Art Pope vs. cooperative economics: Who will save Raleigh's food desert?

Art Pope, a prominent donor to conservative causes and close ally to the influential Koch brothers, steps down as North Carolina's budget director this week, a move that frees him to get involved in politics again in an important election year. It will also allow him to devote more time to his work as CEO of the Variety Wholesalers discount retail chain -- and to a controversial new business deal the company is undertaking in North Carolina's capital city.

The company recently announced that it's opening a grocery store in the historically African-American neighborhood of Southeast Raleigh, which has been officially designated a food desert. Pope, who lives in Raleigh's upscale Country Club Hills neighborhood, said the store is "a way to serve our community." Coming amid grassroots efforts to address the local food access problem, Pope's venture has been welcomed by some local leaders but criticized by others who question whether it will be good for the community's well-being over the long term.

"He's promoting conservative values that hurt poor people," the Rev. Earl Johnson, head of the Raleigh-Wake Citizens Association, the area's oldest, nonpartisan African-American political group, recently told The News & Observer. "I'm encouraging people in this community not to support this store."

The controversy began unfolding in July when Variety Realty -- the property arm of Pope's Variety Wholesalers discount retail business and one of the largest privately owned companies in the U.S. -- bought a vacant Kroger grocery store in Southeast Raleigh with plans to open a Roses variety store and a separate grocery. Based in Henderson, North Carolina, Variety Wholesalers owns the Roses, Maxway, Super 10, Bargain Town, Bill's Dollar Store, and Super Dollar chains, and entered the grocery business two years ago when it opened a combination Roses and grocery in Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

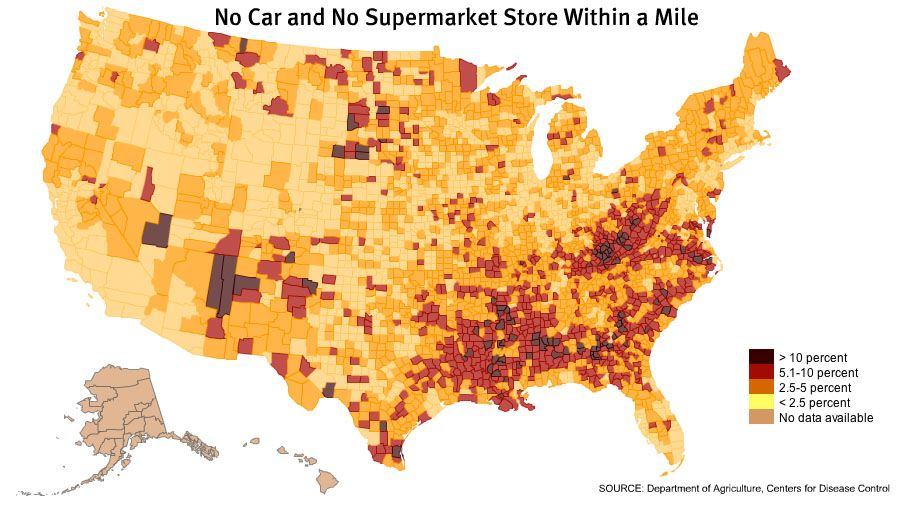

Back in November 2012, Ohio-based Kroger announced it was closing two stores in Southeast Raleigh. City and community leaders expressed alarm since the area was already recognized as a so-called "food desert" by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which defines a food desert as "a census tract with a substantial share of residents who live in low-income areas that have low levels of access to a grocery store or healthy, affordable food retail outlet." More than 23 million people across the U.S. live in food deserts, and, as this 2011 map by Slate shows, they are an especially serious problem in the Southeast and Appalachia (click on map to see a larger version).

The month after the Raleigh Kroger closings were announced, more than 100 people gathered at a downtown church to discuss solutions to the community's food access problems. Following that meeting, various groups, nonprofits and churches sprung into action to help improve local residents' access to healthy food.

This spring, two Raleigh churches -- Ship of Zion Ministries and Hope Community Church -- with assistance from a team leader at a local Whole Foods store launched the nonprofit Galley Grocery Store in Southeast Raleigh. The store is stocked with fruits, vegetables, and other healthy staples, and it does not sell alcohol or tobacco.

Also this spring, the USDA-funded Voices Into Action: The Families, Food and Health Project based at N.C. State University in Raleigh awarded small grants to groups working on addressing the area's food desert problem. Recipients included the Alliance Medical Ministry, which has a community garden in the area that provides healthy food to patients and community members; Grocers on Wheels, a mobile produce market that makes stops throughout the neighborhood; and Fertile Ground Food Cooperative, which is in the planning stages of opening a food co-op in Southeast Raleigh.

Last year, the community's access to quality food got a boost when Carlie C's IGA, a North Carolina-based grocery chain, opened for business in one of the two shuttered Krogers. Meanwhile, the City of Raleigh allowed a temporary farmer's market in the parking lot of the empty store.

Then in May of this year, Kroger sold the vacant grocery for almost $2.7 million to a group of out-of-state investors. Two months later, the investor group sold the property to Pope's company for $2.68 million -- less than half its assessed tax value of $5.9 million.

'Not many advancement opportunities'

Opening a store in Southeast Raleigh fits Variety Wholesalers' location strategy to a T. Until recently, the company's website said it targeted communities with a "minimum 25% African-American population within 5 miles" and "median household income of $40,000 or less." The website now says the company looks for locations "in under-served markets" with a median household income of $45,000 or less. Variety Wholesalers already operates a Maxway store less than a mile away from the former Kroger. The census tract where Pope's future grocery is located is 81 percent African-American with a median household income of less than $22,000.

The community had mixed reaction's to Pope's purchase. Some local African-American elected officials and other community leaders attended a news conference in front of the empty Kroger to express support for Pope's plans.

"In spite of who's bringing the facility here, it's much needed," said Gail Eluwa, chair of the N.C. Black Leadership Caucus, which promotes the empowerment of African-American and low-wealth people in the state. She said she would work with Variety to ensure it employs local workers. While North Carolina's population is 22 percent African-American, Pope has reported that African-Americans make up over 44 percent of the company's employees and over 37 percent of its managers.

But Rev. Johnson of the Raleigh-Wake Citizens Association told The News & Observer that he was concerned the store would offer only minimum-wage jobs. Indeed, workers at the company's stores complain of low wages and poor benefits. One person who worked for Variety Wholesalers full-time for more than five years as a cashier and department manager recently reviewed the experience at Glassdoor.com:

I loved the people I worked with that was the only perk really. You're required to work major holidays and don't get holiday pay. I had a few customers I really enjoyed seeing every week. … No employee discount, you have to be an employee for 2 years to get a stupid gift certificate at Christmas that you have to spend in store on their crappy merchandise. I worked there 6 years never made it to $8 an hour, you only get a raise when minimum wage goes up.

Another former Variety Wholesalers employee had this to say about the experience:

WOW...1.) no matter how long you work for the company (or how hard) chances are, you will never make over $8 (as a regular employee). 2.) There are not many advancement opportunities worth considering when you pair the additional workload & responsibities to the dimes & nickels they are willing to add to your pay. 3.) Due to what management blamed on payroll, my pay & my hours were always unstable. (Yet, they continued to hire people) 4.) Management selfishly expects you to put the company above all else, inspite of the insulting pay & the unstable hours they give to all part-time worker's. 4.) They usually don't offer full-TIME employment and regardless of your considerable amount of work experience, you will be started off being paid minimum wage. 5.) ABSOLUTELY NO employee discount, in addition to that YOU PAY for you work shirts. SAD.

In recent years, Variety has been the target of boycotts called by various groups over Pope's politics and the stores' business practices. In 2010, the North Carolina Democratic Party called for a boycott to protest what it called Pope's "corporate takeover" of elections, referring to his spending hundreds of thousands of dollars from Variety's corporate treasury on state politics. Then in 2012, the North Carolina Association of Educators called for a holiday boycott of Pope's stores over what they called his "anti-public education" policies.

And last year, the North Carolina NAACP and other groups launched "informational pickets" at Pope-owned stores to draw attention to the disconnect between the source of Pope's wealth and his political agenda, which they say hurts the very communities his stores serve. Pope and his network of think tanks and advocacy groups have worked to restrict voting in a way that disproportionately affects people of color, to reject Medicaid expansion and thus limit access to health care for the working poor, and to give wealthy interests greater power to influence elections.

Pope has defended himself by pointing out that his company "pays millions of dollars in payroll to our employees, and collect and remit to the state millions of dollars in income and sales taxes to finance our public schools and other public services," all while giving people "an opportunity to shop and buy great values in their neighborhood."

'We should not participate in our own oppression'

Among Pope's critics is Erin Dale, one of the leaders in the effort to establish the Fertile Ground multi-stakeholder food co-op in Southeast Raleigh. As Dale wrote in a recent post to her Facebook page:

We should not participate in our own oppression. No way, no how, any Negro who understands who Art Pope is should support his efforts to profit off the back of our folks in SE Raleigh and then use our money to pass policies that hurt our community.

While a co-op like Fertile Ground is a profit-making business, it operates on a dramatically different model than the type of capitalism pursued by Pope. Co-ops are democratically owned and controlled by their members, whereas corporations are owned by shareholders or, in the case of businesses like Variety Wholesalers, by private owners who exercise complete control over the company's operations and profits. Cooperatives also typically offer education and training to help stakeholders contribute effectively to the group's development. The Land O'Lakes dairy company, Sunkist citrus growers, and True Value hardware are well-known businesses that are cooperatives.

Cooperatives have a long history in African-American communities and played a critical role in the civil rights movement by giving blacks economic opportunity denied them by the white power structure. They include initiatives like the Freedom Quilting Bee in Alabama, a co-op formed by women sharecroppers in 1966 that made money selling quilts to build a sewing factory to make more quilts -- and to purchase land for farming so members who got kicked off white-owned land for registering to vote or taking part in other civil rights activities had land to work.

Jessica Gordon Nembhard, author of "Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice," recently told journalist Laura Flanders of GRITtv that this history remains widely unknown in part because it was too dangerous for participants to talk about due to the threat of both white supremacist violence and Red-baiting. But because the history is increasingly coming to light, Gordon Nembhard says, "the movement is moving again," as illustrated most vividly by Jackson Rising, a conference on new economies held in the Mississippi capital in May, inspired by the late mayor Chokwe Lumumba's goal of transforming the city through cooperative enterprise -- or what he called the "solidarity economy."

That the co-op movement would be moving in Southeast Raleigh makes historical sense, given the community's place on the leading edge of African-American progress. Southeast Raleigh is where Shaw University, the South's first African-American college, was formed after the Civil War, training tens of thousands of black teachers, doctors and lawyers. And it was at Shaw that famed civil rights leader Ella Baker organized a student meeting in 1960 that led to the foundation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, one of the largest and most important groups involved in the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

At the first public meeting of the Fertile Ground Food Co-op held in July, Dale reported that a feasibility study commissioned by the group had identified possible sites for the store. The top-ranked one was the same Kroger Pope had bought just a week earlier, she reported, but the co-op leadership continues to look into other possibilities. At the end of the meeting, dozens of community members -- black and white, men and women, younger and older -- lined up to pay $100 for founding memberships. The next day, Dale announced on the co-op's Facebook page that the organization had more than doubled its membership in one day.

"Looking forward to building a new economy with you," she wrote.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.