The diverging fates of two N.C. lawyers who battled over voter suppression

When the North Carolina legislature passed a restrictive voting law in 2013, civil rights attorney Anita Earls warned that it would lead to "citizens turned away and not allowed to vote, more provisional ballots cast but many fewer counting, vigilante observers at the polling place and all disproportionately impacting black voters." Earls, who was then executive director of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice in Durham, filed a lawsuit challenging the law on behalf of voters.

The 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the law, which it said targeted black voters "with almost surgical precision." In crafting it, the Republican-led legislature had sought out data on how African Americans voted and included provisions in the law — among them a voter ID requirement — that would disproportionately impact them. The measure was announced just hours after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a provision of the Voting Rights Act that required states with a history of voting discrimination, including North Carolina, to pre-clear election changes with the federal government. The legislature's "eagerness to … rush through the legislative process the most restrictive voting law North Carolina has seen since the era of Jim Crow … bespeaks a certain purpose," the court said.

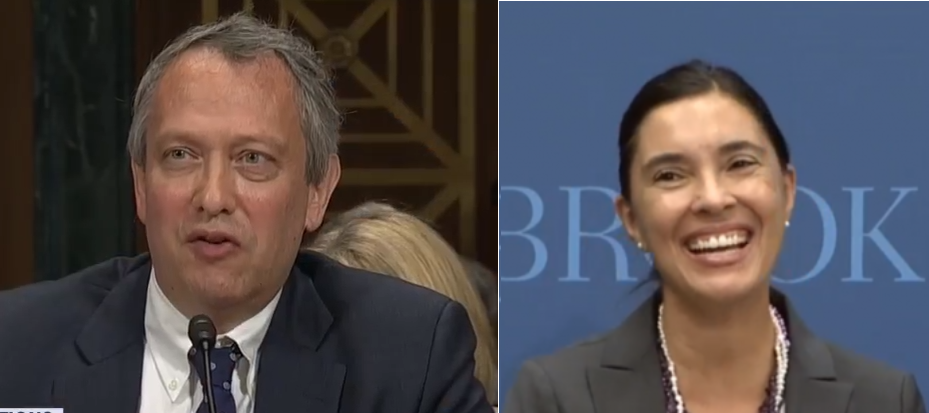

In its appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the legislature called the comparison to Jim Crow "ludicrous." Signing the appeal was the legislature's attorney, Thomas Farr, who had also advised the law's drafters and helped them sift through demographic data from the Division of Motor Vehicles showing which groups possessed certain forms of ID. A few months later, President Donald Trump nominated Farr by to be a federal judge in the Eastern District of North Carolina, part of the historically African-American Black Belt. It was Farr's third time being nominated for the position by Republican presidents since 2006, since the Senate failed to confirm him after he was twice nominated by President George W. Bush.

Last week, the Senate was poised to finally confirm Farr to the seat. But on Thursday, Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina — a Republican and the first black Southern senator since the end of Reconstruction — announced that he opposed Farr, citing the nominee's long history of involvement in voter suppression schemes.

Just weeks before Farr's nomination failed, North Carolina voters elected Earls — Farr's former opposing counsel, an African American, and a Democrat — to the state Supreme Court. She had campaigned on her experience fighting discrimination as a lawyer and on the issue of judicial independence. During her campaign, the legislature made several changes to the Supreme Court election that critics say were intended to help the incumbent Republican justice win.

Earls' victory will create a 5-2 Democratic majority on the court in 2019, when it could be hearing more legal challenges related to the state legislature's ongoing efforts to pass a new voter ID bill and restructure the state elections board. That board recently refused to certify the election of Republican Mark Harris to the 9th Congressional District due to allegations of election fraud that disenfranchised black and Native American voters in Bladen and Robeson counties. The fraud is alleged to have occurred in the Eastern District, where Farr would have presided.

Voter suppression sinks Trump's guy

Scott's decision to oppose Farr came days after the Washington Post published a decades-old U.S. Department of Justice memo that referred to Farr as leading the "ballot security" efforts of Sen. Jesse Helms' 1984 re-election campaign. Those efforts led to a settlement with the DOJ in which the Republicans agreed to stop intimidating black voters.

At his confirmation hearing, Farr faced questions about his role in Helms' voter intimidation tactics, including the mailing of dishonest flyers to more than 100,000 mostly black voters in 1990. Farr claimed he had no involvement — even though he had served as the campaign's attorney.

Rev. William Barber, a leader of the Poor People's Campaign and former head of the N.C. NAACP, strongly criticized Farr for representing the North Carolina legislature when it was sued for discriminating against black voters. Farr had defended the state's racially gerrymandered maps and its 2013 voter ID law, both of which were struck down by federal courts. Farr's legal career also included working alongside a white supremacist partner, attacking labor unions, and defending corporations accused of discrimination.

Despite the strenuous opposition of civil rights advocates and many others, Farr seemed headed for confirmation after the Senate voted 51-50 — with the vice president breaking a tie — to advance his nomination to a final vote. The only undecided senator was Scott. Questioned by reporters before the scheduled vote, Scott noted that "there are a lot of folks that can be judges" in North Carolina besides Farr.

After the nomination failed, an editorial from WRAL in Raleigh called on North Carolina's Republican senators to recommend that Trump re-nominate former N.C. Supreme Court Justice Patricia Timmons-Goodson to the seat that has now been vacant since 2005. One of two black women nominated by President Obama to the position, Timmons-Goodson would have been the first black judge in the Eastern District, where the population is nearly 30 percent black.

"It is time to end the games and assure, as the biblical verse admonishes, justice is pursued through all 44 counties in the Eastern District," the editorial said.

A win for judicial independence

There are few appellate judges in the U.S. with a resume like Earls, who has years of experience litigating civil rights cases. In a 2014 interview, Earls described her childhood in Seattle and her family's experience moving into a white neighborhood in the late 1960s. She remembers her father, who is black, experiencing discrimination.

"I thought that if I became a lawyer," she said, "I could try to help other people who were facing discrimination on the job."

After graduating from Yale Law School in 1988, Earls came to North Carolina to work with noted civil rights lawyer Julius Chambers. She handled cases involving voting rights, police shootings, and various kinds of discrimination. Earls grew frustrated, she said, because she "had the misfortune to be practicing in an era when the courts were getting increasingly conservative and the courthouse doors increasingly being closed to the claims of the people in the communities that I wanted to represent."

Earls then worked for the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, and in 2007 founded the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, which she described as "community-driven, meaning that we pursue the priorities that communities have." While Earls' work focused on voting rights, the group also litigated cases involving criminal justice, civil rights, and environmental justice.

Given her resume, it is not surprising that North Carolina's GOP-led legislature repeatedly tinkered with this year's Supreme Court election in ways that could have hindered her campaign. The legislature changed the ballot order twice so that Earls appeared at the bottom. It canceled the 2018 Supreme Court primary; a conservative secret-money group then sent mailers recruiting other Democratic attorneys to run in the general election against Earls and the incumbent Republican, whose campaign later veered into the far-right fringes.

No other Democrats joined the race, but a former Democrat filed to run shortly after switching his registration to Republican. Panicked legislators tried to retroactively change the law to require candidates to belong to a political party for 90 days before running as a member of that party, even as one Republican lawmaker made it clear that the change was intended to help the incumbent Republican. But the state courts struck down the law.

In the end, Earls won with 49.5 percent of the vote, compared to 34 percent for the incumbent Republican. "I promise to apply the law equally to everyone, no matter their race or how much money they have in their pocket," Earls said in her victory statement. "An impartial judiciary that operates without fear or favor is the cornerstone of a healthy and thriving democracy."

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.