Americans disenfranchised for crimes would be able to sway Senate races

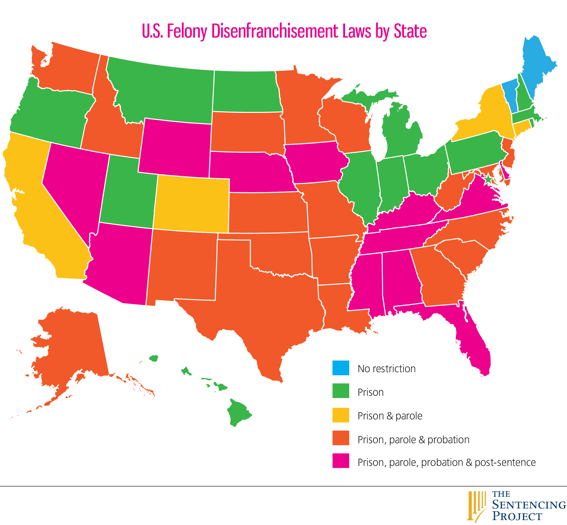

Almost 6 million Americans are unable to vote because of laws that prohibit voting by people with felony convictions. And because of racial disparities in the criminal justice, such laws have resulted in one of every 13 African Americans being unable to vote. (For a larger version of this map, click here.)

Almost six million Americans cannot vote because of laws that disenfranchise people for felony convictions -- but if their voting rights were restored, they would likely be able to sway six close U.S. Senate races and four close gubernatorial races.

State-by-state data from the Sentencing Project and polling averages from RealClearPolitics.com suggests that seven states -- Alaska, Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, and North Carolina -- have Senate races that are so close that if all adults convicted of felonies in those states could vote and voted for the same candidate they would likely change the outcome of the elections.

In four states -- Colorado, Georgia, Florida, and Kansas -- repeal of felony disenfranchisement laws would restore voting rights to enough people to sway tight gubernatorial elections.

"This is fundamentally a question of democracy," said Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit working to reform the U.S. criminal justice system.

Since the 1960s, the number of Americans convicted of crimes has increased over 600 percent. As a consequence of mass incarceration and harsh state laws that continue to disenfranchise people with felony convictions even after they've completed their sentences, the Sentencing Projects estimates that 2.6 million Americans have permanently lost their voting rights.

U.S. felony disenfranchisement policies are the most extreme among industrial nations worldwide. But critics of these policies have gained new traction in recent years, a trend led by U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, who in February called for the repeal of such laws, which disproportionately affect African Americans.

The Sentencing Project estimates that one in 13 African Americans has lost the right to vote due to state felon disenfranchisement laws. In three states -- Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia -- such laws have disenfranchised more than one in five black adults.

In Florida, over 10 percent of the state's population has been disenfranchised due to felony convictions. Former governor Charlie Crist, who's running again this year as a Democrat, issued an executive order restoring voting rights to all ex-felons in 2007. But after defeating Crist, current governor and Republican candidate Rick Scott rescinded the executive order in 2011.

In Kentucky, where Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell appears to be up about five points in polls, over seven percent of the state's population cannot vote because of felony convictions.

The following graphic shows the states where elections for U.S. Senate and governor could be affected if all adults convicted of felonies could vote:

Broad effects on electoral politics

The disenfranchisement of people convicted of felonies has broad effects on U.S. politics. For example, incarceration affects Census results, since prisoners are counted as residents of the towns where the prisons are located. This shifts state and federal representation from prisoners' home communities to the often rural and overwhelmingly white districts areas where prisons are located.

At the same time, felon disenfranchisement discourages voters and those around them from engaging in politics, which in turn affects policies around crime and incarceration.

Laws disenfranchising those convicted of crimes began with a British tradition colonists took to North America. After Reconstruction, many of these laws were expanded to restrict the number of African Americans who could vote.

Mauer pointed out this while this country was founded as an experiment in democracy, it was a very limited experiment, with white male property owners granting themselves the right to vote while excluding women and African Americans.

"We look back on those exclusions with a great deal of embarrassment," Mauer said. "And today people with felony convictions are the largest group of people excluded from the right to vote."

Further, many criminal justice advocates -- including groups representing correctional and probation and parole professionals -- have argued that felony disenfranchisement makes it harder for people to reintegrate into their communities after prison sentences.