Ending harsh felony disenfranchisement laws in the South

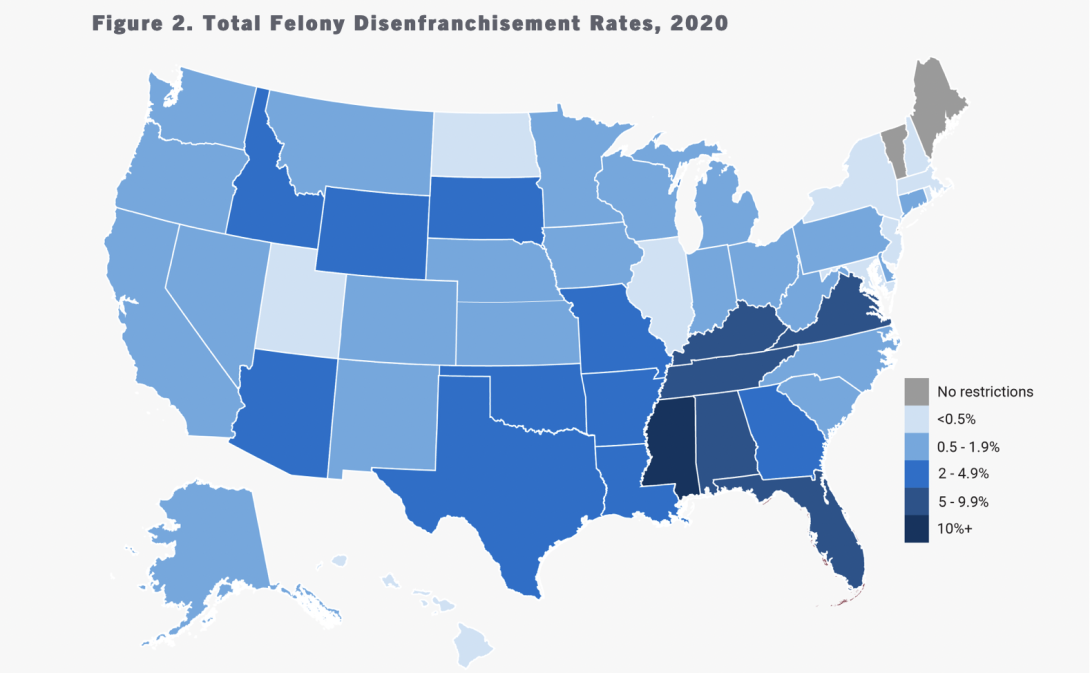

Southern states have some of the nation's highest felony disenfranchisement rates, but organizing efforts are underway to bring those numbers down. (Map from "Locked Out 2020" by the Sentencing Project.)

A lawsuit seeking to restore voting rights to North Carolinians with felony convictions faced a setback on Sept. 3 when the state Court of Appeals stayed a lower court's August ruling that would have allowed people on probation or parole to register while the case moved forward. The lower court's decision would have immediately affected about 56,000 people who have lost the right to vote due to the state's felony disenfranchisement law.

The plaintiffs then turned to the state Supreme Court, which on Sept. 10 rejected their motion to allow probationers and parolees to continue to register while the case makes its way through the legal system. But it did allow those who registered between Aug. 23 and Sept. 3 to stay on the rolls.

Forward Justice — a legal services advocacy group based in Durham that serves as co-counsel on the case, which was filed by the Community Success Initiative, the North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, Justice Served NC, and Wash Away Unemployment as well as individual plaintiffs — said in a press release that it was disappointed the Supreme Court didn't fully reinstate the total rights restoration injunction. But it's pleased that those who already registered can remain so.

"We are now a step closer to our goal, and even in the face of this temporary delay of full justice, we are celebrating," the group said. "We remain committed to the vision of an equal democracy, untainted by laws illegally designed to disenfranchise Black people in this state."

Filed in November 2019, Community Success Initiative v. Moore makes the case that North Carolina's felon disenfranchisement laws — initially written in the late 1800s as white-supremacist lawmakers sought to regain political power lost during Reconstruction — are intrinsically racist.

"Our argument all along has been that the disenfranchisement statute traces back to that 1870s period, which is when disenfranchisement in North Carolina was first imposed for all people with felony convictions and when, for the first time, North Carolina extended disenfranchisement for people with felony convictions beyond the date of their incarceration," said Elisabeth Theodore, a lawyer at the Washington, D.C.-based law firm Arnold & Porter, another co-counsel in the case.

Though North Carolina tweaked its felony disenfranchisement law in the early 1970s, it continued to bar voting rights for people until they completed probation, parole, or post-release supervision — what Theodore calls the law's "racist taint." According to 2018 data cited in the lawsuit, Black people accounted for 20% of North Carolina's voting age population but 40% of people who lost their voting rights after serving time in the state.

Virginia leads the way

Had the lower court's ruling stood, North Carolina would have been the first state in the South to automatically restore voting rights to people after they complete their prison or jail sentences. But despite the North Carolina appellate rulings, the wider movement to re-enfranchise people with felony convictions is making progress across the region, which has some of the nation's most draconian restrictions.

The movement won a key victory in Virginia in 2013, when then-Gov. Robert McDonnell, a Republican, announced a plan to restore the voting rights of thousands of residents with nonviolent felony convictions. His successor, Democrat Terry McAuliffe, went on to restore the voting rights of about 173,000 people with felony convictions after they completed their sentences, as the Washington Post reported. Current Gov. Ralph Northam, a Democrat, has continued those efforts; by March of this year, he had restored the voting rights of about 69,000 people with felony convictions after they finished their time in prison, according to the Post.

The Virginia Constitution currently disenfranchises all people convicted of felonies unless their rights are restored by the governor. But this year the Virginia General Assembly gave preliminary approval to a proposed 2022 constitutional amendment that would automatically restore the voting rights of people after they leave prison, even if still on probation or parole. Lawmakers must pass the amendment again next year, and it needs the approval of a simple majority of Virginia voters to become law.

Along with Virginia, Kentucky is among the few states whose constitutions permanently disenfranchise people convicted of felonies but allow governors to restore those rights individually. After his election in December 2019, Gov. Andy Beshear (D) issued an executive order that restored voting rights for over 140,000 people with felony convictions who had finished probation and parole.

"My faith teaches me to treat others with dignity and respect. My faith also teaches forgiveness and that is why I am restoring voting rights to … Kentuckians who have done wrong in the past, but are doing right now," Beshear said at the time. "I want to lift up all of our families and I believe we have a moral responsibility to protect and expand the right to vote."

Due to Beshear's initiative, over 170,000 Kentuckians regained the right to vote as of the start of this year, the Louisville Courier-Journal reported. But recent data from The Sentencing Project shows the state still has one of the nation's highest disenfranchisement rates, as well as one of the highest rates of disenfranchising African Americans specifically.

In January of this year, a bipartisan group of Kentucky lawmakers introduced a bill proposing a constitutional amendment to automatically restore voting rights for people with felony convictions after the completion of prison, parole, and probation, but it died in committee.

In Louisiana, the legislature passed a law in 2019 restoring voting rights for 36,000 people on probation or parole who had not been incarcerated for the previous five years. Earlier this year it passed another law allowing some people convicted of felonies to serve on juries — a measure that had the backing of the Louisiana District Attorneys Association.

Meeting GOP hostility

Before the 2020 presidential election, the Georgia Secretary of State's office posted a notice on its website clarifying that people convicted of felonies who had finished their sentence but had yet to pay outstanding fees, other than fines related to their court sentences, can register to vote. In January, a group of Democrats in the Georgia House of Representatives filed a bill to add an amendment to the state constitution that would make it easier for people who have been incarcerated to vote, but the legislation hasn't moved forward.

In 2016, the Alabama legislature eased the voting rights restoration process for persons who completed sentences for felonies other than those the state deemed crimes of "moral turpitude." In response to complaints that category was vague, it passed the Moral Turpitude Act the following year defining what exactly those crimes are. There are now about a dozen crimes in the state that require the restoration of voting rights through pardons, including murder, rape, and child pornography, while treason and impeachment carry a permanent loss of voting rights, according to the American Civil Liberties Union of Alabama.

There have been problems getting the word out about the new Alabama law, however: A 2020 investigation by AL.com revealed a lack of awareness about the law by both the public and county officials, who as a consequence had wrongly barred some eligible people from voting.

In Mississippi, there are currently 22 crimes — ranging from arson and armed robbery to writing a bad check and shoplifting — that prevent people from voting unless they get a governor's pardon or the legislature's approval. Earlier this year, the Mississippi Poor People's Campaign, the Mississippi Prison Reform Coalition, and the People's Advocacy Institute announced they plan to file paperwork for a ballot initiative to automatically restore convicted people's voting rights after they finish serving their sentences.

But the experience in Florida shows how such ballot initiatives can be undermined by a hostile state government. In 2018, the state's voters approved Amendment 4, which aimed to restore voting rights to about 1.4 million Floridians with felony convictions after they finished probation or parole. But the amendment was met with animosity from Gov. Ron DeSantis and his Republican allies in the state legislature, who controversially claimed that it required implementing legislation before it could take effect.

They crafted and passed a bill that required people with felony convictions to complete "all terms" of their sentence — including full payment of restitution, fines, fees, or any associated costs. The measure was challenged for effectively imposing unconstitutional poll taxes, but last year the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled to let it stand. A study by a University of Florida political science professor found that about four out of five people who qualified under Amendment 4 owed some sort of court-imposed fees, fines, or restitution.

The Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, a group that led the fight for Amendment 4, estimated in the run-up to last year's election that over 67,000 people have registered to vote because of the new policy. Meanwhile, the group continues to raise funds to help returning citizens pay back their debts and reports it is currently $2.3 million away from its $10 million goal.

Tags

Elisha Brown

Elisha Brown is a staff writer at Facing South and a former Julian Bond Fellow. She previously worked as a news assistant at The New York Times, and her reporting has appeared in The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, and Vox.