How gerrymandering blunted the South's blue wave

Participants in the 2016 Moral March on Raleigh protested Republicans' gerrymandered electoral maps, which hurt Democrats in this year's congressional midterms. (Photo by Stephen Melkisethian via Flickr.)

In the 2018 elections in North Carolina, 48 percent of voters chose a Democrat to represent them in the U.S. House. But after the elections were over, only three of the state's 13-member House delegation — 23 percent — will be Democrats.

In Arkansas and West Virginia, two out of five voters opted for a Democratic U.S. representative in the 2018 elections. But both states will send all-Republican delegations to the U.S. House in January.

A Democratic surge in 2018 was expected to shake up politics, both in the South and nationally. Yet while Democratic voters turned out in record numbers, the force of the "blue wave" was blunted by two barriers: historic turnout by GOP voters, and Republican-engineered gerrymandering, especially in Southern states.

Nationally, the number of Democrats in the U.S. House roughly matches the number of votes cast for Democratic candidates. According to an analysis by Dave Wasserman and Ally Flinn of Cook Political Report, Democratic U.S. House candidates in 2018 received 52.8 percent of votes across the 50 states, close to the 53.3 percent share they are projected to make up of incoming U.S. House members (with four races still too close to call).

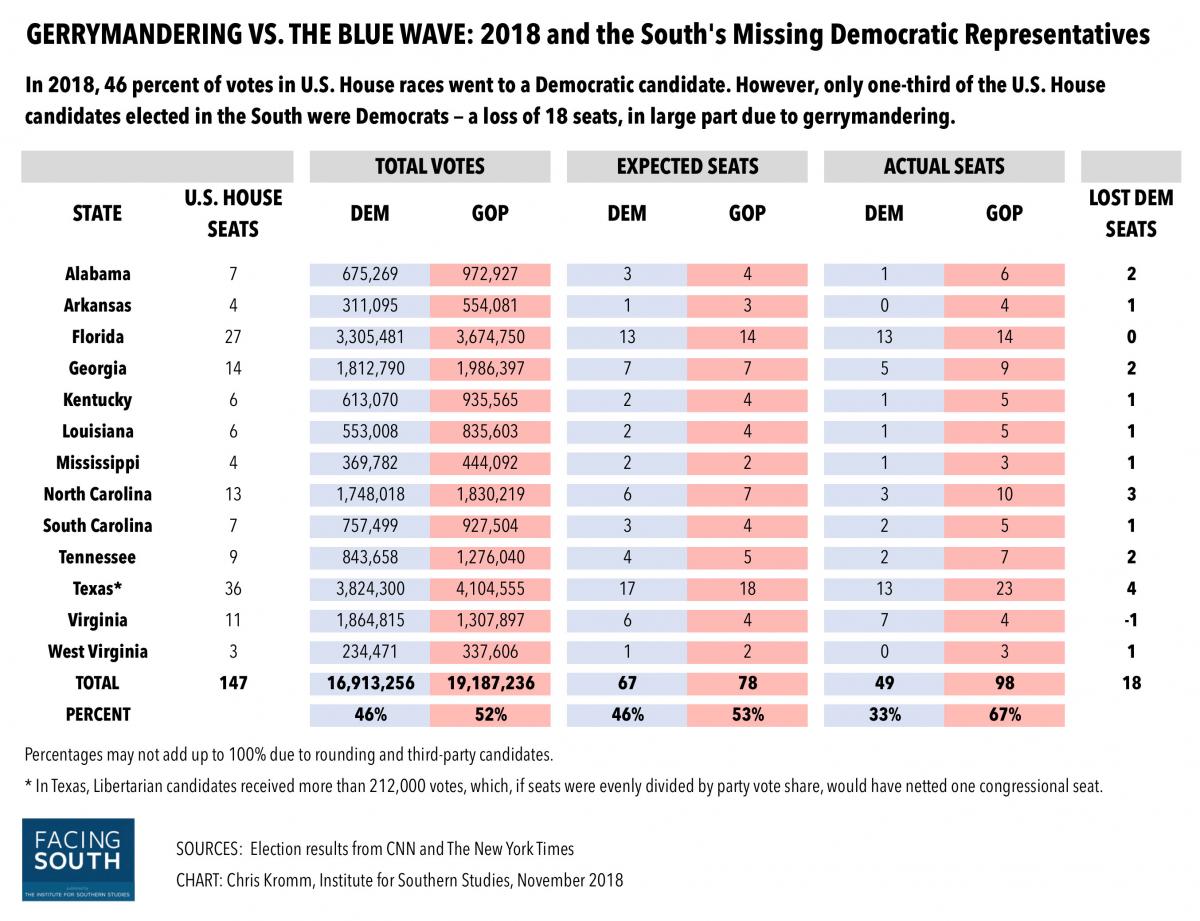

But in the South, the picture is much different. A Facing South/Institute for Southern Studies analysis finds that, despite winning 46 percent of all votes cast for U.S. House candidates in the 13 Southern states, Democratic candidates prevailed in only a third of the races in 2018. To put it another way, if the South's share of U.S. House members matched the overall vote totals in 2018, Democrats would hold 67 of the region's 147 representatives. As it stands, they will send 49 to Washington — a "loss" of 18 U.S. House seats for Democrats in the South. (Click on the chart for a larger version.)

Losing Southern battlegrounds

Heading into the 2018 elections, there were about 28 U.S. House races that were projected to be especially close in the South. All but one were Republican-held seats that Democrats hoped to flip in pursuit of winning a majority in the U.S. House — which the party succeeded in doing, although with limited help from Southern states.

If current vote margins stand, Democrats will have ended up flipping just seven of the more than two-dozen battleground U.S. House races in the South. (In Georgia's 7th District, Republican Rep. Rob Woodall holds a 400-vote lead, but the race is still too close to call.) Democrats toppled Republicans in only a quarter of the South's hotly-contested seats.

Why was the blue wave so limited in the South? For one, while Democratic turnout soared above levels seen in 2014, Republicans also built on already-high turnout in the last midterms. As Michael McDonald of the Elections Project at the University of Florida noted, "Yes, there was a blue wave, but the red wave from 2010 and 2014 really didn't dissipate either. And so that's how we get these really close outcomes in some of the states."

But an even bigger culprit was gerrymandering. After the 2010 elections, Republican-led legislatures in the South redrew congressional districts to maintain political dominance. The GOP-drawn districts have been so overwhelmingly unfavorable to Democrats that most U.S. House seats in the South have been put out of play. As the political analysis website FiveThirtyEight argued before the elections:

The effects of Republican-controlled redistricting and racial polarization are so strong in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Tennessee that Democrats don't have any realistic pickup opportunities under any of the scenarios discussed here.

The prediction ended up being wrong about South Carolina: Democrat Joe Cunningham's narrow victory over Trump enthusiast Katie Arrington in South Carolina's 1st Congressional District was a highlight for Democrats in 2018.

But South Carolina was the exception to the rule. All of the other Democratic gains came in four Southern states: Florida, Georgia, Texas, and Virginia. All four have seen major demographic shifts in the electorate that, in select cases, allowed Democrats to overcome their GOP-friendly districts. Virginia has been trending blue in recent elections; in Florida, Georgia, and Texas, high-profile state races for U.S. Senate and/or governor helped mobilize the progressive base of young, African-American, Latinx, Asian-American and women voters.

The end result is clear: In the Facing South/Institute analysis, Florida was the only Southern state where the makeup of the congressional delegation ended up matching the vote totals for Democratic and Republican U.S. House candidates. In Virginia, Democrats actually narrowly over-performed their vote totals by one seat. Despite flipping the key 7th District, Georgia Democrats will have two fewer members of their state's U.S. House contingent than if the winners matched the number of party votes. In Texas, Democrats flipped the 32nd District but will end up four seats under their projected share.

The gerrymandering effect

For several election cycles, North Carolina has been a case study in the impacts of gerrymandering. After taking control of the state's General Assembly in 2010 and the governor's mansion in 2012, Republicans created what have been consistently rated as among the most heavily gerrymandered districts, locking in GOP control.

In a string of court decisions, North Carolina's maps have been repeatedly declared unconstitutional racial and partisan gerrymanders. Indeed, less than three months before the 2018 elections, a three-judge panel had again declared the state's congressional maps excessively partisan but held off on calling for new maps before Election Day.

Nationally, liberal pundits vexxed that partisan bias in the battleground states' congressional maps could prevent Democrats from taking a majority in the U.S. House. While that didn't happen, North Carolina and its GOP-tilted maps didn't do Democrats any favors. According to the Facing South/Institute analysis, a more equitable distribution of U.S. House votes would have added three Democrats to the state's congressional delegation, turning a 10-3 GOP advantage to 7-6.

The impact of gerrymandering in the South is especially clear when the results are compared to states where redistricting reform has lessened partisan influence in drawing congressional lines. An analysis from the Brennan Center found that, in 72 percent of the races where Democrats prevailed, congressional districts had been drawn by independent redistricting commissions or by courts, as opposed to the partisan process used in most Southern states. As the Brennan Center argues:

Numerous factors explain how Democrats decisively took back a majority in the House of Representatives last Tuesday. But one deserves particular attention: Nearly three in four of the seats Democrats flipped were in districts drawn by redistricting commissions or courts. Districts drawn through these fairer processes were far more competitive than those drawn by legislatures in states where one party had sole control and could use it to gerrymander.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.