North Carolina election results show the persistence of partisan gerrymandering

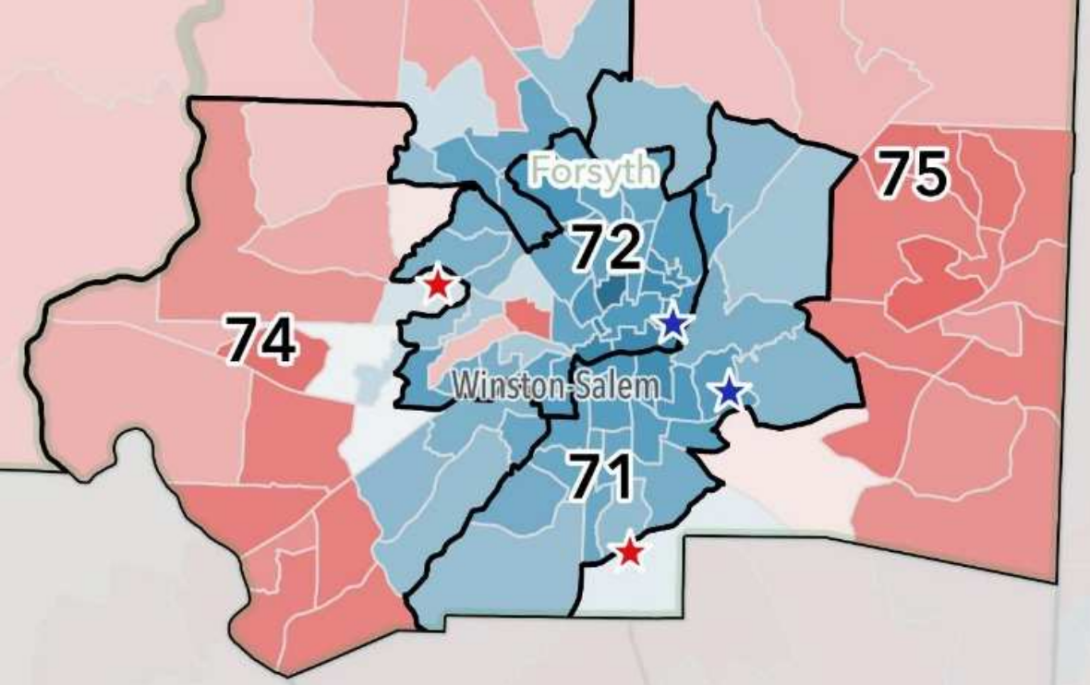

When North Carolina Republicans drew these districts last year for state House elections in Forsyth County, Common Cause claimed that they packed most Democrats into two districts, making the surrounding districts more Republican. (Map from Common Cause North Carolina.)

Democratic candidates in the past decade have often received more total votes for the North Carolina legislature, only to see the GOP maintain control. In 2019, North Carolina courts ordered the legislature to draw fairer election districts, holding out the potential for voters — not lawmakers — to decide which party would control the General Assembly. But in the 2020 election, the new districts resulted in a similar, though smaller, disparity between total votes and seats won.

In elections for the state House, Democrats got 49% of the votes but won only 42.5% of the seats, according to WRAL. More than three-quarters of the elections were landslides in which the winning margin was more than 20 percentage points. In state Senate races, Democrats got 49% of the vote and only 44% of the seats.

In 12 of the state's 13 congressional districts Democratic candidates got well over half of the total votes, but Republicans won eight of the seats. In two-thirds of those races, the margin of victory was more than 20 percentage points. A Democratic incumbent ran unopposed in one district.

In the run-up to this year's election, Democrats had hoped that the districts drawn under court order would make contests more competitive. Pope "Mac" McCorkle, a public policy professor at Duke University, said the districts have "been fixed by the state courts to a certain extent." But he noted that Democrats still had "a lot of easy wins" in the election, which suggests that mapmakers concentrated their votes in a handful of districts.

Last fall, observers and the plaintiffs in the gerrymandering case raised questions about whether the new maps still favored the GOP. But courts approved them. The case was the culmination of a decade-long legal fight over North Carolina's election districts.

Extreme gerrymandering

In the 2010 elections, Republicans won a historic number of seats in state legislatures across the country. This allowed them to control the post-census redistricting in key swing states, including North Carolina. They drew maps that packed Democrats and Black voters into a few districts. Thanks to technological innovation, the districts were more severely gerrymandered than any districts in modern history.

From 2013 to 2018 Republicans had a supermajority in both chambers of the North Carolina legislature, with enough votes to override the governor's vetoes. But in 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the legislature to redraw districts that discriminated against Black voters.

In response to the ruling, Republican state Rep. David Lewis announced that the legislature would begin redistricting and draw congressional districts that elected 10 Republicans to the 13 districts, even when Democrats got more total votes.

In June 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a lawsuit challenging the North Carolina legislature's blatant partisan gerrymandering of congressional districts. The conservative justices noted that state courts could apply state constitutions to address gerrymandering. Two months later, North Carolina courts accepted that invitation.

A three-judge panel unanimously ruled in September 2019 that extreme gerrymandering violates the state constitution, including the right to vote in "free" elections. Quoting a 1787 precedent, the judges warned that lawmakers could declare themselves "legislators of the state for life, without any further election of the people," if courts didn't step in when they exceeded their authority.

The court ordered new maps within two weeks. As Facing South reported at the time, Republican legislators began by stating that, in an effort to save time, they would use one of the 1,000 sample maps created by an expert witness in the recent trial as a "base map." Each chamber of the legislature selected a set of maps and chose one of them at random.

Common Cause North Carolina, which filed the lawsuit challenging the districts, said legislators never explained why the House and Senate pulled their base maps from different sets. "Notably, the set chosen by each chamber is the one that is relatively more favorable to Republicans," the group noted.

An analysis by Sam Wang of the Princeton Gerrymandering Project found that on average, the Senate's base map was "still biased toward Republicans." And he said the House's map included "between one-half and two-thirds of the partisan advantage that was present in the illegal gerrymander." Wang had recommended that legislators choose as their base maps the expert witness maps that didn't tilt towards one party or the other.

The newly drawn House districts, which passed the legislature along party lines, faced objections from Common Cause. The group said the House had violated several provisions of the court order, including a mandate to secure the judges' approval to hire outside consultants. It also said that House incumbents "ignored compactness in amending the maps to protect themselves."

The process was live streamed, pursuant to the court's order, and voters watched incumbents redraw the boundaries of their own districts. Common Cause argued that many revisions made the districts more similar to the ones that had just been struck down. In one district in the city of Winston-Salem, for example, Common Cause said the amendments to the base map "recreated the specific features of the prior gerrymander."

Common Cause pointed out that experts found the state House districts were "extreme partisan outliers." But the court approved them anyway. The judges said they could discern "no motive to disadvantage Democratic voters" in the changes to the Winston-Salem districts.

The House districts were in place for this year's election, and Republicans secured 57% of the seats in the chamber by getting half of the total votes.

Doing better in 2021

When it struck down the districts in fall 2019, the North Carolina court noted that "another decennial census and round of redistricting legislation" was coming up. With the census wrapping up, North Carolina is expected to gain a 14th congressional district. The state's Republican legislature will convene next year to draw new districts.

Republicans could skew the districts in their favor, as they've done before. In fact, during last year's redistricting, Republican state Sen. Paul Newton defended the practice of partisan gerrymandering and suggested that voters expected legislators to skew the districts to benefit their party. From 2013 to 2018, the North Carolina legislature gerrymandered election districts for city councils, school boards, and judges in the state's largest city.

The new districts, however, will reflect population shifts in North Carolina's fast-growing cities, and this will make it harder for Republicans to diminish the political power of urban voters through gerrymandering.

Voters in other states where legislatures draw districts should also expect GOP gerrymandering in 2021, after Republicans again did very well in state legislative elections. These voters can likely expect little protection from the U.S. Supreme Court, which punted on the issue in 2019 and now has a 6-3 conservative majority.

State courts in North Carolina and elsewhere could step in. But Wang told Facing South that he's "concerned about courts' ability to address this offense in 2021 redistricting."

In this year's North Carolina Supreme Court elections, Democrats maintained their majority. But Republicans likely gained two seats and an opportunity to win a majority in 2022.

Conservative Justice Paul Newby challenged Chief Justice Cheri Beasley, the first Black woman to hold the seat, for the leadership position; with all of the ballots counted, he appears to have won by .007% — just over 400 votes out of 5.4 million cast. Both candidates have challenged votes in some counties, and Beasley has requested a recount. On average, recounts have shifted election results by .024% in statewide elections in the past decade.

The chief justice will be in charge of assigning a three-judge panel to hear any challenge to next year's election districts. If a panel upholds districts that are skewed towards the GOP, the high court's Democratic majority may feel compelled to review the decision. The court mostly stayed out of the case last year, after the legislature didn't appeal the ruling to strike down the districts.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.