How Art Pope's money shaped UNC's toxic debate over Nikole Hannah-Jones

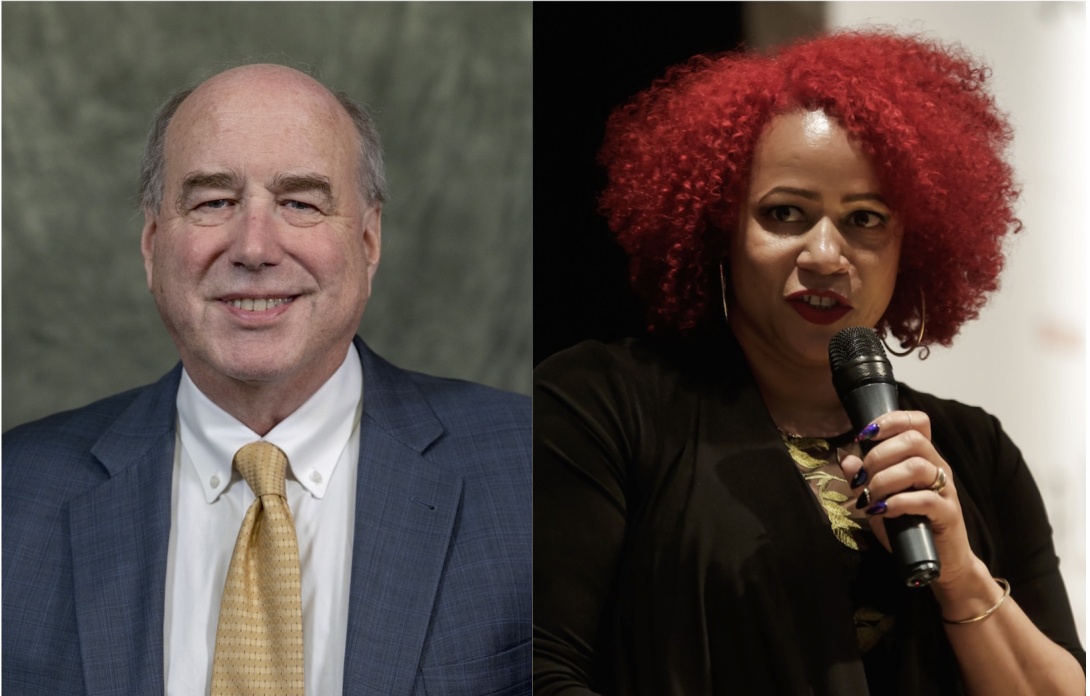

The conservative influence network founded and funded by millionaire North Carolina businessman, leading Republican donor, and UNC Board of Governors member Art Pope has long targeted the work of Nikole Hannah-Jones, an award-winning investigative journalist who focuses on racism. (Pope photo is from the UNC Board of Governors website; Hannah-Jones photo is by Alice Vergueiro/Abraji via Wikimedia Commons.)

(Correction: While the student member of the UNC Board of Governors is a non-voting member, the student member of the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees is a voting member.)

Now that award-winning New York Times journalist and 1619 Project visionary Nikole Hannah-Jones has decided against an offer to teach as a Knight chair at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Hussman School of Journalism and Media following a tenure battle with the school's Board of Trustees, observers — and Hannah-Jones herself — are still trying to understand what happened in a public university hiring process that's been secretive, confusing, and hurtful to many.

The school's Board of Trustees initially declined to act on Hannah-Jones' tenure application — already approved by the faculty — without public explanation. It reconsidered late last month after news coverage of the decision sparked widespread criticism and protests by faculty, students, alumni, and advocates for academic freedom; many of the protesters noted that the school's other Knight chairs were granted tenure. It's still unclear who on the board was involved in the initial decision and why it was made. The board reconsidered the tenure bid only after a formal request by newly elected Student Body President Lamar Richards, a non-voting ex officio member of the board.

"To this day, no one has ever explained to me why my vote did not occur in November or January, and no one has requested the additional information that a member of the Board of Trustees claimed he was seeking when they refused to take up my tenure," Hannah-Jones wrote in a statement about her decision, in which she called the last few weeks "very dark." "The university's leadership continues to be dishonest about what happened and patently refuses to acknowledge the truth, to offer any explanation, to own what they did and what they tried to do."

The Hussman faculty blasted the board's handling of the matter as "racist," writing in a statement: "We regret that the top echelons of leadership at UNC-Chapel Hill failed to follow established processes, did not conduct themselves professionally and transparently, and created a crisis that shamed our institution, all because of Ms. Hannah-Jones' honest accounting of America's racial history. It is understandable why Ms. Hannah-Jones would take her brilliance elsewhere."

Lurking behind the controversy over Hannah-Jones at UNC — and the wider controversy over the teaching of critical race theory, a scholarly approach to understanding institutionalized racism — is millionaire businessman Art Pope, a UNC-Chapel Hill alumnus and leading Republican donor who created and funds an influential network of conservative think tanks that have been at the forefront of debates around race and education in North Carolina. Pope's network has long promoted disinformation about climate science in the public policy debate, and it's now using bad-faith arguments to attack scholarship on race that conflicts with its conservative political agenda, with an eye to boosting GOP chances in next year's midterm elections.

But nowadays Pope is not just any businessman using his wealth to promote his ideas among state policy makers: Since last June he's been a full member of the UNC System's Board of Governors, appointed by the Republican legislature he helped elect. He serves on its Committee on Personnel and Tenure and the Committee on Audit, Risk Management, and Compliance. He's now among the two dozen people — overwhelmingly white Republican businessmen — responsible for overseeing the 17 schools in the UNC system, one of the nation's largest.

Pope told WRAL News he wasn't involved in the Hannah-Jones decision and didn't have "any firsthand knowledge" about the discussions over her tenure. But the advocacy network he funded played a critical role in shaping the debate over her work and potential hiring, and his spending has profoundly shaped the political landscape where it played out. Hannah-Jones herself pointed to Pope in her statement declining UNC's tenure offer, noting how his education-focused think tank "railed against the university for subverting the board's tenure denial." Contacted through his family foundation, Pope did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

Defending David Duke

After a childhood of attending camp near Raleigh run by the conservative Cato Institute, borrowing his dad's copies of Reason magazine, reading Ayn Rand, and attending the private Asheville School, which admitted its first Black students in 1967, Pope headed to UNC-Chapel Hill to study political science. He almost immediately got involved in racial politics at the school: As a freshman in 1975, Pope filed a complaint under the code of student conduct against Black Student Movement President Algenon Marbley because Marbley was part of a group of about 200 student protesters who shouted down Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke of Louisiana as he tried to deliver a speech on campus.

Pope's complaint charged Marbley with "willfully disrupting a normal operation or function of the University." In his defense, Marbley argued that it was "not a normal function" of the school to invite a speaker who advocates killing people because of their race. Marbley's attorney, D. Lester Diggs, called Pope's complaint "a decision to employ racialism rather than medication to relieve himself from the type of political indigestion incurred from the Duke event." After the student court acquitted Marbley, Pope penned a letter to the Daily Tar Heel defending his actions.

"I came to Carolina expecting the unbridled pursuit of knowledge," Pope wrote. "I thought I would have the right to decide for myself if what I learned was the truth or a lie. Unfortunately these past events have shown that I was mistaken." He again defended himself in a 2017 letter to the paper in response to a student's letter accusing him of racism over the incident, saying that — while he "vehemently disagree(d) with Duke and the KKK" — he believes they have a legitimate claim to First Amendment protections at campus-sponsored events.

The year after UNC's David Duke uproar, Pope became one of the co-founders of the North Carolina Libertarian Party — though as The New Yorker reported he left after a few meetings because attendees spoke seriously about Bigfoot. He graduated with honors from Chapel Hill in 1978 and earned his J.D. from Duke Law in 1981. He practiced with a Raleigh firm and then worked for the successful 1984 campaign of Republican Gov. James Martin, for whom he served as special counsel. Pope joined Variety Wholesalers, his family's discount retail chain, in 1986; two years later he was elected to the state House as a Republican from a Raleigh district and went on to serve several non-consecutive terms. He ran for lieutenant governor in 1992 and won the Republican primary but then lost to a Democrat, whose party then was still largely in control of state politics.

As Facing South was among the first to reveal in a 2010 investigative series, it was around this time that Pope began building a network of think tanks to promote his conservative worldview. To do so, he drew on the resources of the family's John William Pope Foundation, named for his father and funded by the family business, which sought out locations where at least 25% of the nearby population was Black with a median household income of $40,000 or less. In 1990, Pope launched the network's flagship think tank, the John Locke Foundation, to promote limited government and free enterprise.

The Pope network also includes an education policy think tank originally founded in 2003 as the John William Pope Center for Higher Education and now called the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal. It plays a leading role in pushing the Pope network's agenda for higher education, aiming to counter a perceived left-wing takeover of campuses. It advocates for a conservative and traditional curriculum and increasing the power of private donors in public university decision-making. James C. Moeser, who served as the chancellor of the UNC-Chapel Hill campus from 2000 to 2008, told The Chronicle of Higher Education several years ago that the Martin Center has "strongly influenced the direction of the Republican Party in the state. Most faculty are terrified of them."

Then there's Pope's Civitas Institute, a conservative policy group founded in 2005 that merged with the John Locke Foundation last year. Civitas is the group that infamously posted the mugshots of nonviolent Moral Monday protest arrestees in a bid to show they were not from North Carolina only to reveal that 98% were — a failed attempt to deploy the same "outside agitator" narrative wielded by Southern authorities against civil rights protesters in the 1960s.

Besides launching the conservative advocacy groups, Pope is also their primary bankroller. According to the most recent publicly available IRS filings and Pope Foundation grant announcements, the Pope family foundation provides about 70% of the John Locke Foundation's annual budget of over $3.6 million and about 77% of the Martin Center's annual $643,000 annual budget. And prior to its merger with the Locke Foundation, Civitas got almost all of its funding from Pope. Pope has poured well over $55 million into the network to date, building a state version of the conservative juggernaut Charles and David Koch constructed on a national level. The Pope and Koch networks have worked in tandem on matters like climate science denial, and Pope previously served as a director for the Kochs' Americans for Prosperity organization and has been a major funder of the Americans for Prosperity Foundation.

Pope's John Locke Foundation and Martin Center are also members of the State Policy Network (SPN), a national alliance of conservative think tanks. The Center for Media and Democracy describes SPN as "the tip of the spear of far-right, nationally funded policy agenda in the states that undergirds extremists in the Republican Party." SPN member groups, it says, "operate as the policy, communications, and litigation arm of the American Legislative Exchange Council," referring to the politically influential nonprofit that brings together conservative state lawmakers and corporate interests to promote pro-business legislation. According to NBC News, ALEC was among the conservative groups that held webinars last winter sounding the alarm about critical race theory.

While the Pope network is outspoken on racial matters, it suffers from a glaring lack of internal racial diversity. The John Locke Foundation's board of nine appears to be all white, as does its staff of 26. The Martin Center's board of 10 also appears to be all white, while its staff of eight appears to be all white except for a policy fellow who is of South Asian descent. (Facing South invited the Pope Foundation to correct these numbers if they were wrong but got no response.) And though Pope has worked to cultivate an image as a reasonable Republican, the boards of his organizations include U.S. Rep. Virginia Foxx, a North Carolina Republican who aided and abetted the U.S. Capitol insurrectionists by objecting to certification of the 2020 presidential election as part of a GOP disinformation campaign equating an increasingly diverse electorate with voter fraud, and Paul "Skip" Stam, a former state House member known for likening homosexuality to "pedophilia, masochism, and sadism."

Pope has exhibited hostility toward diversity efforts in other ways, too. In 2009, for example, he served as what one political ally called "the architect" of a successful plan — as well as one of its leading financiers — to oust the pro-desegregation public school board in Wake County where he lives. The Pope-backed board called for a return to "neighborhood schools," drawing scrutiny from federal civil rights investigators. Two years later, Wake County voters ousted Pope's candidates and elected a board that supported diversity initiatives.

Smearing critical race theory

The toxic debate over Hannah-Jones at a public school built by enslaved Black people has come amid a wider national campaign led by conservative political forces to squelch teaching of certain ideas embedded in her work — specifically, those they perceive to be related to critical race theory, an academic movement that began in the mid-1970s among Black legal scholars that examines how the social construction of race and institutionalized racism perpetuates a racial caste system that assigns people of color to the lowest tiers, while also recognizing how race intersects with other identities. The anti-critical race theory campaign is part of a longer conservative assault on higher education that can be traced back to the post-World War II Red Scare, which by 1963 led the North Carolina General Assembly to ban communists from speaking at UNC.

Last September, shortly after Fox News' Tucker Carlson show aired a segment sounding the alarm about critical race theory, former President Donald Trump issued an executive order banning diversity trainings for federal employees that discuss the idea. President Joe Biden reversed the order on his first day in office, but the censorious attacks on critical race theory exploded at the state level.

According to an Education Week analysis, proposals have been introduced in at least 26 states in the past year to restrict teaching of critical race theory. Legislatures in at six — Idaho, Iowa, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas — enacted critical race theory teaching bans while four others — Florida, Georgia, Montana, and Utah — have taken other state actions to ban it. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, widely considered a potential 2024 Republican presidential candidate, said it was necessary to ban critical race theory from public schools in order to serve students facts rather than "trying to indoctrinate them with ideology." In North Carolina, a bill to ban the teaching of critical race theory passed the state House in May and is now being considered in the Senate.

Pope's groups have long been critical of critical race theory, with the Martin Center railing against it as early as 2017 and referring to it repeatedly as "grievance studies." Along with the rest of the right, they later turned their attention to Hannah-Jones' 1619 Project, published by The New York Times Magazine in August 2019 in commemoration of the 400th anniversary of trafficked Africans landing on Virginia's shores — an effort "to reframe the country's history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of the United States' national narrative." In fact, the Pope network's first look at the 1619 Project and critical race theory — a November 2019 Civitas blog post by editor Ray Nothstine — was relatively balanced, raising concerns about critical race theory's inclusion in the Winston-Salem school curriculum but noting that "it may not be deserving of outright flame-throwing or bombastic opposition."

But last September, after conservative writer Christopher F. Rufo appeared on Tucker Carlson's Fox News show as part of the right's campaign to use CRT to attack anti-racism efforts, the Pope network's coverage of it and the 1619 Project exploded, as it did throughout conservative media. It also became uniformly and completely dismissive, relentlessly attacking the project over disagreements with historians while ignoring anyone who found value in its interpretation. Civitas' Nothstine got on message, now claiming that the 1619 Project propagates lies about America. From September through December 2020, during the height of the U.S. elections and at the same time Hussman School leadership was wooing Hannah-Jones out of public view, the Martin Center published at least seven items attacking critical race theory and/or the 1619 Project while the John Locke Foundation and Civitas produced a couple each. The goal of the anti-critical race theory effort, as Rufo described it on Twitter, is to "have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think 'critical race theory.'" Another major funder of anti-critical race theory efforts has been the Bradley Foundation, a Milwaukee-based conservative grant maker chaired by Pope.

Last November, amid a presidential election that served as a national referendum on race following a summer of racial justice protests, the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees was scheduled to take up the matter of Hannah-Jones' tenure, which had already been approved by the school's Promotion and Tenure Committee. "The day of the Trustees meeting, we waited for word, but heard nothing," Hannah-Jones would later recount in her statement on declining the school's tenure offer. "The next day, we learned that my tenure application had been pulled but received no explanation as to why. The same thing happened again in January. Both the university's Chancellor and its Provost refused to fully explain why my tenure package had failed twice to come to a vote or exactly what transpired."

Instead, in February 2021 Hannah-Jones signed a five-year contract to teach at UNC-Chapel Hill without tenure but said nothing about it publicly. The news about the hire broke in April. On May 10, the Martin Center published a blog post saying the hire "signals a degradation of journalistic standards," questioning how Hannah-Jones was hired without the trustees' approval, and calling on the Board of Governors to "amend system policies to require every faculty hire to be vetted by each school's board of trustees."

But Hannah-Jones noted in her statement that at the time the blog post was published the news had not been made public that she had been hired without the trustees' approval. "Even faculty at the journalism school were not aware that I had not been considered for tenure and would not learn this until some days later," Hannah-Jones said in her statement, raising more questions about the role of Pope's network. On May 19, the liberal publication NC Policy Watch broke the news about UNC backing down from offering her tenure.

The ensuing uproar revealed a couple of key players in the decision. One is Walter Hussman, millionaire publisher of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette and donor for whom UNC-Chapel Hill's journalism school is named. Emails obtained by The Assembly magazine show he lobbied school leaders against Hannah-Jones' hiring. That his concerns would be prioritized by the administration is something the Pope network has long advocated for as a proponent of "donor intent" — increasing the power of private donors to influence decision-making in higher education, or what it calls "steering a college in a more sensible direction with your grants." Pope himself is a major donor to UNC-Chapel Hill, with his family foundation contributing $10 million in 2018 for cancer research and other specific programs. (In 2004, however, faculty protested a plan by Pope to donate more than $10 million for a new "Studies in Western Civilization" program that they worried would try to promote a conservative agenda, ultimately leading him to withdraw it; a 2011 effort by Pope to establish a constitutional law center at North Carolina Central University, a historically Black school in the UNC system, was also scuttled by protests.)

The other key player is state Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger. Politics North Carolina, a website published by longtime Democratic political consultant Thomas Mills, traced responsibility for the Hannah-Jones decision to Berger and observed that his thinking on UNC has been "deeply influenced" by the Pope network. Pope has contributed over $39,000 to Berger's campaign. This week Berger called for legislation outlawing the teaching of critical race theory as well as a state constitutional amendment banning affirmative action.

As the controversy over critical race theory continues to rage at UNC and other institutions, experts in the field have pointed out that the conservative assault illustrates the field's basic tenets. Gary Peller, who teaches constitutional law at Georgetown University Law Center and is a contributor to and co-editor of "Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement," noted in an opinion piece for Politico that its opponents "are just proving our point for us."

GOP takes the reins

As with its efforts to discredit the science behind climate change, the Pope network's discussion of critical race theory, the 1619 Project, and Nikole Hannah-Jones has focused on supporting a political position, complicating facts be damned.

For example, the Martin Center has repeatedly cited Princeton history professor Sean Wilentz's criticisms of the 1619 Project in arguing why Hannah-Jones should not be granted tenure. It did so in blog posts by President Jenna Robinson and Director of Policy Analysis Jay Schalin. Wilentz was also a discussion point in a John Locke Foundation webinar on the Hannah-Jones controversy, which featured Peter Wood of the conservative National Association for Scholars and Matthew Spalding, a former employee of the conservative Heritage Foundation who directed President Trump's 1776 Commission, the right's response to the 1619 Project that was condemned by historians as an error-ridden hack job. Yet the Pope organizations have not reported that, while Wilentz has criticized aspects of the 1619 Project, he has also called her tenure denial "a travesty."

"The board has said little about the decision, but it would appear that political considerations drove them to take the extraordinary step of intervening in the university's hiring decision for an individual faculty position," Wilentz wrote in a May 24 letter to The Chronicle of Higher Education. "Such an action would be a gross violation of the principles that ought to guide the governance of modern American universities and a clear threat to academic freedom. Unfortunately, the temptation for political tampering with the operation of universities is growing not just in North Carolina but across the country."

Pope's political tampering at UNC and willingness to throw his money around have been well documented. As Jane Mayer reported in her 2011 New Yorker profile of Pope, he wanted a seat on the UNC system's Board of Governors as far back as 1995 when he was serving in the state House. But former House Speaker Richard Morgan (R) said Pope was repeatedly rejected by colleagues who "thought he was too big for his britches." Mayer wrote:

When Pope didn't get his way, Morgan claims in his memoir, he tried to pull rank among the Republicans by citing his family's money. Morgan writes that, at one point, Pope showed up in his office and "rapped a list down" on his desk with "every candidate and group he and his family had given money to." Morgan told me, "I think it was his effort to say, 'You owe me this.' It happened more than once."

Pope didn't give up, though — he played the long game. In 2010 he helped engineer the Republican takeover of the North Carolina legislature for the first time since Reconstruction as a key contributor to the REDMAP project, which sought GOP control of statehouses in advance of drawing new post-census election maps. Of the 22 legislative races targeted that year by Pope, his family, and their organizations, the Republicans won 18, putting both legislative chambers under GOP control. The new majority then drew voting maps that further locked in their power while pushing the body further to the right. According to reporting by ProPublica, Pope was in the room as a legal adviser when the maps were being drawn in 2011 and gave direct instructions to the technicians drawing them. The courts later ruled that the legislative and congressional maps drawn as part of this process were unconstitutional racial gerrymanders that disempowered communities of color; the courts also ruled them to be partisan gerrymanders.

The Republican legislature engineered by Pope — and its all-white caucuses — have sought to transform what used to be the Democratic-dominated UNC Board of Governors and UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees into Republican strongholds and place them under tighter control. For example, after Democrat Roy Cooper defeated Republican Gov. Pat McCrory in 2016, one of the legislature's first moves was to take away the governor's traditional power to appoint voting members of the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees; four are now chosen by the legislature and eight by the Board of Governors, with the student body president also serving as a non-voting member. In addition, state House leaders this year introduced legislation that would expand legislative influence over the Board of Governors by appointing two members of the state House and two members of the state Senate as non-voting members.

The Board of Governors has also sought greater control over the UNC system's presidents and programs. In 2015 — the same year it shut down UNC-Chapel Hill's Center on Poverty, Work, and Opportunity because leader Gene Nichol, a law professor at the school, harshly criticized legislative Republicans in newspaper columns — the Board forced out President Tom Ross because he was a Democrat. It then ran out his replacement, former George W. Bush associate Margaret Spellings, over her handling of protests that led to the tearing down of the "Silent Sam" Confederate monument on campus, which they regarded as not tough enough. The Board went on to secretly negotiate a $2.5 million settlement with the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) to give them possession of the statue and house it on campus, a highly controversial decision later overturned in court. The system's current president is Peter Hans, a UNC-Chapel Hill alumnus who previously worked as an advisor to Republican U.S. Sens. Lauch Faircloth, Elizabeth Dole, and Richard Burr. In 2017 the Board of Governors also barred the UNC Center for Civil Rights from engaging in litigation, and this year it opted against reappointing UNC law professor Eric Muller to the UNC Press Board of Governors. Muller said in a statement that he was given no explanation but that he "would hate to think it had something to do with my public commentary in recent years on matters of law, race, and history," including his criticism of the state law barring removal of Confederate monuments, the SCV settlement, and the moratorium on renaming UNC buildings bearing the names of white supremacists.

Pope personally got an opportunity to exercise significant institutional power over the UNC system during his stint as budget director for Gov. McCrory, a position he held from January 2013 to September 2014. Shortly after his appointment, Pope fired off what The Washington Post called "an unusual memo" to UNC leaders chiding them for submitting a budget proposal that ignored his office's instructions to limit expansion requests to no more than 2%. Hans defended the request but noted that Pope was "doing what taxpayers should expect him to do." Many observers saw the move as Pope using his new powers to carry out a longstanding personal agenda to cut the system's budget while at the same time using his own money to fund positions and programs and expand his influence over the curriculum.

Last June, Pope's long game ended in a big win as the legislature he helped put in place finally appointed him to his long-sought seat on the Board of Governors. He succeeded former state Sen. Bob Rucho, a Republican who was a leader in the effort to gerrymander the state's 2011 political maps. Many were appalled by the move. "You've got to be f***ing kidding me," tweeted Democratic state Sen. Sam Searcy in response to Pope's appointment. "This is an insult to the UNC system and what we get with a Republican majority bought and paid for by Art Pope."

No appetite for change

During the time Pope has amassed growing influence over the UNC system, its students, faculty, and staff of color report that conditions have deteriorated. In November 2020, for example, the system released preliminary findings from the work of its Racial Equity Task Force, established five months earlier. Not only was the system failing to meet benchmarks, as NC Policy Watch reported, but the results were worse than those from 2018. Of UNC-Chapel Hill's more than 4,000 total full-time faculty members as of fall 2020, only 226 were Black, and only 69 had tenure, according to a university report.

"There is a perceived lack of commitment in DEI [Diversity, Equity and Inclusion] from the UNC System leadership, as seen by students, faculty and staff," the report said. "Participants say they have seen and participated in a lot of listening efforts, and have not seen meaningful action. Participants are looking for new or improved processes and policies within the UNC System that address student, staff and faculty priorities."

The task force's final report was released this past January at a Board of Governors meeting — at the same time the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees was sitting on Hannah-Jones' tenure application. Task force members reported hearing from many students and employees of color who said they felt overwhelmed and unappreciated in the UNC system.

The handling of the Hannah-Jones affair has only further alienated people of color at the school. It's why Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery announced that she was leaving for Emory University in Atlanta, while Lisa Jones, a Black faculty recruit for the school's chemistry department, said it made her decide against accepting the job. And at last month's meeting of the Carolina Black Caucus, an alliance of UNC-Chapel Hill employees of African descent, 70% of the 30 people in attendance reported that they were considering leaving the school, and 60% said they were actively looking for other jobs. Jaci Field, co-chair of the group's advocacy committee, said Black people "feel generally undervalued at Carolina" and that the Hannah-Jones situation "really just brings the issue to the forefront."

Following the uproar over Hannah-Jones not getting tenure, UNC Chapel-Hill Student Body President Richards published an open letter in NC Policy Watch student inviting any student, staff member, or academic from a historically marginalized identity who might be exploring UNC to look elsewhere. "If you are considering graduate school, law school, medical school, or other professional programs at UNC, I challenge you to seek other options," he wrote. "While Carolina desperately needs your representation and cultural contributions, it will only bring you here to tokenize and exploit you. And to those that will attempt to misconstrue these words — my words — understand this: I love Carolina, yes, but I love my people and my community more."

This week brought new concerns about leadership at the school, with the faculty holding an emergency meeting to discuss fears that state politicians, trustees, and the UNC Board of Governors are considering removing current UNC-Chapel Hill Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz; Indy Week reported that among those rumored to be possible replacements are Clayton Somers, the former chief of staff for state House Speaker Tim Moore and a key figure in the negotiation of the scrapped settlement with SCV over the Confederate monument formerly on campus, and John Hood, a longtime Pope associate and president of the Pope family foundation. And there was a meeting of the school's new Board of Trustees, which with eight white men, two Black men, one Asian American man, one Black woman and one white woman is slightly more racially diverse than the last board of 10 white men, one Black man, one Black woman, and one white woman, though still not anywhere close to representative of a student body that is 40.5% non-white and 59% female. The trustees elected new leadership, and the new chair and vice chair — both returning members and white men — voted against granting tenure to Hannah-Jones.

Through all the furor over Hannah-Jones, Pope himself has remained silent on the matter. The Martin Center also went quiet on racial issues in the immediate aftermath of the UNC-Chapel Hill's Board of Trustees move to reconsider its tenure decision and Hannah-Jones' decision not to accept the offer. But Pope's flagship John Locke Foundation continued to vigorously press its case, publishing a recent story attacking critical race theory and an opinion piece by Michael Jacobs, a part-time UNC-Chapel Hill business professor, that pitted the quest for truth against social justice while calling for efforts to boost recruitment of what he considers "the single most under-represented minority among Tar Heel faculty": conservatives.

As for Hannah-Jones, she accepted another job as the inaugural Knight Chair in Race and Reporting at Howard University in Washington, D.C., a school founded in 1867 to educate formerly enslaved people and their descendants. She said the last straw that led her to reject UNC's offer was campus police shoving student protesters out of the room at the June meeting where trustees took up her tenure. At Howard she'll join fellow MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant winner Ta-Nehisi Coates in establishing the Center for Journalism and Democracy, which will train journalists capable of "accurately and urgently covering the perilous challenges of our democracy."

In her statement turning down tenure at UNC, Hannah-Jones called for its leaders to press for a change to the role of both the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees and the Board of Governors. "This requires a change to the way the boards are appointed so that they actually reflect the demographics of the state and the student body, rather than the whims of political power," Hannah-Jones said. But that's unlikely to happen any time soon: House Speaker Moore — who as a conservative undergraduate leader at Chapel Hill sought to defund the school's Black Student Movement and Gay and Lesbian Association — said there's "no appetite" for changing the appointment process. His campaign has received over $32,000 from Pope.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.