Who is most at risk from Hurricane Isaac?

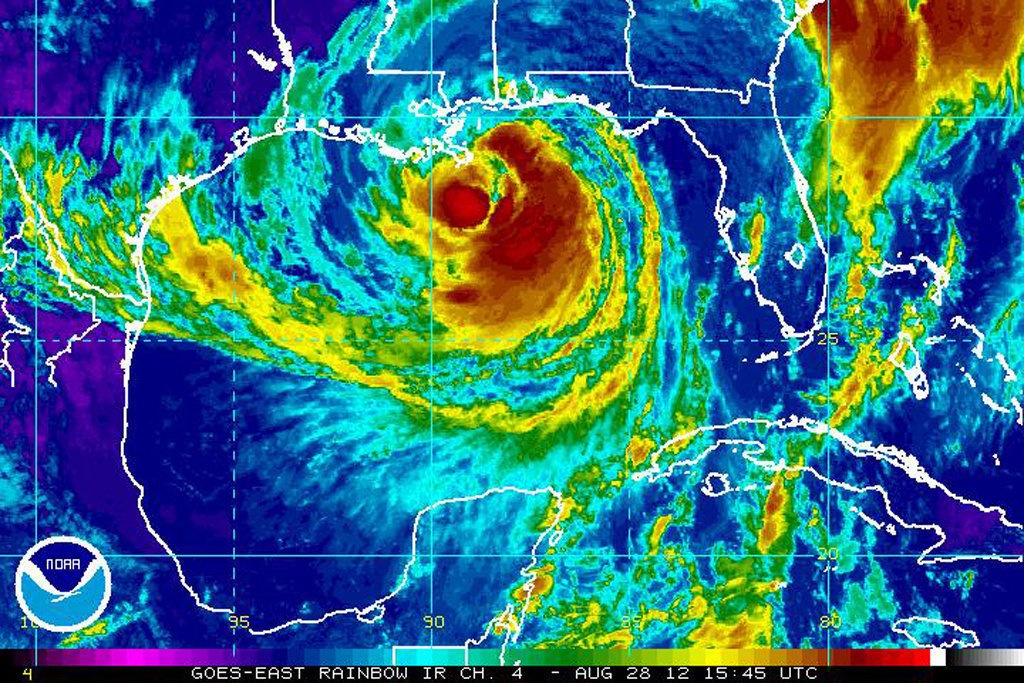

At 11:20 a.m. on Tuesday, August 28, Tropical Storm Isaac became Hurricane Isaac, with the National Hurricane Center reporting the storm's winds had grown to 75 miles per hour.

The growing storm is now projected to hit South Louisiana on Tuesday evening, almost exactly seven years after Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast. In 2005, the resulting storm surge led to 53 levee breaches in New Orleans, flooding the city, and a federal disaster declaration that covered 90,000 square miles across the Gulf.

Is New Orleans likely to face the same problems in 2012 that it did in 2005?

Nobody is expecting Isaac to be as devastating as Katrina, at least in New Orleans. For one, Katrina was a much stronger storm. Two, most of the $14 billion in work to improve New Orleans' storm defenses has been largely completed, improving the levees and flood walls, as well as improving the city's water-pumping system.

But that's just New Orleans. In 2008 with Hurricane Gustav, New Orleans was said to have avoided a "direct hit" of Katrina's caliber -- but 30,000 residents were evacuated and many along the Louisiana coast were displaced -- some permanently.

Thousands of miles of coastal communities from Alabama to Texas were affected, both short-term from massive flooding, and long-term, from dangers such as the toxic sludge churned up in the bayous and deposited in coastal neighborhoods.

Oil spills are a constant danger as well: In 2005, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita caused 124 offshore spills that dumped more than 743,000 gallons of pollution into the ocean, despite the later insistence by politicians that the storms caused no problems with oil rigs.

When it comes to storm defense systems, even neighborhoods close to New Orleans are still at risk, as Mark Schleifstein of the New Orleans Times-Picayune noted in an interview with NPR:

[Risk of flooding] still is a problem for communities that live outside of the levy system. There are several such communities on what's called the West Bank, the south side of the Mississippi River in the New Orleans area that are out of the new levee system there. Several thousand people who live in homes that are not protected.

Within New Orleans, the city continues to be tested in its ability to keep water out -- and remove the water that gets in. In the summer of 2012, a series of heavy rains overwhelmed the city's 1,500 miles of patchwork drainage pipes. The problem was compounded by the city's storm defense levees, which created a "bathtub" effect, flooding city streets in knee-deep drainage water.

As the New Orleans Citizen Sewer, Water & Drainage Management Task Force noted in an April 2012 report [pdf], the city's "pipe-pump-canal drainage system can barely accommodate a 1-year rainfall event" -- two inches per hour at peak; just over four inches over 24 hours. That means the city will likely face a "severe flood event" at least once a year; the system will quickly fail with hurricane-level rains.

But that assumes the system is working. In 2005, 40 city water pumps catastrophically failed after Katrina struck -- with accusations of a rigged bidding process in the background -- further exacerbating flooding in New Orleans. Today the biggest problem is bad drainage -- "mass pipe breakages," according to the task force report, and excessive runoff into non-porous roads and sidewalks.

As usual, the problem is compounded by an inexplicable bureaucracy: As the task force notes with clear bewilderment, 1,288 miles of New Orleans drainage pipe are run by one arm of government (City/Department of Public Works) with a budget of just over $3 million; the other 235 miles are run by another arm (the Sewage and Water Board of New Orleans) for more than $40 million -- and neither are solving the problem.

In short, the rains from Hurricane Isaac alone will likely cause severe flooding across New Orleans. And for the rest of the Gulf Coast, lacking both the city's storm defenses and the media attention given to the Big Easy, communities may be even more vulnerable.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.