Supreme Court could give legislatures unprecedented control over elections

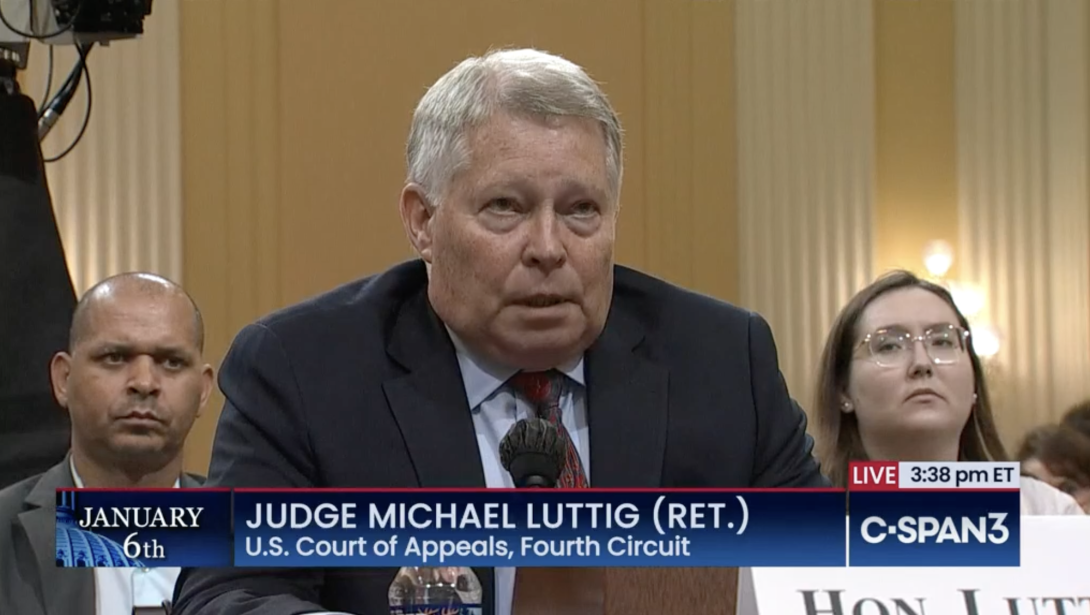

Retired Judge Michael Luttig, who served on the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Virginia, testified on June 18 before the House select committee investigating former President Donald Trump's attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. Luttig, a Republican, warned that the independent state legislature theory being promoted by Trump backers is part of a plan to "overturn the 2024 election if Trump or his anointed successor loses." (Still from C-SPAN video.)

The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear a case out of North Carolina that could give state legislatures much broader authority over elections for Congress and president. For the first time in history, state courts wouldn't be able to strike down unconstitutional congressional districts or state laws governing federal elections.

The ruling could even pave the way for a legislature to overturn the presidential election results in its state — as proponents of the theory attempted to get legislatures to do after former President Donald Trump's 2020 election loss to Democrat Joe Biden.

Back in February, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down congressional districts that the Republican-controlled legislature gerrymandered to benefit GOP candidates. In a party-line 4-3 decision, the court's Democratic justices held that "our constitution's Declaration of Rights guarantees the equal power of each person's voice in our government through voting in elections that matter." High courts in other states have struck down election districts for the same reason, as these courts have traditionally had the final say on interpreting state constitutions.

But North Carolina House Speaker Tim Moore and Senate President Phil Berger, the defendants in the case, immediately appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Three right-wing justices wanted to hear the case right away and overturn the state Supreme Court's ruling, with Justice Samuel Alito writing in a dissent that "there must be some limit on the authority of state courts to countermand actions taken by state legislatures when they are prescribing rules for the conduct of federal elections. I think it is likely that the applicants would succeed in showing that the North Carolina Supreme Court exceeded those limits." However, Justice Brett Kavanaugh didn't want to act through the court's so-called "shadow docket," which includes emergency orders that cannot wait for full argument. So on June 30, the justices announced that they would hear the case in their next term, which starts in October.

The appeal relies on the "independent state legislature theory," a literal reading of two provisions of the U.S. Constitution that give power to regulate federal elections to "legislatures." Courts have always interpreted these provisions to mean that state laws — including state constitutions — govern elections. But some Republicans now argue they mean that, while Congress can override laws that govern congressional elections and state courts can strike down laws governing state and local elections, state courts can't strike down state laws governing federal elections.

In a recent op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, voting rights lawyer Eliza Sweren-Becker of the Brennan Center for Justice said the theory "has no legal or historic validity — it is a fever dream of partisan activists who are desperate to find some pretext to empower certain state legislatures for their political advantage." The Brennan Center also notes that the theory could even bar legislatures from delegating authority to establish election rules to governors or election officials.

The founders understood that legislatures were bound by state constitutions, which were interpreted by courts in the respective states. In North Carolina, the power of judicial review was established in 1787, before the U.S. Constitution was even ratified.

In recent decades, however, some right-wing jurists have pushed the theory that state courts can't strike down state laws related to federal elections — an idea that emerged in a landmark elections case. In Bush v. Gore, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively overturned the Florida Supreme Court's order to continue recounting ballots in the 2000 presidential election. Three conservative justices on the court at the time, including Clarence Thomas, argued that their intervention was justified because the state court had "departed from the legislative scheme" governing presidential races.

State judges can't "wholly change" the state laws at issue, they claimed. The argument didn't attract much notice at the time.

An amendment fix?

Two decades later, former President Trump and his lawyers invoked the independent state legislature theory in federal appeals from state court rulings in lawsuits over expanded access to voting by mail during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though the high court rejected those appeals, Justices Neil Gorsuch, Alito, Kavanaugh, and Thomas dissented, suggesting that they agreed with the argument. Trump's team also relied on the theory when, citing false claims of fraud, they tried to convince state legislators to overturn the election results and award their state's Electoral College delegates to Trump.

When the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down congressional election districts earlier this year, it noted that the independent state legislature theory is a departure from nearly 100 years of U.S. Supreme Court precedents. "It is also repugnant to the sovereignty of states, the authority of state constitutions, and the independence of state courts, and would produce absurd and dangerous consequences," the ruling said. The theory would be a new way of thinking for the U.S. Supreme Court, because when it threw out a North Carolina lawsuit over partisan gerrymandered congressional districts in 2019, all five conservative justices signed a ruling that specifically said state courts could continue to address the question.

How the theory would play out in North Carolina is difficult to envision. Even if legislatures were given sole authority over elections, North Carolina's has authorized state courts to strike down unconstitutional election districts — state and federal — through two statutes that outline the procedure for judicial intervention in redistricting.

The Republican leadership's appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court limits its argument to cases in which state courts apply what it characterizes as "vague" provisions, such as the right to free elections contained in the North Carolina Constitution. This interpretation would presumably allow state courts to continue striking down districts for violating specific provisions, such as Florida's constitutional amendment that explicitly requires fair election districts. But there's no basis for this distinction in the U.S. Constitution.

A broad version of the theory would allow legislatures to overturn the results of an election in their state. Retired Judge Michael Luttig, a Republican who served on the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Virginia and recently testified before the House select committee investigating Trump's attempt to overturn the election on Jan. 6, 2021, described the independent state legislature theory as part of a plan to "overturn the 2024 election if Trump or his anointed successor loses again in the next quadrennial contest." Supporters of the "Big Lie" that the 2020 presidential election was stolen are currently running for office across the country.

University of Kentucky law professor Joshua Douglas is an expert in election law and author of the book "Vote for US: How to Take Back Our Elections and Change the Future of Voting." In a recent law review article titled "Undue Deference to States in the 2020 Election Litigation," he calls for countering the independent state legislature theory with new voting rights legislation and a constitutional amendment that he says "would recognize explicitly the fundamental right to vote as a vital feature of our democratic structure."

He specifically cites an amendment introduced in 2020 by Democratic U.S. Sen. Richard Durbin of Illinois that would provide an affirmative right to vote, require that any efforts to limit the fundamental right to vote be subject to the strictest level of court review, ensure states could no longer prevent Americans from voting due to a criminal conviction, and provide that Congress has irrefutable authority to protect the right to vote through legislation. Douglas recommends that Congress strengthen the resolution's language to ensure that legislatures don't have unfettered authority over their states' presidential elections. The proposal, which has eight sponsors, has seen no further action.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.