With public financing's demise, special-interest money pours into NC court races

Supreme Court candidates Eric Levinson and Robin Hudson during a recent TV interview. Levinson is hoping to unseat Hudson as associate justice, and the two have combined for over $700,000 in ad spending in this year's most expensive state court race. (Image is a still from the UNC-TV interview.)

When the North Carolina legislature struck down the state's popular judicial public financing program last year, it also raised the amount one can donate to judicial campaigns from $1,000 to $5,000. The move opened the floodgates for far more special-interest money to flow into state Supreme Court campaigns, whose main source of funding even while the public campaign fund was in effect was lobbyists and lawyers.

A recent Follow NC Money/Facing South analysis of public records finds that N.C. Supreme Court candidates have, on average, raised three times the amount of individual contributions so far this cycle than candidates in 2010 and 2012. Meanwhile, outside groups unaffiliated with the campaigns and financed by special interests have also spent generously on judicial races.

Altogether, candidates and outside groups have combined to spend over $3.1 million on ads for state Supreme Court and Court of Appeals races so far this year.

To understand how much the financial landscape of judicial races has changed in North Carolina, consider the example of state Supreme Court Associate Justice Robin Hudson, a registered Democrat.

When she was first elected to an eight-year term in 2006, Hudson participated in the public financing program for judicial races. She raised just over $81,000 in small individual contributions, easily qualifying her for $211,000 of public money to promote her campaign. Her total expenses that election were about $274,000.

Eight years later, running for re-election with the judicial public financing program dismantled, she finds herself in a much different position. At the end of this year's second quarter, she had already raised $415,000 in individual contributions -- five times her 2006 total. In the primary, she spent $210,000 on television, radio, print and online advertising, defending herself against a controversial attack ad.

Hudson's total expenditures so far this election cycle are over $530,000 -- twice her 2006 total. Meanwhile, her opponent, Eric Levinson, a registered Republican, had raised $315,000 in individual contributions by June 30 and has spent almost $348,000 on ads to date.

Candidates spend big on ads

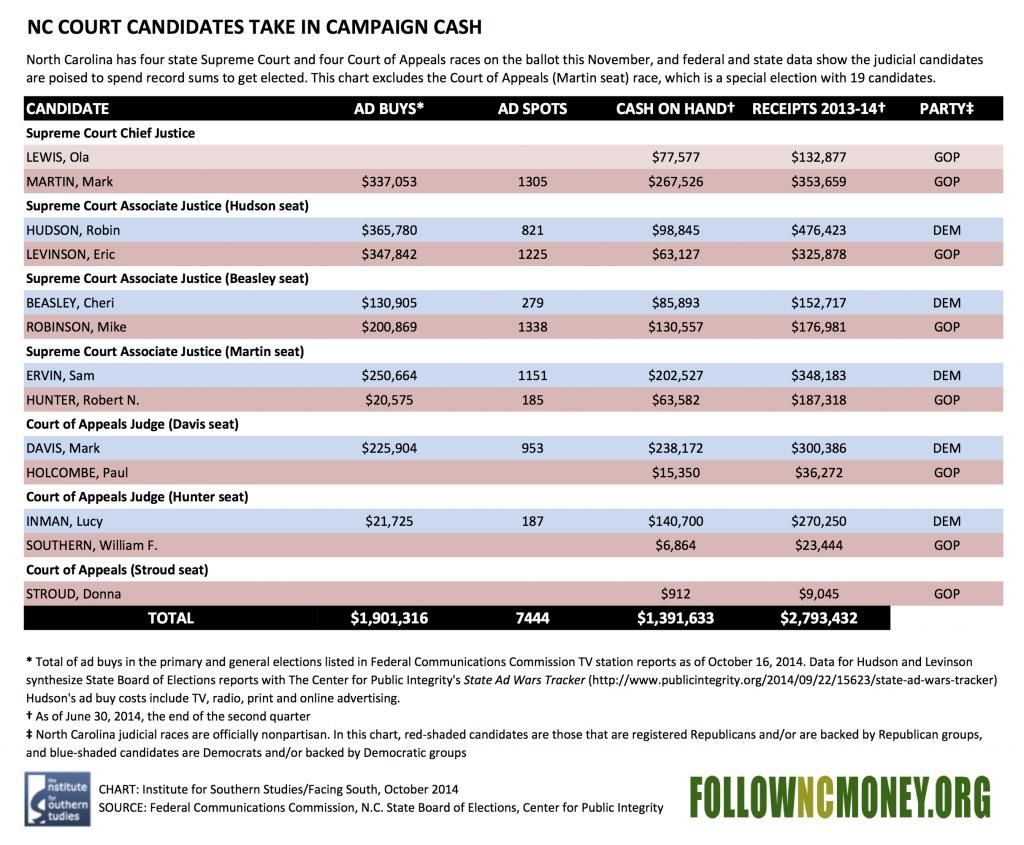

The Supreme Court has four open seats in 2014, as does the Court of Appeals. Of these eight races, Follow NC Money/Facing South has tracked spending data on six: the four Supreme Court races, and the Mark Davis-Paul Holcombe and Lucy Inman-Bill Southern Court of Appeals races. In another Court of Appeals race, Donna Stroud is running unopposed, while another involves a special election among 19 candidates begun in August to fill the seat of retiring judge Robert C. Hunter. These data are not included.

The upshot? North Carolina residents should brace for an onslaught of TV ads for judges. In the run up to the November election, the candidates together have booked a total of 6,703 ads at 15 TV stations, with many beginning to air on Oct. 14, at a total cost of over $1.5 million.

Hudson is spending the most on total ads this year with $365,780. Mark Martin, a Republican running for chief justice against fellow Associate Justice Ola Lewis, also a Republican, leads the pack in general election ad spending, forking over $337,053 for 1,305 spots. Martin was part of the 20 percent minority of judges who did not participate in the public financing program in the past.

This year's Martin-Lewis race for chief justice is an example of how lopsided spending can be in a privately funded judicial race; under public financing, races were monetarily competitive as long as candidates raised 350 small contributions from registered North Carolina voters to qualify for the public funds. But at the end of the second quarter, Martin had raised more than $353,000 and had over $267,000 on hand, while Lewis had raised only $133,000 and had approximately $78,000 on hand. As a result, Martin has spent hundreds of thousands on ads, while Lewis has spent nothing.

Whether the campaigns spend more on average post-public financing remains to be seen, but the biggest spenders appear to be spending more now than in past years. In the Supreme Court races, Martin, Levinson, Hudson, and Sam Ervin -- a registered Democrat running for associate justice after losing to Paul Newby in 2012 -- all have higher total campaign expenditures than the biggest spender in 2012 (Newby) and in 2010 (Hunter).

In the Court of Appeals races, Mark Davis’ $288,000 in expenses thus far exceeds the expenditures of the biggest spenders in 2010 and 2012 by $44,000 and $25,000, respectively.

Here is a table detailing the candidates' campaign finance information as of Oct. 16 (click on it for a larger version):

Outside money still in play

Outside money, a growing factor in elections since the U.S. Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United decision loosening corporate spending rules, continues to jam the airwaves with ads.

In 2012, outside groups poured over $2.8 million into the Supreme Court race between Newby and Ervin, which saw nearly $3.5 million in total spending. But even then, the candidates themselves used the public financing program, and 72 percent of combined campaign spending by Newby and Ervin came from public funds.

So far this year, outside groups have spent less than in 2012 -- close to $1.3 million. Leading the spending with $899,000 is Justice for All NC, a state-based 527 group that has served as a funnel for political money. But much of the 2014 primary's outside spending happened during the final few weeks before the election, so the same could happen again this time.

Here is a table that breaks down all spending in state court races this year as of Oct. 16 (click on it for a larger version).

Ad purchases by outside groups can have a "crowding out effect," Supreme Court candidate Hunter told Facing South. Outside groups often make massive ad buys, leaving little primetime ad space for the candidates' campaigns and driving up prices.

But this time around, the opposite may have occurred: With over 6,700 ad spots bought by state court candidates from Oct. 14 until election day, there may not be many openings left, and they are sure to be expensive.

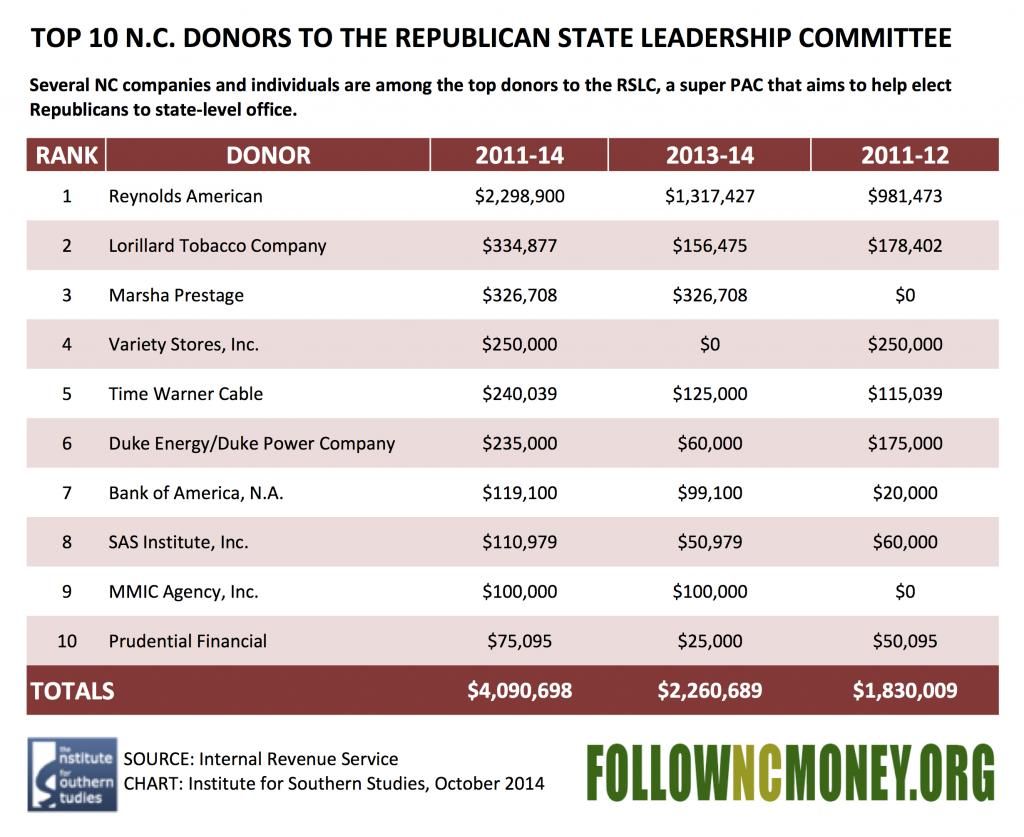

Nonetheless, the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC), which funded Justice for All's ad campaign in the primary, has pledged to spend millions on state court races this year through its "Judicial Fairness Initiative."

The RSLC is a major recipient of North Carolina corporate dollars, with Reynolds American and Lorillard, two big tobacco companies that recently merged, leading the pack, giving a combined $2.6 million over the last four years. The state's fourth-largest donor to the RSLC since 2011 is Variety Stores, Inc., the company headed by GOP mega-donor and former state budget director Art Pope, who had a hand in killing judicial public financing. Coming in at number six is Duke Energy, which has had numerous cases before the courts recently.

Progressive Kick, an independent expenditure group that supports judicial public financing, has pledged to spend in judicial races. However, the group had raised only "tens of thousands of dollars" as of earlier this month.

Ethical questions in high stakes cases

Companies and organizations that are significant political donors often have matters before the courts, and state ethics laws may not address potential conflicts of interest sufficiently.

For example, Duke Energy has had $38.8 billion dollars at stake in high court cases in North Carolina since 2011, according to the Center for American Progress. These include cases about rate hikes, a merger with Progress Energy, and cleanup of groundwater contamination from its coal ash pits. The state Supreme Court has recently taken up Duke's appeal of this latter lower court ruling, bypassing the Court of Appeals.

Other contentious cases before the courts that involve big political spenders include a case regarding the state's 2011 redistricting maps, the control of which was a focus of the RSLC in 2010, and a case that will determine the fate of private school vouchers.

Despite the obvious potential for conflicts of interest, the state's judicial code of conduct offers high court members vague ethical standards, merely requiring them to "avoid impropriety." But few Supreme Court justices have recused themselves from cases recently. This year, only Justice Cheri Beasley has done so, and in 2013, only Beasley, Hudson, and Barbara Jackson recused themselves from cases.

In its analysis of recusal rates in light of increased campaign cash, the Center for American Progress ranked North Carolina last in the nation, tied with Wisconsin. But as court candidates raise more money and campaign like politicians, their connections to the parties before them are likely to come under increased public scrutiny.

Tags

Alex Kotch

Alex is an investigative journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, and a reporter for the money-in-politics website Sludge. He was on staff at the Institute for Southern Studies from 2014 to 2016. Additional stories of Alex's have appeared in the International Business Times, The Nation and Vice.com.