a society that used the symbol of “Southern white womanhood” to justify an insidious pattern of racial discrimination and brutal repression. They had, of necessity, to forge a new sense of self, a new definition of femininity apart from the one they had inherited. Gradually they came to understand the struggle against racism as “a key to pulling down all the... fascist notions and mythologies and institutions in the South,” including “notions about white women and repression.”24

Thus, for Southern women this tension was a key to their incipient feminism, but it also became a disruptive force within the civil-rights movement itself. The entrance of white women in large numbers into the movement could hardly have been anything but explosive. Interracial sex was the most potent social taboo in the South. And the struggle against racism brought together young, naive, sometimes insensitive, rebellious, and idealistic white women with young, angry black men, some of whom had hardly been allowed to speak to white women before. They sat-in together. If they really believed in equality, why shouldn’t they sleep together?

In many such relationships there was much warmth and caring. Several marriages resulted. One young woman described how “a whole lot of things got shared around sexuality—like black men with white women—it wasn’t just sex, it was also sharing ideas and fears, and emotional support...My sexuality for myself was confirmed by black men for the first time ever in my life, see...and I needed that very badly... It’s a positive advantage to be a big woman in the black community.”

On the other hand, there remained a dehumanizing quality in many relationships. According to one woman, it ‘‘had a lot to do with the fact that people thought they might die.” They lived their lives at an incredible pace and could not be very loving toward anybody. “So [people] would go to a staff meeting and...sleep with whoever was there.”25

Sexual relationships did not become a serious problem, however, until interracial sex became a widespread phenomenon in local communities in the summer of 1964. The same summer that opened new horizons to hundreds of women simultaneously induced serious strains within the movement itself. Accounts of what happened vary according to the perspectives of the observer.

Some paint a picture of hordes of “loose” white women coming to the South and spreading corruption wherever they went. One male black leader recounted that “where I was project director we put white women out of the project within the first three weeks because they tried to screw themselves across the city.” He agreed that black neighborhood youth tended to be sexually aggressive. “I mean you are trained to be aggressive in this country, but you are also not expected to get a positive response.”26

Others saw the initiative coming almost entirely from males. According to historian Staughton Lynd, director of the Freedom Schools, “Every black SNCC worker with perhaps a few exceptions counted it a notch on his gun to have slept with a white woman —as many as possible. And I think that was just very traumatic for the women who encountered that, who hadn’t thought that was what going South was about. ” A white woman who worked in Virginia for several years explained, “It’s much harder to say ‘No’ to the advances of a black guy because of the strong possibility of that being taken as racist.”27

Clearly the boundary between sexual freedom and sexual exploitation was a thin one. Many women consciously avoided all romantic involvements in intuitive recognition of that fact. Yet the presence of hundreds of young whites from middle- and uppermiddle- income families in a movement primarily of poor, rural blacks exacerbated latent racial and sexual tensions beyond the breaking point. The first angry response came not from the surrounding white community (which continually assumed sexual excesses far beyond the reality) but from young black women in the movement.

A black woman pointed out that white women would “do all the shit work and do it in a feminine kind of way while [black women] ...were out in the streets battling with the cops. So it did something to what [our] femininity was about. We became amazons, less than and more than women at the same time.” Another black woman added, “If white women had a problem in SNCC, it was not just a maleIwoman problem...it was also a black woman/white woman problem. It was a race problem rather than a woman’s problem.”28 And a white woman, asked whether she experienced any hostility from black women, responded, “Oh tons and tons! I was very, very afraid of black women, very afraid.” Though she admired them and was continually awed by their courage and strength, her sexual relationships with black men placed a barrier between herself and black women.29

Soon after the 1964 summer project, black women in SNCC sharply confronted male leadership. They charged that they could not develop relationships with the black men because the men did not have to be responsible to them as long as they could turn to involvement with white women.

Black women’s anger and demands constituted one part of an intricate maze of tensions and struggles that were in the process of transforming the civil-rights movement. SNCC had grown from a small band of sixteen to a swollen staff of 180, of whom 50% were white. The earlier dream of a beloved community was dead. The vision of freedom lay crushed under the weight of intransigent racism, disillusion with electoral politics and nonviolence, and differences of race, class, and culture within the movement itself. Within the rising spirit of black nationalism, the anger of black women toward white women was only one element.

It is in this context that Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, one of the most powerful black women in SNCC, is said to have written a paper on the position of women in SNCC. If a copy of this paper exists I have yet to find it. Those I have interviewed who attended the conference at which she delivered it, or who heard about it soon thereafter, have hazy and contradictory memories. Nevertheless this paper has been cited frequently in the literature of contemporary feminism as the earliest example of “women’s consciousness” within the new left.

Ruby Doris Smith Robinson was a strong woman. As a teenager she had joined the early Atlanta demonstrations during her sophomore year at Spelman College. That year, as a participant in the Rock Hill, South Carolina, sit-in she helped initiate the “jail - no bail” policy in SNCC. A month in the Rock Hill jail bound her to the movement with a zeal born of common suffering, deepened commitment, and shared vision. Soon she was a battle-scarred veteran, respected by everyone and feared by many; she ran the SNCC office with unassailable authority.

As an early leader of the black nationalist faction, Robinson hated white women for years because white women represented a cultural ideal of beauty and “femininity” which by inference defined black women as ugly and unwomanly. But she was also aware that women had from time to time to assert their rights as women. In 1964, she participated in and perhaps led the sit-in in the SNCC office protesting the relegation of women to typing and clerical work. Robinson died of cancer in 1968, and we may never know her own assessment of her feelings and intentions in 1964.30 We do know, however, that tales of her memo generated feminist echoes in the minds of many. And Stokely Carmichael’s reputed response that “the only position for women in SNCC is prone” stirred up even more. For Southern white women who had devoted several years of their lives to the vision of a beloved community, the rejection of nonviolence and movement toward a more ideological, centralized, and black nationalist movement was bitterly disillusioning. Mary King recalled, “It was very sad to see something that was so creative and so dynamic and so strong [disintegrating] ....I was terribly disappointed for a long time.... I was most affected by the way that black women turned against me. That hurt more than the guys. But it had been there, you know. You could see it coming.”31

Rebirth of Feminism

In the fall of 1965, Mary King and Casey Hayden spent several days of long discussions in the mountains of Virginia. Both of them were on their way out of the movement, though they were not fully conscious of that fact. Finally they decided to write a “kind of memo” addressed to “a number of other women in the peace and freedom movements.”32 In it they argued that women, like blacks, “seem to be caught in a common-law caste system that operates, sometimes subtly, forcing them to work around or outside hierarchical structures of power which may exclude them. Women seem to be placed in the same position of assumed subordination in personal situations too. It is a caste system which, at its worst, uses and exploits women.”

Hayden and King set the precedent of contrasting the movement’s egalitarian ideas with the replication of sex roles within it. They noted the ways in which women’s position in society determined women’s roles in the movement — like cleaning houses, doing secretarial work, and refraining from active or public leadership. At the same time, they observed, “having learned from the movement to think radically about the personal worth and abilities of people whose role in society had gone unchallenged before, a lot of women in the movement have begun trying to apply those lessons to their own relations with men. Each of us probably has her own story of the various results.”

They spoke of the pain of trying to put aside “deeply learned fears, needs, and self-perceptions...and...to replace them with concepts of people and freedom learned from the movement and organizing.” In this process many people in the movement had questioned basic institutions, such as marriage and child-rearing. Indeed, such issues had been discussed over and over again, but seriously only among women. The usual male response was laughter, and women were left feeling silly. Hayden and King lamented the “lack of community for discussion: Nobody is writing, or organizing, or talking publicly about women, in any way that reflects the problems that various women in the movement came across.” Yet despite their feelings of invisibility, their words also demonstrated the ability to take the considerable risks involved in sharp criticisms. Through the movement they had developed too much self-confidence and self-respect to accept passively subordinate roles.

The memo was addressed principally to black women — long time friends and comrades-in-nonviolent-arms — in the hope that, “perhaps we can start to talk with each other more openly than in the past and create a community of support for each other so we can deal with ourselves and others with integrity and can therefore keep working.” In some ways, it was a parting attempt to halt the metamorphosis in the civil-rights movement from nonviolence to nationalism, from beloved community to black power. It expressed Hayden and King’s pain and isolation as white women in the movement. The black women who received it were on a different historic trajectory. They would fight some of the same battles as women, but in a different context and in their own way.

This “kind of memo” represented a flowering of women’s consciousness that articulated contradictions felt most acutely by middle-class white women. While black women had been gaining strength and power within the movement, white women’s position — at the nexus of sexual and racial conflicts — had become increasingly precarious. Their feminist response, then, was precipitated by loss in the immediate situation, but it was a sense of loss against the even deeper background of new strength and self-worth which the movement had allowed them to develop. Like their foremothers in the nineteenth century, they confronted this dilemma with the tools which the movement had given them: a language to name and describe oppression; a deep belief in freedom, equality and community soon to be translated into “sisterhood”; a willingness to question and challenge any social institution which failed to meet human needs; and the ability to organize.

It is not surprising that the issues were defined and confronted first by Southern women whose consciousness developed in a context which inextricably and paradoxically linked the fate of women and black people. These spiritual daughters of Sarah and Angelina Grimke kept their expectations low in November, 1965. “Objectively,” Hayden and King wrote, “the chances seem nil that we could start a movement based on anything as distant to general American thought as a sex-caste system.”32 But change was in the air and youth was on the march.

In the North there were hundreds of women who had shared in the Southern experience for a week, a month, a year, and thousands more who participated vicariously or worked to extend the struggle for freedom and equality into Northern communities. These women were ready to hear what their Southern sisters had to say. The debate within Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) which started in response to Hayden and King’s ideas led, two years later, to the founding of the women’s liberation movement.

Thus, the fullest expression of conscious feminism within the civil rights movement ricocheted off the fury of black power and landed with explosive force in the Northern, white new left. One month after Hayden and King mailed out their memo, women who had read it staged an angry walkout of a national SDS conference in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. The only man to defend their action was a black man from SNCC.

Footnotes

1. See Gerda Lerner, The Grimke Sisters From South Carolina: Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition (New York: Schocken, 1971), 161-62.

2. Confidential interview; Judith Brown to Anne Braden, September 19, 1968, Carl and Anne Braden Papers, Box 82, State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

3. Elizabeth Sutherland, ed; Letters From Mississippi (New York: McGraw- Hill Book Company, 1965), 22-23.

4. Interview with Mimi Feingold; Dr. Sidney Silverman to Heather Tobis, July 21, 1964, Elizabeth Sutherland Papers, State Historical Society of Wisconsin; Heather (Tobis) to “my brother” in Sutherland, ed., Letters, 150; interview with Heather Tobis Booth, November 5, 1972.

5. Quoted in Cleveland Sellers, The River of No Return: The Autobiography of a Black Militant and the Life and Death of SNCC (New York: William Morrow, 1973), 39.

6. Howard Zinn, SNCC: The New Abolitionists (Boston: Beacon Press, 1965),

7. James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries: A Personal Account (New York: Macmillan, 1972), 235, 238-39. Avivia Futorian to unknown, July, 1964, Sutherland Papers, State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

8. Interview with Mary King; “Job Description: Mary King, Communications,” carbon copy, n.d., Mary King’s personal files.

9. Interview with Cathy Cade.

10. Interview with Mimi Feingold, July 16,1973, San Francisco, California.

11. Interview with Mary King. 12. Sutherland, ed., Letters, 111- 1 12, 229-230. 13. Len Holt, The Summer That Didn’t End (New York: William Morrow, 1965),

12; Interview with Vivian Rothstein, July 9, 1973, Chicago, Illinois.

13. Len Holt, The Summer That Didn’t End (New York: William Morrow, 1965), 12; Interview with Vivian Rothestein, July 9, 1973, Chicago, Illinois.

14. Interview with Dorothy Burlage.

15. “News from SCEF” by Anne Braden (typed), April 30, 1962, and “Statement by Diane Nash Bevel” issued April 20, 1962, (Handwritten draft), Carl and Anne Braden Papers, Box 47, State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

16. Interviews with Jean Wiley, July 26, 1973, Washington, D.C.; Gwen Patton, June 20, 1973, Washington, D.C.; Fay Bellamy, June 29,1973, Atlanta, Georgia.

17. Forman, Making, 276; Interview with Mimi Feingold.

18. Interviews with Fay Bellamy; Mary King; Ella Baker, July 31, 1973, New York City; Cathy Cade; Nan Grogan, June 28, 1973, Atlanta, Georgia; Jean Wiley; Betty Garman and Jean Wiley, July 26, 1973, Washington, D.C.

19. “To: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, From: Joni Rabinowitz, Southwest Georgia Project,” April 8-21. (1963) Joni Rabinowitz’s personal files.

20. This conclusion is inferred from interviews with Fay Bellamy, Gwen Patton, Jean Wiley, and Betty Garman.

21. Interviews with Cathy Cade, Vivian Rothstein, Sue Thrasher, and Nan Grogan.

22. Interview with Staughton Lynd, November 4, 1972, Chicago, Illinois.

23. Interview with Mary King.

24. Interview with Dorothy Burlage.

25. Confidential interviews.

26. Interview with Jimmy Garret, July 16, 1973, Washington, D.C.

27. Interview with Staughton Lynd; interview with Nan Grogan.

28. Interviews with Gwen Patton; Jean Wiley.

29. Confidential interview.

30. Interview with Howard Zinn, August 7,1973, Boston, Massachusetts; Josephine Carson, Silent Voices: The Southern Negro Woman Today (New York: Delacorte Press, 1969); Zinn, SNCC.

31. Interview with Dorothy Burlage; Mary King.

32. Casey Hayden and Mary King, “Sex and Caste: A Kind of Memo,” Liberation (April, 1966), 35-36.

Tags

Sara Evans

Sara Evans has been active in the civil-rights, anti-war, and the women’s movements in the South for many years. This article is adapted from a chapter in her manuscript, “Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil-Rights Movement and the New Left, ’’ to be published by A. A. Knopf. Sara is currently an assistant professor of history at the University of Minnesota. (1977)