The culmination of the N.C. legislature's war on the courts

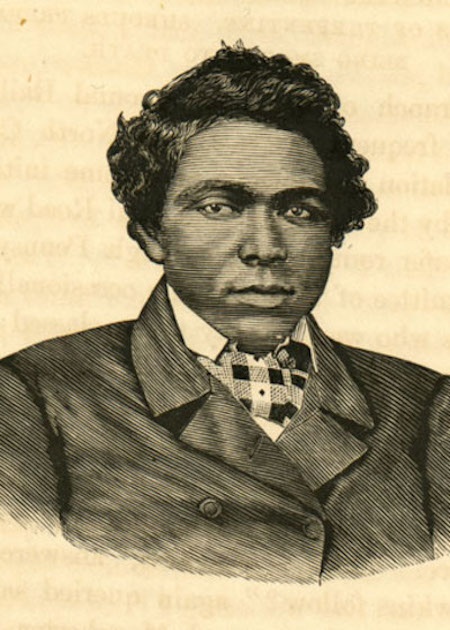

Abraham Galloway, a former fugitive slave who returned to North Carolina and helped draft the state's 1868 constitution, called the judiciary chosen by the Confederate state legislature a "bastard born of sin and secession" and helped move the state to judicial elections. Now some of the state's Republican lawmakers want to revert to that pre-Reconstruction system. (Engraved portrait of Galloway from the State Library of North Carolina's NCpedia website.)

Looking back, 2013 was an important year for the North Carolina General Assembly. A new GOP supermajority took office after Republican legislators gerrymandered their own election districts in 2011. In July 2013, just weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act, the state's lawmakers passed a bill that created a voter ID requirement, cut early voting, and made it harder to vote in other ways.

The bill was also the beginning of the legislature's ongoing attacks on the state's judicial branch. It allowed more campaign cash into North Carolina's judicial elections by eliminating the popular, nationally-renowned public financing program for judicial candidates. The program kept judges from having to raise large campaign donations, and it helped foster diversity on the courts. As Facing South reported, a compromise to continue funding the program was thwarted by Art Pope, a millionaire GOP campaign donor and former Gov. Pat McCrory's budget director.

Federal courts have since struck down the parts of the bill that dealt with voting. The trial court found that legislators, after seeking out data on the types of identifications that African-American voters lacked, had targeted those voters "with almost surgical precision." The U.S. Supreme Court upheld this finding and confirmed that North Carolina legislators discriminated against black voters when they gerrymandered election districts. Legal challenges to more recent voting laws are pending in state courts.

The court rulings to protect voting rights have incensed state legislators, who harshly criticized the federal courts and dragged their feet in redrawing gerrymandered election districts. Legislators have also responded by ramping up what Democratic state Rep. Joe John, a former judge, called a "war" on the judiciary — a war that former North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Bob Orr, a Republican, has argued is motivated by the litigation over racial gerrymandering.

As part of this assault on a co-equal branch of government, the General Assembly has made judicial elections partisan, slashed the size of the Court of Appeals to prevent appointments by the governor, and floated a court packing plan that would have essentially overturned the will of the voters in November 2016. Legislators have also introduced bills to chip away at the governor's authority to fill vacant judgeships and to give political parties a role in choosing judges.

Now the General Assembly is considering a plan to gerrymander judges, as well as two constitutional amendments to change how judges are chosen. One amendment would slash judges' terms in office to only two years — the shortest in the nation. This would require North Carolina judges to constantly campaign and raise funds from donors.

Taking power from the people

Another proposed amendment would be the N.C. General Assembly's ultimate power grab: It would essentially transfer the power to choose judges from voters to the legislature. Legislators have called their proposal a "merit selection" plan, but that label is highly misleading.

The merit selection commission would review applications for judgeships and decide whether candidates are qualified or not. Then legislators would choose three candidates from the wide pool of qualified candidates, and the governor would choose from among the General Assembly's three handpicked candidates.

In states with true merit selection systems, the commissions are charged with deciding who is most qualified, not just sifting out the unqualified candidates. In these states, the commissions narrow down the choices, not legislators.

Republican state Sen. Paul Newton presented the controversial plan at a recent hearing of the legislature's Select Committee on Judicial Reform and Redistricting, which could soon vote on the proposal. Even some of Newton's Republican colleagues questioned whether voters would approve the amendment. A conservative pollster recently found that 66 percent of North Carolinians surveyed opposed giving up their right to elect judges. In the last few decades, no state has approved a constitutional amendment giving up voters' right to do so.

Only two states, Virginia and South Carolina, give legislators the power to choose judges, and the Brennan Center for Justice testified before the North Carolina legislature about the conflicts of interest that can result from such a system.

Newton claimed North Carolina legislators would choose the three most qualified candidates to send to the governor. But a merit selection commission would be much more effective at assessing judges' qualifications than a group of politicians. The General Assembly's record of tinkering with the courts for partisan advantage suggests that they would appoint judges they think will fall in line with their agenda.

Deconstructing Reconstruction

The legislative selection amendment would bring back the kind of system that North Carolina eliminated 150 years ago. Until the Civil War, North Carolina's legislature chose its judges. But the state's Reconstruction legislature, like some others in the South, changed how judges were chosen to get Confederates off the bench.

The convention that drafted the 1868 North Carolina Constitution included African-American delegates and others who moved to the state after the Civil War. A history of the convention, written in 1911 by Judge Henry Connor, disparaged the "Northern men … whose views and sympathies were hostile to the white people." Connor said that "the vote against ratification was entirely by the whites," and he criticized the constitution for allowing black citizens to vote. The relatively progressive document also banned slavery and abolished property requirements for voting.

The 1868 Constitution generally gave the legislature less power, shifting more to the governor and voters. The delegates to the convention rejected a proposal to preserve the state's system of letting the legislature choose judges. Abraham Galloway, a black delegate who had returned to North Carolina after fleeing to Pennsylvania to escape slavery, called the then-existing judiciary "a bastard born of sin and secession." The constitutional convention wanted new judges chosen in elections that were now open to African-American and poor white men — not judges picked by the Confederate legislature.

While the North Carolina Constitution was radically changed after the end of Reconstruction and during the Jim Crow era to restore some legislative power over the courts, judicial elections remained.

Professor Jed Shugerman's history of judicial elections, "The People's Courts," discussed how a few Southern states moved from judicial elections to merit selection in response to black voters regaining some power from 1950 to the early 1970s. Birmingham, Alabama, became the second jurisdiction in the U.S. to adopt merit selection in 1950, following the state of Missouri. Shugerman explains how racist Democratic politicians had implemented new restrictions on voting, and Birmingham's "white establishment worried that judicial scrutiny might jeopardize all of their voting restrictions against both black voters and poor whites."

Shugerman also notes that in the early 1970s, when Tennessee and Florida became the only Southern states to use merit selection to choose their supreme courts, both states had seen "the most progress in registering black voters." White southerners' interest in judicial appointments over elections, he concluded, was revived by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and Supreme Court rulings to protect civil rights.

Some North Carolina legislators have also discussed amending the state constitution to add a voter ID requirement, which research has shown disproportionately lowers non-white voter turnout. Though a voter ID amendment would not override federal voting rights protections, it could tie the hands of state courts in addressing any discriminatory voter ID laws.

Amending the North Carolina Constitution first requires state lawmakers to approve the proposed amendment by a 60 percent margin and then approval from a majority of the voters. At a recent hearing, Republican state Rep. John Blust acknowledged that passing a legislative selection referendum would be an uphill battle. No state has approved a constitutional amendment giving up the right to elect judges since the 1980s.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.