Southern states lack adequate disclosure of fracking's chemical hazards

Most of the states where fracking is taking place that do not require any public disclosure of the chemicals used in in the controversial drilling process are in the South, and Southern states are also among those with weak disclosure laws.

That's the finding of a new report from OMB Watch, a nonprofit that promotes government transparency and accountability. Titled "The Right to Know, the Responsibility to Protect: State Actions Are Inadequate to Ensure Effective Disclosure of the Chemicals Used in Natural Gas Fracking," the report looks at disclosure policies in those states where the controversial natural gas drilling method is used.

It finds that "public information about these chemicals is spotty and incomplete at best, and important safeguards are missing," according to OMB Watch's announcement of the report's release.

There are seven states with significant gas drilling activity that do not require any public disclosure, and five of them are in the South: Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Virginia and West Virginia. The other two states in this group are Kansas and Utah.

Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas are among the 17 states with inadequate protections. North Carolina, where lawmakers recently legalized fracking in a contentious vote, is not included in the report as the state is just beginning the process of writing regulations.

OMB Watch measures the effectiveness of the states' disclosure policies according to their inclusion of four elements:

1. Is baseline data collected before the drilling begins?

2. Is chemical disclosure comprehensive, specific, and timely?

3. Are there limits on "confidential business information" exemptions?

4. Is information readily available to the public online?

"No state has yet established all of the elements of a chemical disclosure policy strong enough to ensure the quality of the water and the health of communities near gas wells," the report finds. While Colorado comes closest, it does not require baseline studies of air and water quality.

As OMB Watch explains, state regulations are critical because of the federal government's failure to regulate fracking. The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 aims to prevent toxic substances from being injected near underground drinking water supplies, but in the 1990s the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency claimed it lacked the authority to regulate fracking under that law.

In response to a citizen lawsuit brought against EPA by an Alabama family whose well was contaminated by nearby fracking operations, an appeals court in 1997 ordered the the agency to reconsider its position. However, the EPA failed to take action, and in 2005 Congress inserted a clause into a federal energy bill that officially exempted fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act. Championed by Vice President Dick Cheney, that exemption is commonly known as the "Halliburton loophole," named for the Texas-based company Cheney once led that's heavily involved in fracking.

But states have been slow to step into the regulatory gap, as the report notes:

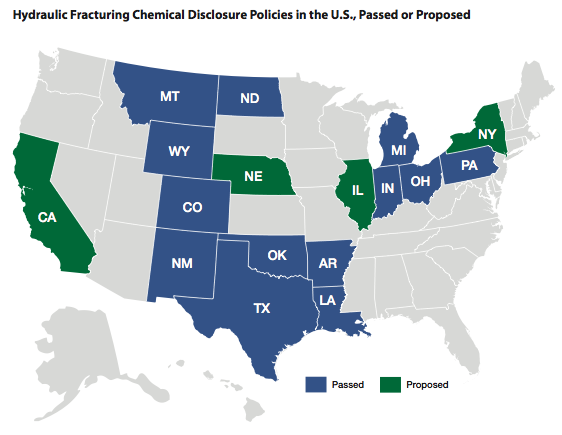

Currently, at least 30 states are engaged in natural gas drilling; six states have more than 30,000 wells; another five have between 10,000 and 30,000 wells. Yet only 13 states with active gas reserves have passed laws or established rules requiring even basic public disclosure about the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing, and only four of those 13 require that any information be provided before drilling occurs so that authorities can monitor potential changes in water and air quality over time. Four other states have proposed hydraulic fracturing policies. Most of the state laws or rules that do exist contain loopholes that allow companies to refuse to disclose the ingredients in the fracking products they use by claiming that these ingredients are "confidential business information" -- implying that making the information public would give a competitor an unfair advantage.

To read the full report, click here.

(Map from the OMB Watch report.)

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.