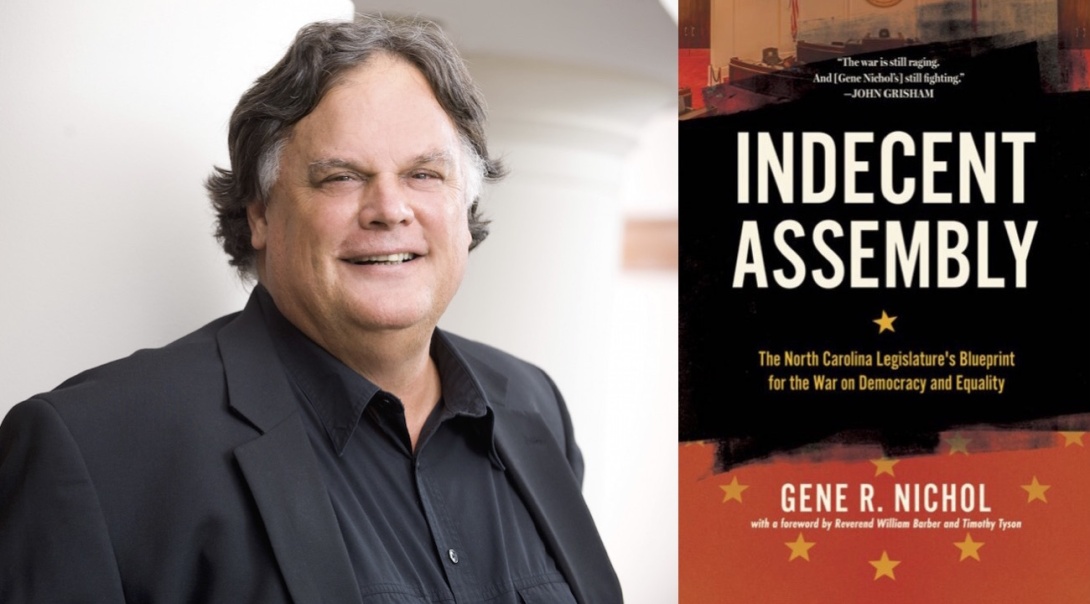

Anti-poverty crusader Gene Nichol takes on North Carolina's 'Indecent Assembly'

In his latest book, "Indecent Assembly," UNC law professor and anti-poverty scholar Gene Nichol offers lessons from North Carolina politics for these turbulent times.

Gene Nichol is not afraid of controversy. As president of the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, from 2005 to 2008, the law professor, Texas native, and former Oklahoma State University philosophy student and football player drew criticism from big donors for his decision to remove a Christian cross from permanent display in the public school's secular chapel because it could make students from other faith traditions uncomfortable. And leaders in the Virginia House of Delegates weren't happy when Nichol allowed the controversial Sex Workers' Art Show to take place on campus. "Censorship has no place at a great university," he said at the time.

After the school's Board of Visitors declined to renew his contract, Nichol resigned and was welcomed back to teach at UNC-Chapel Hill's law school, where he had previously served as dean. But it wasn't long before he found himself in the middle of another fight with state politicians — this one over poverty.

Nichol had long been an outspoken champion of the poor. As president of William & Mary, for example, one of his first official actions was to establish a financial aid program that described itself as "for women and men whose academic promise exceeds their economic means" and "who have the desire to attend a world-class university without incurring debt." That commitment continued at Chapel Hill, where he became the director of the UNC Center on Poverty, Work and Opportunity, which was created in 2005 during Nichol's tenure as the law school's dean and led for its first year by former U.S. Sen. John Edwards (D). The position took Nichol to communities across the state to learn from poor North Carolinians about their lives.

Nichol also took part in the Moral Monday movement protesting the Republican-led General Assembly's regressive agenda, and he wrote a series of op-eds for the News & Observer of Raleigh condemning legislative assaults on the poor and charging that the GOP ruled as a “white people's party.” After one column about the GOP's push for voter ID laws likened former Gov. Pat McCrory (R) to segregationist Southern governors of the Jim Crow era, the Civitas Institute, a conservative advocacy group, demanded Nichol's email correspondence, phone records, and calendars. Eventually UNC required Nichol to include a disclaimer on his op-eds stating that he doesn't speak for the school.

Then in 2014, UNC's conservative Board of Governors (BOG), elected by the GOP-controlled General Assembly, launched a review of all of the school's academic centers. In February 2015, amid raucous protest, the BOG voted to close the Poverty Center as well as the Institute for Civic Engagement at historically Black N.C. Central University and East Carolina University's Center for Biodiversity. As UNC law school dean Jack Boger said of the poverty center's closure, "The recommendation rests on no clearly discernible reason beyond a desire to stifle the outspokenness of the center's director, Gene Nichol, who continues to talk about the state's appalling poverty with unsparing candor."

But the BOG couldn't shut down Nichol. In place of the Poverty Center, the UNC law school launched the North Carolina Poverty Research Fund, which continues to provide a platform for Nichol. In 2018, he published "The Faces of Poverty in North Carolina: Stories from Our Invisible Citizens," which moves beyond statistics to tell the stories of individuals struggling in poverty. This week he released his latest book, "Indecent Assembly: The North Carolina Legislature's Blueprint for the War on Democracy and Equality," an interrogation of the state's all-white Republican legislative caucuses and their political agenda hostile to the poor, people of color, women, and LGBTQ+ people. The book's forward is by Moral Monday architect and Poor People's Campaign leader Rev. William Barber* and Timothy Tyson, senior research scholar at Duke University's Center for Documentary Studies, adjunct professor of American Studies at UNC, and author of numerous books including "The Blood of Emmett Till." Facing South's Rebekah Barber recently spoke with Nichol about the lessons his new book holds, particularly for our pandemic-afflicted times. — Sue Sturgis, Editorial Director

* * *

As you were writing your book, you had no way of knowing that we would be confronted with a global pandemic. What does "Indecent Assembly" teach us about current crisis we're facing?

Whether they are day-to-day, global, long-term, or new, challenges hit those at the bottom the hardest.

Right now, there are folks who can't afford to work by computer or by distance — they've got to work up close. There are those who can't afford not to work because they will starve if they do — and so they are more jeopardized. The pandemic is horrible across the board, but it hits those at the bottom hardest, and they tend to be those who our legislature has waged war against for a decade.

Particularly, I have been thinking about the unemployment system. In my book, I write about the massive changes the state legislature instituted in 2013, when they had supermajorities in both houses and a Republican governor. One of the first things they did was pass a bill that constituted the largest cut to unemployment compensation in American history.

They took us from the middle of the pack to having the worst set of benefits in terms of who is eligible, determining what the duration of benefits would be, and the amount of benefits.

But they didn't just change our unemployment system. There were legislators who bragged about the fact that our unemployment system was the worst in the nation. Now, because of the pandemic, over 500,000 people are having to file for unemployment. I wonder if these same legislators are still bragging about our system.

You write about how the poor in North Carolina were directly targeted by Republicans and ignored by Democrats. How do we ensure that the poor are neither targeted nor ignored?

Part of what led to the weakness and destruction of the Democratic Party in North Carolina was its willingness to turn its back on or ignore poor people. Probably since Terry Sanford (who served as the state's governor from 1961 to 1965), Democrats in North Carolina have not paid sufficient attention to those at the bottom. That's part of the tragedy of this.

But we've learned in the last decade that there is something worse than ignoring poor people, and that is choosing to punish them and target them.

I did a book a year or two ago, "The Faces of Poverty in North Carolina," to look at the actual challenges that people face. One of the things that low-income folks say regularly, repeatedly, and accurately is that the people who make the decisions have no idea about the depth of the challenges that people face in North Carolina.

And our legislators in the Republican General Assembly clearly have no idea what it means to work low-wage jobs, more than one job, over 50 hours a week — barely able or not able to support your family. They don't know those struggles. And when they think about poor people, they tend to substitute their own predispositions about what poor folks are like and act on the basis of those predispositions in ways that punish poor people.

In one chapter of my book, I write about how the General Assembly instituted drug tests for Work First recipients. They introduced and launched the pilot study with plans for the agency to report back and tell them what the results were the next year. They were thinking that the tests would explain why it was necessary.

But they were stunned because the report indicated that it was fewer than 2 percent of folks who tested positive. Some of them would not lose their benefits anyway because the benefits were going to their children.

The guy who wrote the statute said he was shocked. He assumed that everyone on welfare was using drugs. He came from a Republican caucus where everyone assumed that.

But even after learning they were wrong, they didn't end the program. I think that's because a big part of the program was to humiliate poor people.

For a long time, the plight of poor people has been missing in our democratic processes — and now its worse because we have a group of legislators who brag about how brutally they treat low-income people.

The principal thing that we need to do is reveal, and illustrate, and lift up the lives of low-income people. No one can do that better than they can through their own voices.

Until we do this, we're going to have the same set of disparities and distinctions which really belie the American dream and promise.

Can you talk about Medicaid expansion specifically? As you write in your book, we were in a crisis long before the pandemic, with thousands of people dying each year in the state because they couldn't afford health care.

I think the North Carolina General Assembly has made hundreds of deplorable decisions, but they would be hard pressed to find one as bad as this decision not to expand Medicaid.

It has cost us billions of health care dollars. It has cost us hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue. It has threatened hospitals, particularly in rural areas, but also in big urban centers. And worst of all, Harvard studies have indicated that 1,000 or more North Carolinians die each year because of this decision.

In my work, we started interviewing folks all across the state who couldn't get health care or tried to, and we used their stories to try to help explain this challenge. People were dying over the absence of very small expenditures like blood pressure medicine or insulin.

For a long time time, the plight of poor people has been missing in our democratic processes.

Now, look at this pandemic. We are already hearing that people chose not to go to the doctor until it was so late in the process that less could be done. They chose not to go because they didn't have health care — and we know that this status falls dramatically disproportionately on low-income people.

In North Carolina, 600,000 people could have health care if we would have just expanded Medicaid.

And now, millions will lose their jobs and the health care attached to it. This is an emergency of dramatic proportion.

One passage of your book states, "Donald Trump is not the United States' leading outrage — bad as he is. That indignity is reserved for how North Carolina treats poor people, especially poor children. It is villainous to be the advanced world's 'clear and constant outlier' with 'shocking' levels of child poverty amid the world's greatest plenty — a condition that we embrace." Can you speak to this passage? How do we address the systemic cruelty that long predates the election of Donald Trump?

We are the wealthiest nation on earth — the wealthiest nation in human history. The U.S. has the greatest income inequality of any society, any place on the face of the earth, at any time in human history.

In North Carolina, it's made worse than the average because we have higher levels of poverty, higher levels of child poverty, higher levels of the uninsured, higher levels of extreme poverty, and higher levels of racialized, concentrated poverty, which poses a great burden to economic mobility.

You put all these things together, and you have to explain to the world why one of the most economically vibrant states in the richest nation in human history treats its children far worse than any other advanced nation does.

As you write about in "Indecent Assembly,” between 2011 and 2018 Republicans used gerrymandering to secure a veto-proof majority in the North Carolina legislature that allowed them to pass numerous regressive policies, many of them eventually overturned by the courts. Largely because of the Moral Monday movement, North Carolina Republicans no longer have a veto-proof legislative majority. What lessons does your book offer us about organizing when power is at odds with the people?

My book is about the agenda of the legislature and what has resulted from their agenda. I think the book indicates, first of all, the power of the Moral Monday movement.

That happens when people begin to realize that their values — their very decency and commitment to their children and each other — are on the line. I think Moral Monday has taught that the most effective way to defend those values is not to rely on promises of politicians or the assumption that things are going to work out for the best, but to hit the street.

It also taught us that if you actually want to protect your way of life, you're going to have to defend it. You're going to have to engage in the streets in ways that you might have thought wouldn't be required.

* Rev. Barber is the interviewer's father.

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.