Are environmentalists pushing a risky alternative for coal ash disposal?

The recent failure of a pipe under a coal ash impoundment at a Duke Energy power plant in North Carolina sent millions of gallons of pollution into the Dan River and sparked public debate about the need for safer ways of storing coal ash that won't imperil drinking water supplies.

Nowadays, coal ash -- the toxin-laden waste left over after burning coal to produce electricity -- is typically stored wet in massive impoundments on the sites of power plants. The plants and their ash impoundments are usually located on rivers or other water bodies, since the plants need a water source to make steam that spins turbines to drive a generator. The impoundments not only threaten nearby waterways; because they are unlined, they also allow toxins from the coal ash seep into the earth and contaminate groundwater. To date, environmentalists have documented more than 200 coal ash damage cases in 37 states, with many involving groundwater contamination.

Environmental advocates have long called for coal ash to be removed from these impoundments, dried out, and stored in double-lined landfills. This is also the storage method called for in the draft coal ash rule that the Environmental Protection Agency released back in 2010, and which it is scheduled to finalize by the end of this year.

But this week, the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League, a North Carolina-based environmental watchdog group, released a report that sounds the alarm about the risks of the landfill approach, noting that all liners eventually leak -- which is why most manufacturers offer only a five-year warranty. BREDL called instead for what it says is a much safer storage method for coal ash: solidifying it with concrete and storing it in aboveground vaults on power plant property.

"Duke's coal ash should be classified as hazardous waste," says BREDL Executive Director Louis Zeller. "It contains cadmium, lead, chromium, arsenic and radioactive isotopes and cannot be landfilled safely no matter how many plastic liners."

The disposal method BREDL is recommending is known as the "saltstone process" and was developed by the U.S. Department of Energy for handling hazardous waste at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina. Here's how BREDL's report describes it:

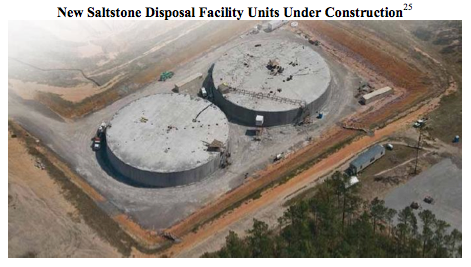

Production byproducts from decades of defense operations are stored in dozens of million-gallon tanks at SRS. The wastes are a witch's brew of toxic compounds including heavy metals and radioactive compounds. After radioactive substances are removed, the remaining mixture is transferred to the Saltstone Production Facility and mixed with cement, slag, and fly ash to form a grout which is then disposed of in the Saltstone Disposal Facility.

The grout mixture, or slurry, is mechanically pumped into concrete disposal vaults that make up the Saltstone Disposal Facility. The mixture solidifies into a non-hazardous, low-radioactive saltstone waste. When a concrete vault is filled, it is capped with clean concrete to isolate it from the environment. Final closure of the area consists of covering the vaults with engineered closure caps, backfilling with earth and seeding to control water infiltration and erosion.

Monitoring wells near the edge of the disposal site ensure groundwater is not being contaminated. BREDL reports that tests done by the DOE have found that the saltstone waste disposal technique does not release pollution to the environment above federal drinking water standards.

And by keeping the waste on the power plant property, the saltstone approach avoids the kind of environmental injustice that occurred in the wake of the 2008 coal ash spill from the Tennessee Valley Authority's Kingston plant into the Clinch and Emory rivers in eastern Tennessee.

After TVA dredged up the spilled coal ash, the Environmental Protection Agency allowed it to ship the waste from the largely white, middle-class community in Roane County, Tenn. to the Arrowhead Landfill near Uniontown in Perry County, Ala., where 88 percent of residents are African-American and almost half live in poverty.

Neighbors of the Arrowhead facility -- some living as close as 100 feet away -- soon began complaining of unusual runoff and sickening smells. John Wathen, the Hurricane Creekkeeper based in Tuscaloosa, Ala., did independent monitoring and documented dangerously high levels of arsenic in landfill runoff collecting in roadside ditches. He also observed coal ash falling from overloaded trucks and spilling along the roads and into a nearby creek.

In December 2013, Earthjustice, a public-interest law firm, notified the EPA's Office of Civil Rights that it would represent six Alabama residents in a civil rights complaint under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits recipients of federal funds from taking actions that have unjustified disproportionate effects on the basis of race. The complaint accuses the Alabama Department of Environmental Management, which gets federal funds, of reissuing and modifying the landfill's permit without proper public health protections.

BREDL and its allies do not want to see a similar scenario play out with the coal ash spilled from Duke Energy's Dan River plant, or with the coal ash stored in impoundments at other power plants across the state.

"Duke Energy's mismanagement of coal ash has now expanded into an enormous toxic waste challenge," says Jim Warren, executive director of the environmental group NC WARN, which joined BREDL in calling for landfilling alternatives. "State history makes clear that there are no quick, easy fixes, and the solution must provide justice for communities currently impacted -- and for those who might be targeted to have the toxic waste dumped on them."

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.