Mapping those affected by North Carolina's factory-farm protection bill

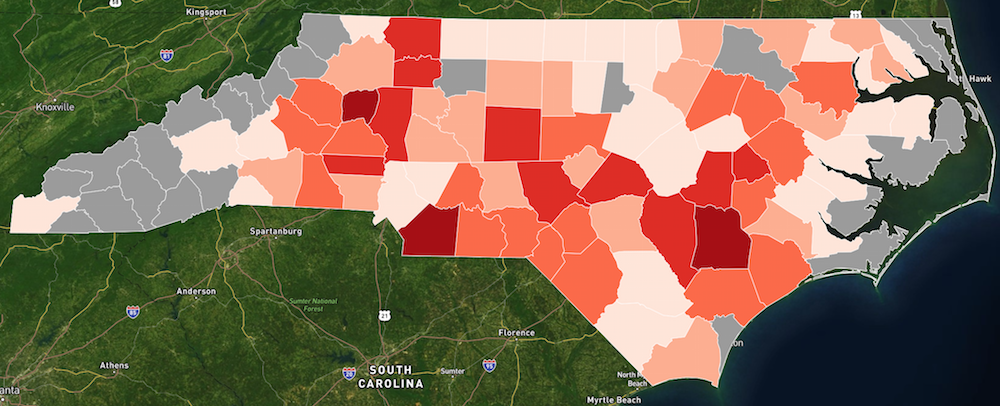

This Environmental Working Group map shows the North Carolina counties with the greatest number of residences located within a half-mile of a factory hog or chicken farm and/or open-air pits that hold hog waste; the darker the red, the greater the number. For an interactive version of the map, click here.

As legislation to limit North Carolina residents' ability to collect damages in civil lawsuits against factory farms makes its way through the General Assembly, a new mapping initiative offers a clearer picture of how many people could be affected by the controversial proposal and where they live.

This week the Environmental Working Group released an investigation and interactive map that shows every residence in the state located near an industrial-scale hog or chicken farm or open-air pits that hold swine waste. It found more than 60,000 residential parcels that are home to an estimated 160,000 people within a half-mile of such facilities.

Given studies showing that the pollution, odor and health effects from factory farms can carry as far as three miles, as many as 360,000 residences and an estimated 960,000 people in all could be affected by the North Carolina legislation.

But all North Carolinians would not be affected equally: The state's factory farm and animal waste pits are concentrated in two geographic bands, one running through eastern North Carolina's coastal plain and another through the Blue Ridge foothills in the western part of the state.

In eastern North Carolina — part of the South's Black Belt region and home to a growing Latino community and the Lumbee Tribe — the concentration of factory farms is greatest. Indeed, one University of North Carolina study found that the proportions of African Americans, Hispanics and American Indians living within three miles of an industrial hog farm in the state are 1.54, 1.39 and 2.18 times higher, respectively, than the proportion of non-Hispanic whites.

In Duplin County, for example, just north of the port city and tourist destination of Wilmington, approximately 4,660 residences housing an estimated 12,489 people – more than a fifth of the county's population – are located within a half-mile of a factory farm or manure pit. Meanwhile, Duplin County's population is 29 percent African-American and 15 percent Latino, far greater than the state average of 21.5 percent and 8.4 percent, respectively.

"If this bill becomes law, you have to wonder which polluting industry will get legal immunity from North Carolina's legislators next," said EWG President Ken Cook. "And how many more thousands of North Carolinians will be deprived of their access to justice if the legislature turns the state over to polluters?"

Bailing out the industry

The controversy began last month when a group of Republican state lawmakers — many of them generously backed by the livestock industry — introduced House Bill 467 and a companion measure, Senate Bill 460, to limit compensatory damages in so-called private "nuisance" lawsuits, which address unlawful and unreasonable interference with the enjoyment of one's property.

In the case of permanent nuisances, the legislation would limit damages to "the reduction in the fair market value of the plaintiff's property caused by the nuisance, but not to exceed the fair market value of the property." In the case of temporary nuisances, it would limit damages to "the diminution of the fair rental value of the plaintiff's property caused by the nuisance."

The proposals came with just such a lawsuit underway against Murphy-Brown LLC, the hog-producing subsidiary of Virginia-based Smithfield Foods, which in turn is owned by China-based WH Group, formerly known as Shuanghui Group, the world's leading pork company. More than 500 eastern North Carolina residents sued Murphy-Brown in 2013, complaining of sickening stenches, swarming flies, chronic illnesses and piles of animal carcasses left in roadside "dead boxes." The trial could begin as soon as this summer.

The legislation triggered warnings from a former state Supreme Court justice and a former state legislative leader, both Republicans, that it was probably unconstitutional since it aims to benefit a particular industry. It was also met with protests from environmental groups and even some Republican legislators like Rep. John Blust, a Greensboro area attorney who introduced an amendment to block it from applying to current litigation.

"We don't need to be, at the last minute, rushing in to bail out a defendant — and that's what's happening," Blust said during debate over the bill.

The bill including Blust's amendment passed the House by a vote of 68 to 47. But the version of the legislation now pending in the Senate agricultural committee would still apply to ongoing litigation.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.