Most Southern states at high risk of partisan gerrymandering, report finds

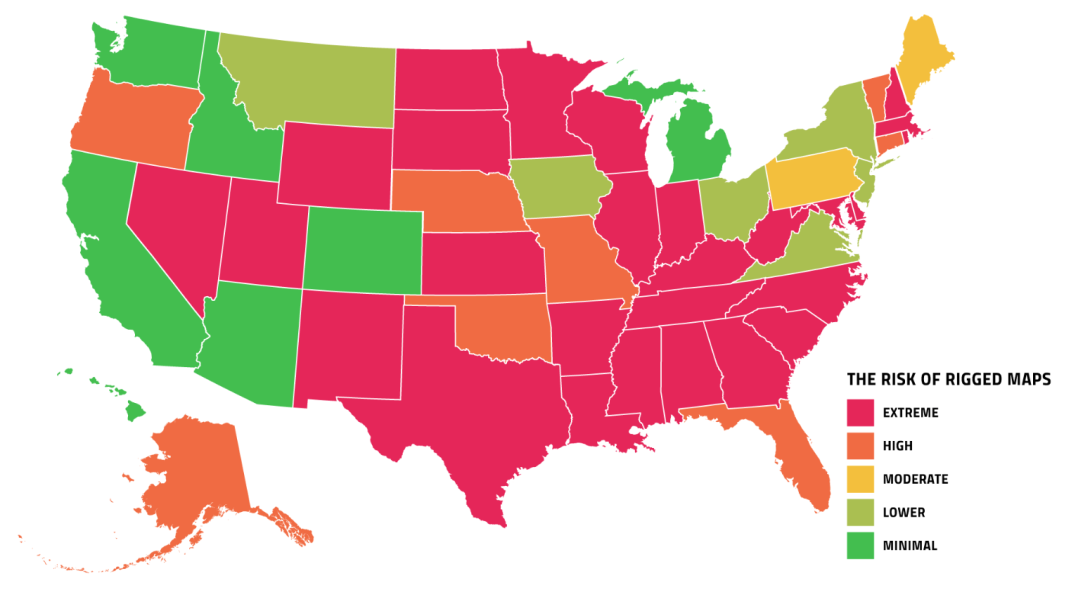

Map from the April 2021 "Gerrymandering Threat Index" published by RepresentUs.

Nearly every state in the South is at risk for partisan gerrymandering during the upcoming redistricting process, according to a report released this month by the nonprofit RepresentUs.

It found that 35 states are at an extreme or high risk of having unfair districts during this decade, and 12 of those are in the South: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia. The only Southern state where gerrymandering has a low chance of happening is Virginia, where congressional and legislative maps are now drawn by an independent commission approved by voters last year.

Gerrymandering is not new in the region, of course, but this year presents two firsts. For one thing, the redistricting process will occur without the federal preclearance that was required by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 since the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the law in its 2013 ruling in the Shelby County v. Holder case out of Alabama. And for another, the census results, which guide redistricting, have been delayed for the first time in modern U.S. history. The stakes for redistricting in the region are high, because four of the nation's political battleground states — Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas — are in the South and have seen significant demographic change in the last decade.

"Most of the growth in the South in the last decade was filled by people of color," Michael Li, senior counsel for the Brennan Center for Justice's Democracy Program, told Facing South. "In Texas about 90% of the population growth was non-white and similarly not far from that in Georgia and Florida."

"You would think there would be enclaves for additional congressional representation," continued Li, who wrote a similar report in February about what to expect during this redistricting cycle. "But that is threatening to the status quo. As a result, one thing you can expect is efforts to tap that down."

After the November elections, Republicans maintained control of most Southern legislatures, and these lawmakers now have power over how the congressional and legislative maps are drawn. In some states, such as North Carolina, governors have no power to veto or approve the maps.

"We're likely to see maps drawn to benefit the party that's in power and lock in that advantage for the next 10 years," said Jack Noland, a research manager at RepresentUs and lead writer for the organization's 2021 Gerrymandering Threat Index.

Due to weak laws against gerrymandering, the report said, "more than 188 million people will live with the threat of gerrymandering and rigged maps" for the next decade.

A history of gerrymandering

Southern states have few standards for the drawing of legislative and congressional districts besides requiring them to have equal population.

For instance, Florida law specifically bars gerrymandering, but Republicans control the legislature and thus the map-drawing process. The governor, who is currently a Republican, has no role in approving legislative maps but has the power to approve or veto congressional maps. In Georgia, another Republican-controlled battleground state that has a history of gerrymandering, the legislative and congressional maps are adopted by majority vote and approved or vetoed by the governor.

As for North Carolina, Republicans hold a majority in the legislature, and the governor, who is a Democrat, has no power to veto or approve the redistricting plans. The state has a fraught history of partisan and racial gerrymandering that has often played out in the courts for years after maps are drawn.

In 2019, according to the RepresentUs report, a superior court in North Carolina held that civil rights protections bar extreme gerrymandering in the state. But this ruling was an opinion and doesn't create a binding precedent for future cases.

Texas, despite being solidly Republican for decades, is considered a battleground state due to population growth and demographic change. The legislature also adopts the maps, which are subject to gubernatorial approval. In the 2010 cycle, Texas Republicans drew lines that were ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court, aside from one state House district that was considered an "impermissible racial gerrymander."

Besides ending the preclearance requirement, the Supreme Court's gutting of the Voting Rights Act also means that "there could be efforts to dismantle districts where communities are achieving electoral success — something that is now possible," said Li of the Brennan Center.

"Fortunately we have to redraw the maps because we have better data, but unfortunately the process to redraw the maps will open the door to kneecap the emergence of power of communities of color," Li said.

And challenges to maps are now less likely be litigated in federal courts since the Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that partisan gerrymandering is a political question that should be left to the states.

Meanwhile, the census delay could set up a shortened timeline to challenge the legality of maps in the courts. The population counts from the census are expected to be released at the end of this month, with redistricting counts to be sent to the states by the end of September. Some states with impending elections, like Virginia with its state House races coming up in November, will use the current maps.

The compressed timeline could also potentially reduce or exclude public input from the redistricting process, according to Noland of RepresentUs. Few states in the South specifically require public input on the drawing of the maps, but except for Tennessee most have allowed for comment in person and online, the report said.

According to voting rights experts, the best solution to prevent unfair map drawing is the For the People Act, federal legislation that the U.S. House of Representatives passed in March. The bill includes the most comprehensive voting rights reforms in decades and would bring transparency to redistricting by setting up independent commissions, strengthening map drawing requirements, and allowing legal redress for partisan gerrymandering.

"Broadly speaking, we see the For the People Act as the best opportunity in a generation to make real reform at the federal level," Noland said.

But the bill is currently stalled in the Senate with no Republican support. Last month, U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, a conservative Democrat, said he supports parts of the act but would want it to have bipartisan support, which is unlikely without changes to the bill.

The For the People Act has also faced criticism from some Democrats, who questioned the bill's vague language around the definition of illegal partisan gerrymandering and guidance to the judiciary, according to a Vox report.

Still, the For the People Act is important, as it could essentially ban partisan gerrymandering, Li said. And on the state level, Noland notes that getting the public involved in the redistricting process as much as possible could lead to fairer maps.

"Gerrymandering thrives on darkness," he said.

Tags

Elisha Brown

Elisha Brown is a staff writer at Facing South and a former Julian Bond Fellow. She previously worked as a news assistant at The New York Times, and her reporting has appeared in The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, and Vox.