NC students organize against voter suppression

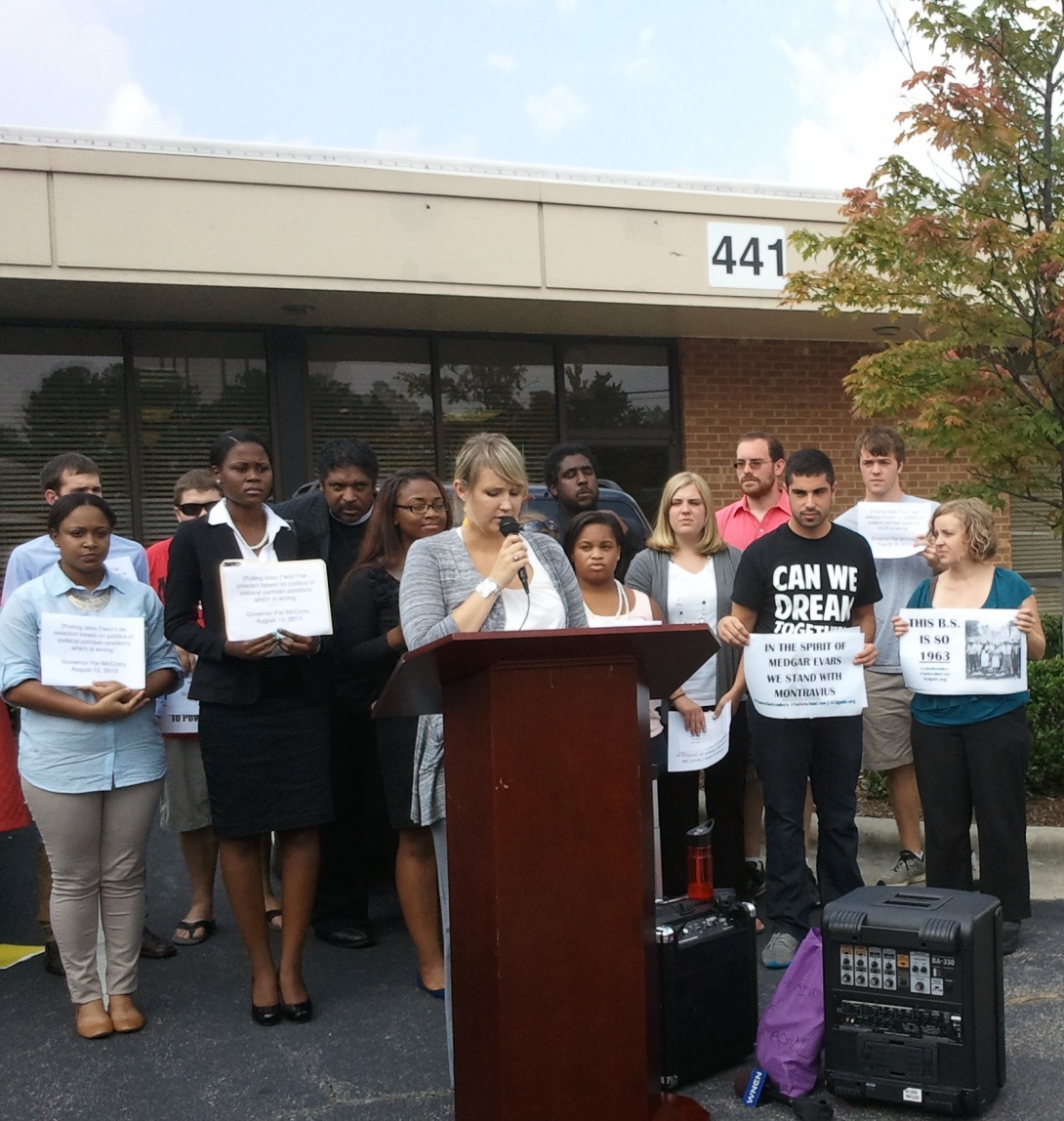

Students and their allies spoke at a press conference outside the N.C. State Board of Elections before a Sept. 3 hearing on the challenge to Elizabeth City State University student Montravias King's bid for a local city council seat. Bryan Perlmutter is third from right in the black T-shirt, holding a sign that says, "In the spirit of Medgar Evers, we stand with Montravias." (Photo by Sue Sturgis.)

The "vote truthers" trolling for fraud in North Carolina -- groups like the N.C. Voter Integrity Project that watch and challenge voters -- may now themselves become the watched.

Bryan Perlmutter, a recent graduate of N.C. State University in Raleigh, is leading a student-run initiative called the N.C. Vote Defenders that will train and organize North Carolina college students to protect voters -- especially college students and people of color -- from overzealous poll watchers. The effort comes in response to the state's controversial new Voter Information Verification Act, which contains provisions that expand the powers of amateur poll observers -- activities that have hazardous racial histories in North Carolina and beyond.

The effort also comes as students at historically black Elizabeth City State University and other schools have suffered an onslaught against their voting rights that has included being purged from voting rolls, losing on-campus early voting sites, and having their residency challenged -- a problem that almost blocked ECSU student Montravias King from running for city council.

But college students haven't been taking these attacks sitting down. Instead, they've been sitting in.

One of the legacies of the Moral Monday protests at the state legislature is that they have galvanized citizens from all walks of life, including many in higher learning, to stage sit-ins and pray-ins against unjust policies. Perlmutter is one of those inspired by the NAACP-led protests and was one of the first arrested when they kicked off in April. Before that, he organized N.C. State students around tuition hikes and school budget cuts. But it was the voting rights attacks this year that moved Perlmutter to pivot from the business administration degree he obtained in May to political organizing.

"Students who may not consider themselves organizers or activists find themselves now asking, 'Why are they doing this to us? Why do they they want to make it harder for us to vote?'" said Perlmutter. "So we want to be on the ground to give them outlets and make sure people going to the polls can vote -- and also educate ourselves on our surrounding communities in the process."

He's working with the Election Protection hotline group to help train the Vote Defenders, and he is also seeking help from civil rights groups. Right now, the strategy is to target five schools across the state -- N.C. State, ECSU, Appalachian State, Winston-Salem State, and UNC-Charlotte -- and deploy Defenders there to record and report any voter intimidation. He plans to work with HBCU and non-HBCU students alike and sees cause for a natural coalition between them.

"I think that times like these are when we can build unity under common identity features and look at who is trying to maintain power and find out the motives behind these attacks," said Perlmutter. "What's happening right now is horrible for North Carolina, but it creates opportunities to build bridges among distant groups in the midst of these attacks."

The Vote Defenders project is one of several initiatives to stand up for student voting rights in North Carolina. The state NAACP conference is working with the Durham, N.C.-based Southern Coalition for Social Justice to defend students who face voting rights challenges. The Youth and College Division of the N.C. NAACP is leading a college tour to raise awareness around election protection. It is also organizing a march for voting rights on Gov. Pat McCrory's (R) mansion on Sept. 16 -- the 50th anniversary of the bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala.

This work is not happening in a historical vacuum. Black college students with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee -- launched in 1960 on the campus of historically black Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C. -- led nonviolent direct actions and sit-ins to protest racist voting and segregation policies. Student-initiated demonstrations also occurred in the early 1940s, led by historically black Howard University students with the NAACP's backing.

"In response to the [World War II] draft, segregation in [Washington, D.C.], and in the military, the poll-tax, the ideal of preserving democracy, and the ideal that 'they' had to do something to improve their lot, a small group of Howard students began to act," wrote history professor Flora Bryant Brown in a fall 2000 article on black student organizing for the Journal of Negro History.

Brown is now special assistant to the chancellor of Elizabeth City State University. Contacted about voting rights attacks on ECSU students, she declined to comment.

Those Howard University students were organizing against the extreme racist D.C. government run by Theodore Bilbo, a former governor of Mississippi and Ku Klux Klan member. In his book “Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time," Ira Katznelson writes that Bilbo once recalled a meeting with D.C. black civil rights leaders in less than fond terms: "Some niggers came to see me one time in Washington to try to get the right to vote there," said Bilbo. "I told [them] that the nigger would never vote in Washington. Hell, if we give 'em the right to vote up there, half the niggers in the South will move into Washington and we'll have a black Government."

Of course, D.C. now has a black mayor, and there are multiple African Americans representing North Carolina in the legislature and Congress. And in 2008, North Carolina voters elected to put a black president to the White House, with the youth vote key to his win there. Could this explain why conservatives in the state are now trying to make it harder to vote for black students and their peers?

The apparent answer to that question is why, at least for now, Perlmutter is opting not to take his business degree to corporate America.

"This is where I'm from, this is where I grew up," said Perlmutter, "and I see a sense of urgency, so my plans for the future are to stay involved in this fight."