Census results show the South's growing political power

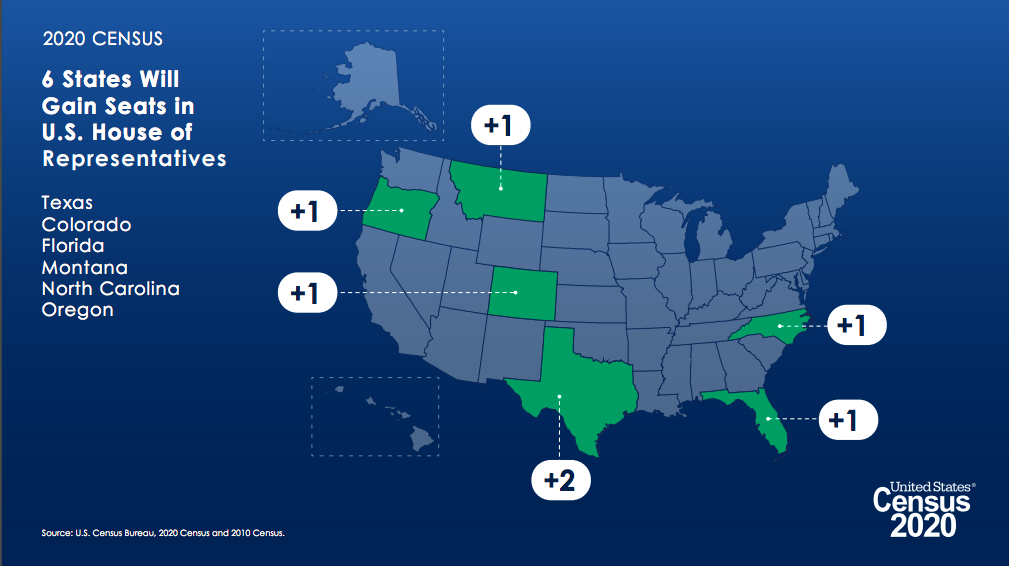

After the 2020 census, six states gained seats in the U.S. House of Representatives; four of the seven new seats are in Southern states. (Census Bureau graphic.)

The U.S. population isn't growing as fast as experts thought, and fewer people appear to be moving to Southern states like Florida and Texas that have been top destinations in recent decades.

Yet while population growth and mobility have slowed nationwide, the South remains the country's fastest-growing region, continuing a shift in the nation's political gravity to Southern states.

These are among the trends revealed in the initial batch of 2020 census data released last week. After missing its Dec. 31, 2020, deadline, the embattled Census Bureau disclosed statewide population totals in April that will be used for congressional reapportionment, which determines whether states gain or lose seats in the U.S. House.

While the nation's declining growth rate — the biggest drop since the Great Depression — surprised many demographers, the 2020 figures solidified the South's status as the region with the country's most dynamic population. The 13 Southern states grew 10.5% since 2010, accounting for nearly half of the country's overall population increase. Facing South defines the region as including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

This growth translates into greater political clout for the South. Texas will gain two additional congressional seats, and Florida and North Carolina one each, mostly at the expense of states in the Northeast and Midwest. West Virginia, which had the most dramatic rate of population decline nationally, will lose a House representative, bringing the South's net gain in congressional seats to three.

These gains reflect a decades-long shift in the nation's political power to the South. Since 1990, an influx of newcomers from other states and countries have led Southern states to gain 15 congressional seats and Electoral College votes for president — more than half of those in Texas alone.

While significant, the South's gains during the 2020 census were smaller than many had expected. As recently as 2019, demographers had projected Texas would gain three seats, and Florida two.

"Some of the places we thought were growing quite quickly, according to the new census numbers, actually did not grow quite as quickly as we thought," said Rebecca Tippett, director of Carolina Demography at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. "There's still growth more heavily concentrated in the South, but just not at the pace we had anticipated."

The South's undercount risks

Because the data released on April 26 included only statewide totals, demographers have few clues to sift through to understand why states like Florida and Texas missed their growth projections.

"Right now, what we know is how many people live in Texas and Florida," said Michael Li, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice. "We don't know where in the state they live. We don't know anything about them, including key information like their age, race, and ethnicity, so we don't know exactly what is causing this."

Heading into the 2020 census, several factors put the South at higher risk of an undercount. For one, Southern states have a disproportionate share of what the U.S. Census Bureau identifies as "hard-to-count" populations, or groups that have historically been undercounted in the decennial census. These include African American communities, low-income and isolated rural residents, and Asian and Latinx immigrants.

Many Southern states and localities were also slow to invest in census outreach. As late as August 2019, Facing South reported that 10 states in the South had neglected to fund projects to encourage hard-to-count communities to fill out census forms, causing localities and nonprofits to scramble to fill the vacuum.

Texas spent $15 million on a last-minute ad campaign in September 2020, and Florida never earmarked funds for the census count. Both states had response rates below the national average, while Alabama — which did invest in census outreach — had a higher population count than expected, and avoided losing a U.S. House seat.

Another potential roadblock during the census count was the Trump administration's failed effort to add a citizenship question to the survey. Immigrants from Asia and Latin America accounted for a large share of the population boom that Southern states registered in the 2010 census — about two-thirds of the gains in Florida, Texas, and other states. While the Trump administration abandoned its quest for the citizenship question after a July 2019 defeat in the U.S. Supreme Court, demographers and others feared that lingering confusion and distrust about the issue would depress census participation.

"The damage may have been done the minute they announced that they were trying to add a citizenship question to the census because it created fear in immigrant communities," Li said. "Once the fear is out there, it's really hard to put things back in the bottle."

New maps and growing clout

More definitive analyses of the 2020 census can be expected as detailed information rolls out from the Census Bureau later this year. The redistricting data will be released by the end of September, and Southern states — which are considered at high risk for partisan gerrymandering — will begin the fraught process of drawing new state and congressional maps.

For now, the big takeaway for the 2020 census data is that the South, while not growing as fast as some had predicted, continues to expand its political clout and ability to shape the national agenda.

"The decades long-trend of power shifting away from the Midwest and the Northeast and to the South and the West is continuing," Li said. "By all accounts, the South was the fastest growing region in the country."

Tags

Elisha Brown

Elisha Brown is a staff writer at Facing South and a former Julian Bond Fellow. She previously worked as a news assistant at The New York Times, and her reporting has appeared in The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, and Vox.

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.